The Cold and Bloody Ground of Fredericksburg

Anatomy of a Debacle

For all the controversy surrounding the Battle of Antietam, Major General George McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, could at least say that he’d held the field against General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. The latter force was retreating back home after an indecisive mutual massacre in Maryland. Lee’s army was battered and McClellan still had more fresh troops in his reserves alone than Lee had walking. Lincoln was thus confident that his arrogant yet diffident top commander would seize the initiative by pursuing and destroying his Confederate foe.

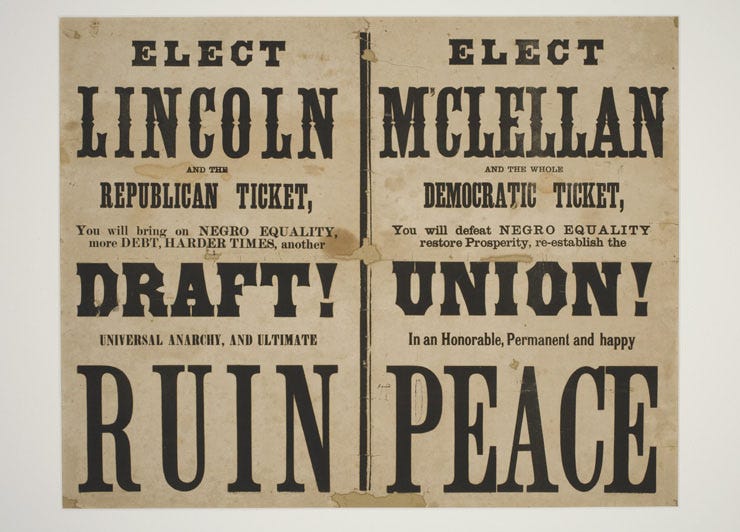

McClellan, however, thought he was the hero of the hour and proceeded to make a number of demands on the part of the Lincoln administration, namely for more men to counter the wholly imaginary 100,000 or so Rebels he persisted in believing he faced. When he received additional soldiers, his response was to sit where he was and demand still more. Fall was slipping away, with the cool, dry weather than was perfect for marching soon to be replaced by freezing misery. Ultimately, Lincoln lost patience for the last time and relieved McClellan in October of 1862. He would never hold a command again, though he would resurface as Lincoln’s Democrat rival for president in 1864.

The man who replaced McClellan was equally remarkable for equally unfortunate reasons. MG Ambrose Burnside, commander of the IX Corps of the Army of the Potomac, was Lincoln’s second choice without there really being a first. The Union Army in the Virginia theater was still packed with diehard McClellan loyalists; most of his critics had been packed off after their ringleader, MG John Pope, was exiled to fight Indians after the Union disaster at Second Bull Run. But even those who weren’t Little Mac’s creatures had little to offer, mostly consisting of superannuated lifers or peacocking politicians. There was certainly talent in the Army of the Potomac, but it was still mostly hidden in the middle ranks, the fires of war having not yet burned away all the dross.

Burnside had been a soldier for most of his life. Born in Indiana in 1824, he grew up on a farm, losing his mother at a young age but otherwise enjoying a typical rural life of the period. A West Point graduate of the Class of 1847 (the other notables that year being John Gibbon of the Union Army and A. P. Hill of the Confederate), he was firmly in the middle academically and made his way into the artillery rather than the Corps of Engineers that was the peacetime army’s elite. He missed action in the Mexican War, but did serve in the west- under Braxton Bragg of all people- managing to get an arrow through the neck fighting the Apache in the New Mexico Territory.

There was always something of the loser about Burnside. This was unfortunate, because by all accounts he was a genuinely brave, kind, intelligent, and hardworking man who always sought to better himself. But things never seemed to work out for him, sometimes comically, sometimes tragically. His first marriage ended before it started, with his bride-to-be actually dumping him at the altar. The woman in question, Charlotte Moon, would later go on to be one of the Confederacy’s most effective spies; Burnside later had to arrest her at one point in the war in a no doubt uncomfortable episode. While stationed in Rhode Island he tried marriage again, this time to a woman named Mary Richmond Bishop. At least that worked out for him; the union was a long and happy one, though childless.

Burnside was technically proficient and had an engineer’s imagination, and seeing the need for a good, breech-loading carbine, resigned his go-nowhere military career to create and market one. The design of the Burnside carbine was excellent, and he borrowed money to build a factory in Rhode Island to produce it, having received a large government contract. Things were going great- right up until a rival bribed the Secretary of War to cancel the deal. Partly in response, he ran for Congress, and lost in a landslide. Then the factory burned down. Bankrupt, he had to sell his patents and look for a job.

His new career was in the railroad industry, where he met two men who would greatly shape his future. His boss was none other than George McClellan, then vice-president and chief engineer of the Illinois Central Railroad. And of course, everyone who worked in that field in that state was well-acquainted with the leading industry lawyer-cum-politician, Abraham Lincoln. He was friendly with both- he always made friends easily- and both would smooth his way to high command when the war came in 1861.

Burnside was at first commissioned a colonel, but promotions came quickly to anyone with formal military training, and he was a brigadier general before his first summer in the Union Army was over. McClellan, fairly assessing his friend’s abilities, arranged for him to have a small independent command leading an amphibious attack on North Carolina. It was supposed to be a sideshow to the main events in Virginia, but Burnside actually acquitted himself extremely well, and what came to be known as the Burnside Campaign essentially locked down the North Carolina coast for the remainder of the war.

This success resulted in some overly-rosy evaluations of Burnside’s aptitude. He was promoted again, to major general, and given command of the IX Corps of the Army of the Potomac. But this was intended to be a stepping stone. Behind the scenes, the Lincoln administration was seeking out aggressive commanders to replace the obstreperous McClellan, and Burnside’s victory in North Carolina put him on the same tier as John Pope, victor in the West. He was offered command of the Army of the Potomac before Second Bull Run, and then again after; both times he declined. He was loyal to McClellan but more than that, he- unlike most of his preening peers- was humble and realistic about his talents.

He had much to be humble about. His performance at Antietam left a lot to be desired, with his inability to turn a Confederate flank that was hanging by a thread before enemy reinforcements could arrive and rout him in turn. Despite this, the Team of Rivals running the war, looking at who they had to work with, could only come up with two options to succeed McClellan once it was clear he was to be removed. One was Burnside; the other was MG Joseph Hooker.

Hooker was by far the better commander of the two, an aggressive and talented leader who’d led the brunt of the assault against the Confederate left at Antietam until he’d been shot through the foot and removed from the field. But Hooker had personal issues. He was a drinker and a partier, but worse was his penchant for conspicuous insubordination and political scheming. Burnside wasn’t exactly averse to the latter, but his evident modesty and willingness to tow the administration’s line made him their preferred choice. They offered him the job a third time.

Burnside wanted to decline again. He knew he wasn’t really even up to running a corps. But, for reasons that are obscure, he really hated Hooker, and felt that he would lead the Army of the Potomac to disaster. As events would later show, he wasn’t wrong. But when the President made it clear that McClellan was gone no matter what and Hooker would get the job if he didn’t take it, Burnside felt like he had no choice. He would square up and face the challenge head on.

Again, to be fair to Burnside, in many ways the administration set him up for failure. To begin with was the issue of his rank. Burnside’s elevation to higher command did not come with a promotion; he would still be a major general, as McClellan had been. This was the highest legal rank authorized by the Union Army at the time. MGs commanded divisions, but they also commanded corps and entire armies. And even though seniority was established by date of rank and billet, his lack of clear superiority over others made it harder for him to command the respect he needed. By comparison, Lee was a full (four star) general, one of six authorized by the Confederate Congress, and his corps commanders in the Army of Northern Virginia, James Longstreet and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, were both lieutenant generals. The Union would remain parsimonious with rank throughout the war; U. S. Grant was only grudgingly made an LTG when he became commander of all Union forces, and only given a fourth star after the war.

Then there was the related issue that the Army of the Potomac was still a snake pit of intrigue, with many McClellan loyalists resentful of Burnside’s rise, many (including Hooker) contemptuous of his abilities, and others who were simply overaged or incompetent. Even after the fiascos of the Valley Campaign, the Seven Days, Second Bull Run, and Antietam, there was still a lot of dead wood at the top that needed pruning. Sadly, it would be the lower ranks who would mostly suffer for that.

But ironically enough, Burnside’s biggest problem was supposed to be his greatest advantage- the sheer size of the Army of the Potomac. McClellan’s year and a half of ceaseless carping had netted him over 110,000 men, a force bigger than had ever been seen in North America, and the Army of the Potomac was only one of several Union commands. All those men had to be fed, clothed, housed, equipped, trained, and most importantly organized and led. Procedures for training staff officers were still ad hoc as the American military academies of the day still focused primarily on training engineers. Burnside didn’t have a lot of people he could trust in any case. A man like McClellan- who for all his faults was a superb administrator- could handle a challenge like that, at least when not in actual battle. Burnside was far out of his depth.

He attempted to solve his enormous command and control problems by creating a new level of organization above the corps level but below the field army- the grand division. Each of these would consist of 2-3 corps, operating under Burnside’s overall command. Burnside had more-or-less stumbled upon the concept that would later be called an army group, but characteristically, he couldn’t make it work. However he arranged it, his force was still led by a bunch of people of the same rank but with wildly different levels of responsibility, and while a stronger personality might still have made his will felt through loyal subordinates, Burnside had neither force of personality nor the respect of his commanders.

Burnside’s overall strategic goal was essentially McClellan’s- to take Richmond, the Confederate capital, which in theory would lead the South to surrender and set the stage for negotiations that would see the rebellious states folded back into a normal relationship with the Union. He proposed to do this by basically faking Lee out; he would trick him into thinking Union forces were moving west, when they would actually be marching very quickly directly south, across the Rappahannock river to Fredericksburg, and then speedily on to Richmond before Lee could catch up. Lincoln had other ideas; he wanted Lee’s army destroyed, correctly realizing that the Rebels would keep fighting as long as there were men able to fight. Burnside’s plan also relied quite heavily on Lee being far less clever and mobile than Burnside, which- to say the least- was doubtful. Nevertheless, Lincoln acquiesced to Burnside’s strategy, hoping that when Lee finally did catch up to Burnside, the latter’s numbers and resources would be a decisive enough advantage that the Army of Northern Virginia would be destroyed in any case. They were not hopes he held very strongly.

Burnside set his enormous force into motion on November 15th, marching to the north bank of the Rappahannock in two days, where he assumed he would find the pontoon bridging equipment he would need to move his whole force across the river to Fredericksburg. It wasn’t there. Due to characteristic bureaucratic sloth and confusion, the Corps of Engineers hadn’t been able to find enough horses to move everything. Yet again, his inability to pull rank had cost him. Burnside had a choice; he could move his forces across piecemeal or wait for the boat-bridges he needed to go over all at once. Fearing that Lee would show up and defeat his force in detail, he opted for caution, even as his more astute commanders pointed out that the hills on the far side of Fredericksburg, Marye’s Heights, were unoccupied and that even a small force could hold out there against Lee.

Lee had actually assumed Burnside would move faster than he did, and in response to Burnside’s advance had moved his own army still further south, thinking that Burnside would take Fredericksburg before he could get there. When days passed without that happening, however, he marched north and placed part of his force, Longstreet’s I Corps, on those same heights outside the city that Burnside had failed to take control of previously. His II Corps, under Jackson, he dispatched further south, to the next most defensible position, Prospect Hill. His line extended some seven miles. In both places, the Confederates spent the better part of ten days fortifying and sighting in their artillery.

Lee’s position was so strong that he figured Burnside wouldn’t attack him, expecting instead that the Union commander would move along the river to a more suitable place to cross. This didn’t concern him; his army was lighter and more mobile, able to maneuver into position quickly unlike the ponderous Yankees. He would have preferred to attack Burnside where he was, but the Union control of the ridge north and east of the city, Stafford Heights, meant that he would be at a severe disadvantage if he did so- better to wait for the Yankees to move and pounce on them at some unaware moment. His whole force, some 70,000 men, were gathered here in anticipation of such a maneuver. But while Lee was working out what he would do when Burnside pulled out, Burnside did the most Burnside thing possible and attacked at the exact moment when every likely chance of success was gone.

He’d finally managed to force a crossing into Fredericksburg on the 11th, his men compelled to assemble the late-arriving pontoon bridges under withering sharpshooter fire from BG William Barksdale’s Mississippians. The Union response was to shell the city from Stafford Heights, sending the civilian population running for safety. When the Union soldiers finally secured the bridgehead, they went wild, proceeding to loot and burn the city, their lack of discipline saying much about the quality of the officers who led them. Lee was incensed, as were the Confederates as a whole, but such destruction was a harbinger of what was to come in the war.

He’d taken the town, but now it remained to fight the Rebels on the outskirts. Burnside’s plan for the 13th, it seems, was for his Left Grand Division, under MG William Franklin, supported by his Center Grand Division under Hooker, to take Prospect Hill, while his Right Grand Division, commanded by Edwin Sumner, assaulted Marye’s Heights. The attack on the heights was probably intended to pin down Longstreet while Jackson was driven off the hill, which would then allow Franklin and Hooker to flank Longstreet, forcing the Confederates to retreat or be destroyed. I say ‘seems’ and ‘probably’ because Burnside never made his precise tactical goals clear to anyone, least of all his subordinates. Franklin was told to send “at least a division” to take Prospect Hill, rather than being explicitly ordered to conquer it with all available resources (he had six divisions organized into two corps not counting Hooker’s men, against Jackson’s single corps of four divisions). Franklin would end up sending a single division with another in support. That the taking of Prospect Hill was so important and yet handled so fecklessly by Burnside demonstrates yet again how over his head he was, a lesson Jackson would drive home in characteristically gory fashion.

The battle began around 10:30 as the fog cleared from the open field in front of Prospect Hill to reveal the division of MG George Meade advancing on Jackson’s position, supported by BG John Gibbon’s division. It went as well as could be expected with two divisions attacking the enemy’s three present, the latter fortified and well-prepared. Blasted by rifle and cannon fire, Meade briefly withdrew, then came on again around 1:00. This time, his lead brigade, desperate to escape the destruction, stumbled into a section of line under the control of MG A. P . Hill’s division, but which Hill had left unguarded under the assumption that it was too rough and swampy to penetrate. Hill was quite wrong. The Yankees found their way through and began attacking the outwards from the gap, blasting the Rebels in the flanks they’d created in their midst.

This might have been where the Union pulled victory from the jaws of defeat, but it was not to be. Gibbon didn’t support Meade and Franklin didn’t support either of them, and despite initial success Meade’s men were quickly out of ammo and exhausted. They soon discovered that the wily Jackson had actually anticipated this possibility and had staged the division of Jubal Early a half-mile back. Those men now came Rebel-Yelling into battle, driving the Yankees from their point of advance back out into the open field and back under Jackson’s cannons. By now the battle had been raging all afternoon. Franklin declined to attack again, claiming to Burnside that all of his men had been engaged already. This wasn’t true- he was either lying or unaware of that fact, either option speaking to his timidity and incompetence. The tall grass in the field before the hill caught fire, burning alive the wounded men left lying there. As the winter sun set on the rising flames and screaming fallen, Jackson held his hand aloft in thankful prayer, as was his custom.

Jackson took around 3,500 casualties to Franklin’s 5,000- horrible numbers, but a butcher’s bill that would seem cheap compared to the horrors unfolding a few miles to the north. Unaware that Franklin’s half-hearted assault on Prospect Hill was failing, Sumner had been launching waves of attacks against Marye’s Heights since 11:00 am. This involved marching out of Fredericksburg across nearly 600 yards of open ground, punctuated by buildings and fences and other obstacles that would make it difficult to keep lines of men together. But worst of all, right in the middle of the field was a canal that could only be crossed by three small bridges, meaning that the whole assault force would be bottlenecked there, a prospect not lost on Confederate cannoneers. LTC Edward Porter Alexander, Longstreet’s artillery commander, famously remarked to him of the situation, “General, we cover that ground now so well that we will comb it as with a fine-tooth comb. A chicken could not live on that field when we open on it.”

Had Sumner thrown caution to the wind and launched a full attack with his entire force in columns moving at double time, not stopping to fire, it’s possible that despite taking huge casualties they might have taken the heights through sheer mass. After all, Jackson was tied down with Franklin, and Sumner still heavily outnumbered Longstreet. But instead, due to poor organization and unclear orders, they came forward a brigade at a time, each launched in a frontal assault against a superbly fortified enemy, many of whom were firing from behind an impregnable stone wall. They were mowed down by Confederate rifle and artillery fire and none got closer than forty yards from their enemy.

The Stone Wall still stands. Note the ridge behind it, from which another line of Confederates would have been firing.

In the midst of this Burnside ordered Hooker forward- he’d originally been tasked with supporting Franklin, but now he was to be added to Sumner’s attack. Hooker did what no Union general before him had bothered to do, making a personal reconnaissance of the front. What he saw appalled him and he strongly advised Burnside to call off the offensive. Burnside, hitherto timid and cautious, chose this moment to stand his ground- the attacks would continue. Hooker’s men were fed into the slaughter as well. All told, there were fourteen separate attacks, each involving a brigade at a time, and each one took between 25-50% casualties. The final waves found their pantlegs clutched by the wounded of the previous advances, the fallen begging their comrades to turn around before they suffered a similar fate. Lee famously commented on the scene: “it is well that war is so terrible, lest we should become too fond of it.”

Burnside, even after a day of appalling slaughter, refused to concede defeat, which meant there would be no formal truce for medics to gather the wounded. Both sides spent the night of the 13th going into the 14th listening to the anguished screams and groans of freezing, dying men. By the morning of the 14th, it was more than one Rebel could bear. Richard Kirkland, of the 2nd South Carolina Infantry, asked his commander, BG Joseph Kershaw, for permission to give water to the wounded Yankees. Kershaw noted that he had no authority to proclaim a truce, meaning that Kirkland could expect to be under fire if he went out, and that if the Union soldiers fired, he would respond, leaving him unarmed in the middle of an exchange. Kirkland went anyway, gathering canteens from his comrades before going over the wall to help his enemies, who, realizing what he was doing, declined to shoot at him.

Much ink has been spilled attempting to debunk the story of the Angel of Marye’s Heights, but careful historical investigation has demonstrated the basic truth of the narrative.

But the Battle of Fredericksburg was over whether Burnside wanted it or not. The Union suffered over 12,600 casualties, with an appalling 1,200+ dead, more than double the Confederates- this despite Burnside outnumbering Lee by close to 40%. He’d fed his huge army into battle in destroyable-sized chunks and basically defeated himself in detail. The attack on Prospect Hill, despite being key to the whole plan, was grossly mismanaged, and the assault on Mayre’s Heights had all the effectiveness of trying to destroy a brick wall by hurling eggs at it. It was as though someone had handed a greatsword to a toddler- a potent weapon placed in the hands of someone unable to use it, and quite likely to injure himself trying.

Burnside- not without justification- blamed his subordinates. They in turn, with even more justification, blamed him. Ultimately, the Lincoln administration as a whole was at fault: they’d promoted a man who’d told them bluntly that he wasn’t up to the job on multiple occasions on the hope that resources would suffice in lieu of leadership. Burnside was relieved shortly after, but his career as a commander wasn’t over- there were other disasters ahead. Hooker ended up with the job in the end despite Burnside’s efforts to prevent it, and just as Burnside had predicted, he led the Army of the Potomac to disaster at Chancellorsville, after which Hooker was in turn removed and replaced by Meade, who, with new overall commander of the army U. S. Grant looking over his shoulder, kept his job until the end of the war.

Oddly, Burnside has been respectfully- if not fondly- remembered by his country despite his many failures. After the war he returned to civilian life, where he served three terms as the governor of Rhode Island, founded the National Rifle Association, and was elected to the Senate, holding his seat until his death in 1881. There are statues of him, towns named after him even. Perhaps people sensed that despite the disasters he’d authored he really did mean well, and were inclined to be sympathetic, especially given that he was hardly the only Union commander with a debacle to his name.

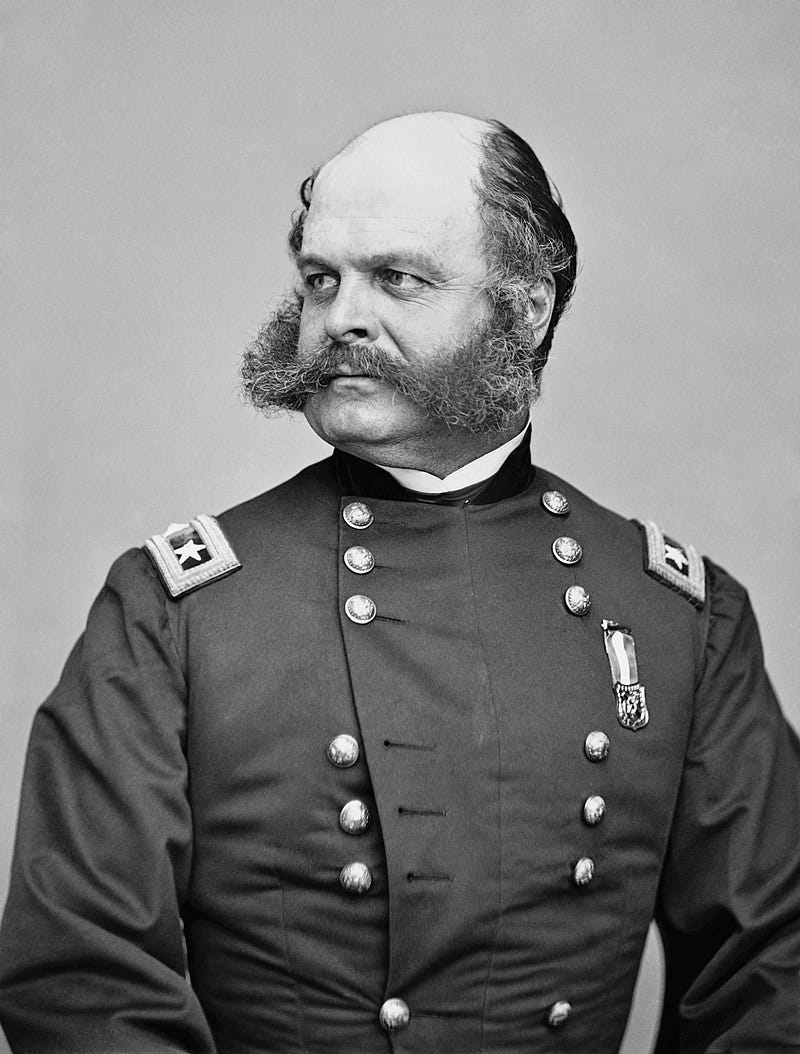

Perhaps still more oddly, his name became attached to a style of facial hair that became wildly popular around that time. He didn’t invent it, but the idea of fusing the hair in front of the ears to one’s mustache, sans beard, came to be known as sideburns, in a play on his name. And while historians rightly scorn his military ability, no one can argue that his hairstyling wasn’t top-notch. See for yourself; it’s so cool you hardly notice he’s bald.

Steal. This. Look.

Lincoln's agonizing search for a candidate competent to lead the Union army is miserably punctuated by failure after failure. You tell the story so well! I just finished Akinson's An Army at Dawn, about the WW2 Africa campaign, and a similar early string of failed generals is, for awhile, a plague on the ultimate success of the Allies. This was a great piece, thank you!

Sad that war is generally the tale of young men dying for the hubris and incompetence of old men. Some things don't change.