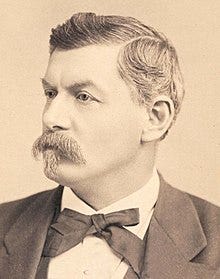

On this day in American history, September 19th, 1862, nothing happened. This is, however, quite significant in that a lot of things should have been happening. Major General George Brinton McClellan should have been aggressively pursuing the shattered remains of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, which the commander of the Union Army of the Potomac should have destroyed days earlier when he had the means and opportunity to do so. Instead, he licked his own wounds while sitting in place, content to allow his foe to march back to Virginia at a leisurely and unthreatened pace.

McClellan’s signal lack of aggression at this point would result in President Lincoln finally ending the general’s storied and controversial military career. Never had there been a beleaguered staff officer who’d done more and a commander with more promise who’d delivered less, a brilliant and talented man of great personal courage undone by his inner demons- his envy, his malicious paranoia, and above all his maniacal pride that made him, paradoxically, terrified of risks that might reveal some flaw in his ability. McClellan is in many ways a tragic figure in the sense the Greeks would have recognized, but it wouldn’t do to dwell on his own comeuppance for his hubris. After all, he emerged from his battles largely unscathed, returned to a very prosperous civilian life as a corporate executive and politician, and died whole and in his bed after a long life.

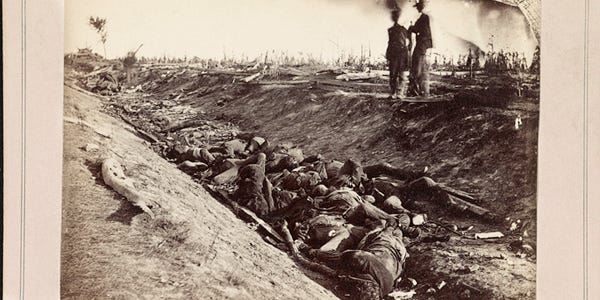

The same could not be generally said of those who fought under him- or against him. The Battle of Antietam (known as Sharpsburg in the South) was the single bloodiest day in American history, a 12-hour massacre visited by two groups of Americans upon one another that resulted in over 22,000 casualties, including over 3,600 dead. It was the culmination of a campaign by Lee to bring the Civil War home to the people of the North, to win a decisive battle there that would perhaps lead to foreign recognition of his Confederate government, and end the conflict with Southern Independence. One reads very often of the inevitability of Southern defeat, that various Union advantages made the North’s victory a foregone conclusion. A close examination of the battle can only put that supposition to the lie and demonstrate that it was not guns and butter but a willingness to kill and be killed that told on that day and in the larger conflict. The war could very much have gone either way at many points, and owed its outcome to equal parts spirit and fortune, and of course, ultimately, to the will of God. And in the end, for all the death that day, the ultimate significance of the battle would not be military, but ideological, a victory of meaning that remains the animating spirit of the memory of the Civil War in America.

Lee was riding high that autumn, as was the Army of Northern Virginia. He was fresh from a smashing victory at Second Manassas, having utterly routed Union commander John Pope despite the latter outnumbering him and having had the opportunity to defeat his force in detail. Lincoln had set up the Republican Pope as a foil to the Democrat McClellan, but now the former was exiled to the frontier while the latter inherited his forces to add to his own. Lee was not especially concerned at the return of McClellan to general command of Union forces in the Virginia theater, as Lee knew his rival well and counted on him being cautious and indecisive. This would be helpful because Lee intended something quite audacious and fully in keeping with his own character, an invasion of Maryland and a decisive battle on Union soil. He would march north, threaten Washington, bait McClellan into attacking him on favorable terms, and crush him. His veteran army, possessed of high morale if not high levels of materiel, was fully capable of achieving this.

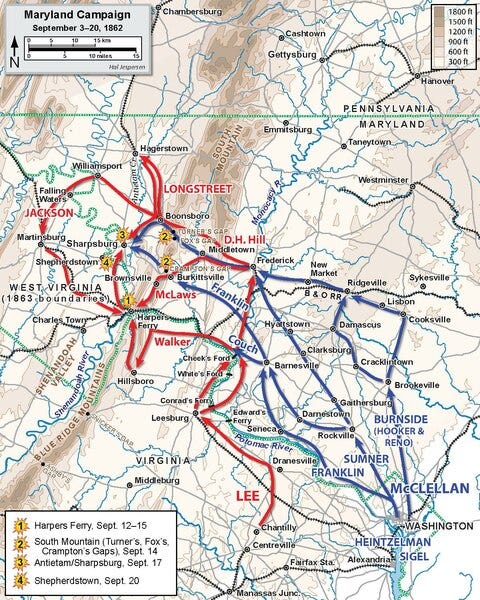

The plan was simply to roll right past the dawdling McClellan and march into western Maryland. Lee’s forces would be divided into several columns. The first, under Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, would take the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, securing his flank and taking much-needed supplies. The second, under the command of James Longstreet, would go further north to secure Boonsboro in Maryland and clear the way for the campaign to continue. Other smaller commands would support the main columns. Lee would retain a force operating slightly to the east of his subordinates. Lee was taking a risk in dividing his army, but he believed that McClellan would be slow to grasp his intentions and hindered in any case by his instinctive caution.

Normally, this would have been a good prediction, and one can envision Lee, even with all of the Confederacy’s disadvantages, maneuvering McClellan into the same sort of trap he’d laid for Pope, destroying his army in Maryland or Pennsylvania, and setting the stage for some sort of political solution to the war favorable to the South. But it was not to be, and for a very strange circumstance. On September 13th, a corporal in the 27th Indiana Volunteers, who had been alerted to the presence of the Confederate rear guard under MG D. H. Hill and were marching in pursuit, found an envelope with some cigars wrapped in paper at an abandoned Confederate campsite. The paper was a copy of Lee’s “Special Order 191,” which detailed all of Lee’s plans for his various subordinates. The document quickly made its way up the chain of command and McClellan found himself, quite by accident, in full possession of his enemy’s entire strategy, right down to where they would be and when they would be there.

It is unclear the extent to which Lee was aware that McClellan knew what he was up to, but he did quickly realize that the Union general was suddenly moving towards him with very uncharacteristic haste. This premature aggressiveness was obviously bad, as Lee was in no position yet to fight on ground of his that would advantage him, and worse, McClellan was potentially poised to defeat his army in detail. With his usual decisiveness Lee quickly adapted to the fact that his divided forces now seemed to be imperiled. He sent word recalling them all together, but much would depend in the short term on D. H. Hill’s defense of the three South Mountain Gaps, through which McClellan’s forces would have to march to get to everyone else. Hill’s spirited fight there on the 14th would be a defeat, but it bought Lee the time he needed, and gave Jackson time to force the surrender of Union forces at Harper’s Ferry that might otherwise be sent against them- 11,000 men, the largest Union capitulation of the war. All of his dispersed generals and their commands would coalesce near the town of Sharpsburg near Antietam Creek, a branch of the Potomac. Arranged on a low ridge with his back to that river Lee’s position was favorable but not especially strong, and he would need all of his legendary tactical ability if his men were to survive the coming onslaught.

They did have one extraneous factor in their favor. While Special Order 191 specified who was to go where, it said nothing about how many men each commander had. This omission worried McClellan, and whenever he grew so concerned, he tended to wildly overestimate the odds against him. Lee had around 18,000 men present when battle was joined on the 17th (though units would be coming in from Harper’s Ferry all day, giving him a total of perhaps 35,000 throughout) and McClellan had close to 80,000 by the end. But the latter supposed that Lee had somewhere around 100,000, and feared that Lee, despite appearances, was not actually in a desperate fight for survival, but rather laying a spiderlike trap such as had ensnared his rival Pope. This completely erroneous misjudgment would color the course of the whole battle.

McClellan’s plan involved a simultaneous assault from with four of his six available infantry corps. Two would initially assault from the north with one attacking from the south as a diversion. The other corps would serve as a reserve for the main attack, and the two remaining corps not initially deployed could be thrown in if the opportunity presented itself. But true to form McClellan did not give an overall plan beyond that, simply ordering each corps commander where to go without giving anyone a sense of his comprehensive operational intentions. His unwillingness to commit to an army-wide set of orders may have been due to his not wishing to attract blame if things went wrong while retaining the prospect of taking credit for his overall scheme succeeding. And there was no reason to think it wouldn’t; the basic idea was sound and fairly orthodox, what most generals would have done in his place.

The trouble was that the terrain over which the battle would be fought extended for nearly five miles and coordinating such an attack would require close supervision from a well-informed commander, able to issue orders rapidly to his subordinates. McClellan, however, chose to situate himself in a fixed position a mile back from the action in a manner that still attracts controversy today. Moreover, the logic of the Union disposition, as well as some skirmishing on the 16th, gave Lee a pretty certain idea of from what direction the main assault would come, and he would be able to take advantage of interior lines to maximize the effectiveness of his numbers and defensive posture. Making a textbook assault amounted to making a predictable assault, and Lee took full advantage of McClellan’s lack of imagination.

The fighting proper began at 5:30 am on the morning of the 17th. MG Joseph Hooker, leader of the I Corps, probably McClellan’s most talented and aggressive combat commander, launched the three divisions under his command, close to 9,000 men in all, south parallel to the Hagerstown Turnpike and the East Woods. There they ran into the forward elements of the command of Jackson, strongly dug in. An artillery duel commenced, followed by a general assault, a good proportion of it hand-to-hand between men literally colliding at short range. It must be noted that much of the fighting in the northern section of the battlefield took place in either one of several small forests or an area known as Miller’s Cornfield, usually simply called the Cornfield. In all of these areas visibility and the mobility of large units was greatly curtailed, especially after the noise and smoke of battle commenced, and much of the carnage that occurred was the result of confusion that would disproportionately affect the attackers who had to move in it. The Cornfield would change hands fifteen times over the course of the fighting, and by the end men would be tripping over the dead and wounded of previous exchanges in a grim and deadly maze.

The trail through Miller’s Cornfield today. Note that when the battle began it would have looked much like this, with man-high dry cornstalks reducing visibility severely.

Despite appalling slaughter Union numbers, experience, and courage began to tell, and the Confederates were slowly pushed back. Hooker’s goal was a piece of high ground made conspicuous by the simple clapboard church atop it, the place of worship for a local community of German Baptists, known to history as Dunker Church. But fate would intervene for the Confederates for the first of two times that day. Lafayette McLaws and Richard Anderson’s divisions both arrived on the battlefield from Harper’s Ferry at that moment, and they were thrown into the fray by Jackson alongside several others, including the division of MG John Bell Hood-commanding what were arguably the shock troops of the Army of Northern Virginia- which spearheaded the counterattack. They drove the Union I Corps back across the Cornfield, taking their own appalling losses in turn (Hood lost more than 60% of his men) as they were blasted back out of it.

Dunker Church shortly after the battle.

Hooker was now joined by the XII Corps under MG Joseph K. Mansfield. Had they attacked together earlier they probably would have swept the field already, but that order never came from McClellan. Now though Hooker arranged for another assault, this time with Mansfield on his left flank, coming in at the same time against the Rebels in the woods. Mansfield was an army lifer with 40 years of service, but he’d never commanded a unit in combat larger than a battalion and as it happened the XII Corps was comprised of a plurality of green troops themselves not used to being commanded. Mansfield thought the solution was to order his men into a tight formation to keep everyone from spreading out and becoming disconnected, perhaps fleeing under fire. Unfortunately he quickly discovered that this arrangement of his troops amounted to a force multiplier for deadly Confederate artillery, and the XII was torn to shreds. Mansfield took a bullet to the chest and was taken away to die in a field hospital. The attack in the north didn’t stop however. MG George Greene, commander of the XII Corps 2nd Division, managed to smash his way through the Rebels in the East Woods and on through to Dunker Church, but was unable to clear the West Woods, from which the Confederates launched counterattacks. To capitalize on this, MG Edward Sumner of II Corps sent two of his divisions-under MGs William French and John Sedgwick- into battle.

Hooker, by now fully comprehending the situation, would have been perfectly placed to coordinate a massive new attack had he not been shot through the foot and taken from the battlefield. Instead, the Union effort proceeded in the same piecemeal way, or rather worse, as the unimaginative and elderly Sumner, fresh on the scene, decided to accompany Sedgwick’s division in the interest of micromanaging and ordered the men into a tight series of lines reminiscent of the formation that had gotten so much of the XII destroyed an hour or so earlier. In addition, he lost contact with French to his left, who basically wandered off, and Sumner and Sedgwick’s poorly organized advance was surrounded on three sides and stopped cold in a hail of fire.

The fighting in the north died down around 9:30 am as the off-course French kicked off a fight against MG James Longstreet’s command in the center. This section of the Confederate line was undermanned from having its forces sent north all morning, but a sunken road on a slight ridge formed a natural trenchworks that made the position deadly even occupied by outnumbered men. French came on, followed by others, and though collectively he outnumbered the understrength division of D. H. Hill he found there he was unable to coordinate anything but piecemeal attacks of one brigade after another, each of which was shot to pieces. Newly arriving Confederates were fed into the lines at the center, while the final of Sumner’s divisions, under MG Israel Richardson, was thrown in for the Union, long after it would have usefully prevented a slaughter of northern men.

Richardson’s numbers did tell, however, as did a flanking attack that managed to penetrate the Sunken Road and turn the trench into a shooting gallery afterwards dubbed Bloody Lane. The Confederates were driven out, then counterattacked, and with no follow-up from any other commands, Richardson was forced to retreat from the ridge line he’d spent so much blood taking. He himself would shortly thereafter be mortally wounded, to be joined by scores of other Union and Confederate officers at all levels of command. The battle was devouring itself, a chaotic frenzy lost to any commander’s control.

There was still one last phase to play out, the diversionary attack in the south that now took on critical importance. Lee was worn out in the north and his center was weak. In addition to the men still positioned on the battlefield McClellan still had an astonishing 25,000 fresh troops in reserve, including new arrivals- more than Lee had had at the start of the battle and certainly more than he had standing after the morning’s fighting. If he had thrown them in in support of the attack from the south Lee certainly would have been destroyed. But McClellan was fully committed to the idea that Lee was baiting him and refused to countenance any plan that left him without reserves to counter what he feared would be a sudden flanking move out of nowhere like the one that had routed Pope. Underscoring this was the presence of MG Fitz John Porter, commanding the V Corps held in reserve, who had played a major (and controversial) role under Pope at Second Bull Run, who advised his old friend McClellan not to take the risk.

So McClellan demurred, hoping instead that IX Corps, under MG Ambrose Burnside would be able to do the work of taking Sharpsburg and cutting off Lee from retreating without McClellan’s needing to take unwelcome risks. The whole course of the battle now turned on the IX. This was not ideal, however, because for all of Burnside’s achievements in inventing guns and facial hairstyles he lacked imagination as a commander and was probably the most luckless leader the Union had. He’d spent the better part of the day trying to force a crossing of a stone bridge across Antietam Creek (now Burnside’s Bridge) before finally being forced to order his men to charge across irrespective of casualties. This was the attack that was supposed to have began at the same time as the initial assault in the north that morning; the supposed diversion was now the main thrust.

They made it across with heavy losses but with the span now secure the whole body now made its way up the hill toward the town, or would have if the bridge crossing hadn’t turned into a massive bottleneck with badly needed ammunition unable to get through. Two hours were eaten up in the confusion while Lee and Longstreet again took the opportunity to reposition their weary men. As it happened, Antietam Creek was easily fordable in a number of places and Burnside hadn’t really needed to bother with the bridge in any case to begin with. But now he was ready, and Sharpsburg loomed ahead. If he took it, Burnside would control Boteler’s Ford, the only way across the Potomac possible for Lee, and thus the Rebel general would be trapped. Burnside would be a hero.

He marched up the hill, taking heavy fire from Confederate infantry and artillery. Some of his more inexperienced units broke under the strain of the days fighting and ran, inspiring others to follow. But Burnside pressed on, confident of success. And he would have achieved his goal, had it not been for the second major stroke of Confederate fortune that day.

A. P. Hill (no relation to D. H.) was an irascible badger of a man who, at Lee’s urging, had just marched his “Light Division” 17 miles from Harper’s Ferry to Sharpsburg, arriving just as Burnside was crossing the bridge. Most of them had just sat down for their first rations of the day when word came that they were needed at the front immediately. In such a foul mood as one might imagine they slammed into Burnside’s corps out of nowhere and sent it reeling. Though Burnside heavily outnumbered Hill the attack unnerved him and he retreated all the way back across the bridge to await further support.

None would be forthcoming. McClellan naturally considered the arrival of Hill definitive evidence that Lee could produce reinforcements at will, and that he’d done enough against the 100,000 Confederates he still assumed were out there. Lee, for his part, fully expected to be attacked at any moment, and spent the rest of the daylight digging in and reforming his tattered lines. But when he finally realized McClellan really did just intend to sit there he declined to press his own luck and took the opportunity afforded him by McClellan’s timidity. Lee simply packed up and left, with the Union Army- despite the mauling it took still more than double his actual size- watching him depart.

The Confederates had suffered something like 30% casualties in the battle as a whole, with some of the units in the thick of the fighting losing more than 60% of their men. Hood, asked by Lee after the fray where his division was, famously responded “dead on the field.” Overall the Army of Northern Virginia had around 1,800 killed and close to 8,000 wounded; these are estimates that take into account the probability that many troops listed as ‘missing’ simply died unaccounted, blown apart by cannons or dying alone and unseen in the forests in the midst of the general chaos. The Army of the Potomac suffered a lower casualty percentage but great numbers of dead and wounded, over 2,000 killed and 10,000 wounded. One unit, the 12th Massachusetts Infantry, lost 67% of its men. The battle did not spare the higher ranks- six generals were killed in the fighting, including two Union corps commanders, and scores more, like Hooker, were wounded.

Hood would describe the fighting in the Cornfield as the worst horror of the entire war- this from a man present (and horribly wounded) at both Gettysburg and Chickamauga. Hooker, with similar experience, shared his assessment. So many bullets had been fired through the dry brown autumn cornstalks that not a single one was left standing after the fight. Hooker said it looked like the bloodstained field had been neatly harvested with a scythe. A writer with the imagination of Hawthorne could make a macabre tale out of that imagery, the story of some dark pagan harvest ritual, human sacrifice and all, complete with the Grim Reaper, all disguised as a thoroughly modern undertaking.

What did this holocaust mean? Nothing very immediately and obviously significant happened as a result of all of that death, so significance had to be found in the aftermath. In the Southern imagination, Lee had fought off an army twice his size and saved his force to fight another day. It would indeed survive to launch another invasion of the North just under a year later, and had that proven successful, one could imagine Antietam being viewed as a kind of Guilford Courthouse, a pyrrhic victory on the part of imperial power that in the end merely showcased its impotence against the forces of independence. But it was not to be. As far as McClellan was concerned he was the hero of the hour, the savior who’d seen off the sack of Washington and sent Lee scurrying back home. The Lincoln administration profoundly disagreed and, infuriated by McClellan’s post-battle dithering, relieved him for the final time. Lincoln then made two fateful choices. The first was to replace McClellan with Burnside, which led to the debacle at Fredericksburg. The second was far wiser. The battle was enough of a victory to provide just enough political cover for the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation.

We all remember our high school history coaches informing us that this document freed the slaves, with perhaps the stray pedantic deboonker in the department informing you that ackshully it didn’t free any slaves. The actual significance of the document requires some explanation. Lincoln had always been anti-slavery without being an outright abolitionist. He believed, correctly, that the Constitution protected slavery as it did all property rights and that absent some amendment neither he nor anyone else could end it. But the war had given him the perfect pretext for a work-around. If slaves were property, and being used for the Confederate war effort / insurrection, then logically that property was subject to seizure under Lincoln’s general authority as commander in chief. Thus, the Emancipation Proclamation, which pronounced all slave held in states in rebellion as being free, could be framed as a wartime measure that would strictly apply only to those states fighting his administration and not to the loyal slave states.

This was brilliant propaganda, with the added effect of making foreign governments henceforth unwilling to consider recognition of the South now that slavery itself was a war issue. While the reality remained that slavery was perfectly legal in the Union throughout the war, in the popular imagination the war could now be conceived of as a crusade against slavery, which is turn is how modern America is programmed to remember it. It remains the one thing that gives the Union government of Civil War era the moral standing it has today, and progressives then and now license to despise the defeated and devastated South to come. From the slaughter at Antietam came the birth of the White Legend of Union liberation to correspond to the Black Legend of Southern evil and depravity.

For my part I see the greatest value in honoring the courage of the men of both sides as they hazarded their lives for their beliefs and their comrades. I think of dim old Mansfield riding off to Valhalla at last; of Hood charging into the cornfield, his men not knowing what stood even at arm’s reach before them; of Richardson, cut down after taking that impossible sunken road. I think too of Samuel Mumma, the prosperous local farmer who’d sponsored the Dunker Church down the road from his barns, who saw his home trampled and burned to ashes in a fight his Mennonite sect had no stake in; what could he do but mutter in his native Pennsylvania Dutch at the savagery men were willing to inflict on one another rather than love each other as brothers.

There are those who think some civil war is coming once more. If you wish to know its character, read closely the story of Antietam. Not for the tactics or the underlying politics or anything like that of course, but to understand the particular mindset that makes things like that possible. A few hundred men planned and organized tens of thousands of other men into a plan of slaughter and destruction against a foe that spoke the same language and worshiped the same God. The people at the top on both sides generally knew each other by name and acquaintance; many had fought on the same side in previous conflicts. Many were related. How little it took in the end for them to be willing to annihilate one another, how few people thought it would come to that? But it did, and if it does again, it could only be worse.

Dunker Church today, from the National Park Service. For more pictures of Antietam, click here.

A great retelling of a horrible episode of American history. I visited Antietam a few years ago while visiting family that lives in that general area. It's humbling to stand on the hill overlooking the field and imagine the scale of what it must have looked like to have so many soldiers marching at once, the magnitude of the violence, and, what always makes my skin crawl, the idea of two lines of infantry just lining up on either side and shooting at each other with no cover and defense to count on except cold and impassive probability that a bullet won't strike you. The natural beauty of the area makes it easy to forget just how steeped in blood it is.

It's also worth noting that the Blair Witch Project was filmed within spitting distance of Antietam and within walking distance of my relative's property and it really makes me wonder why they live there. The scenery is great but... I just wouldn't want to live next to a place where so many people met such a violent end. I have no doubt that kind of bloodshed leaves a tangibly intangible stain on a place.

Amazing story. Thanks for highlighting this fascinating and horrific story of intelligence, courage, cowardice and slaughter. Very very sad.