Autistic Reddit atheists will tell you, whether you invite them to or not, that ackshully Noah wasn’t real and didn’t save all the animals on the ark. After all, they scoff, where are the dinosaurs? A moment’s refection will serve to dispense with this line of reasoning, as dinosaurs are still very much with us, simply in a more human-accommodating, postdiluvian form. Indeed, you may have one in your home right now.

I mean of course birds. Yes, even girlboss scientists have recently conceded what many amateur theorists (and presumably activists among birds themselves) have long maintained, that modern avians are essentially smaller, statue-bedefacating versions of Theropods, that class of dinosaurs which includes the Tyrannosaurus and Velociraptor. That cardinal munching seeds at your grandma’s bird feeder is the descendant of some eight-ton horror from the Cretaceous. They actually wuz kangz and shiet.

Sometimes things are obvious when you look with the right mindset.

As the example of the seagull illustrates, however, there has been a notable decline in phenotypic majesty over the last few hundred-million years or so. What were once hulking, brontosaurus-slaying monsters are now tiny, colorful, harmless creatures, apart from their occasional propensity to drive some of the greatest minds of modernity into madness. If a bird kills a human, for the most part, it’s because it was undercooked. However, there are exceptions.

Among birds, as with people, there are those who keep to the old ways. Birds who make the conscious choice to live according to timeless values, adapting to modernity on their own terms while otherwise holding fast to an ancestral mindset. And while, strictly speaking, they might not approach the size of the greatest dinosaurs, theirs is a tradeoff involving an exchange of pure conspicuousness for an appropriate combination of threat-mass and gray man capacity for moving unnoticed by the dead but watchful eye of Globohomo. There is one bird that exemplifies these principles more than any other: the cassowary.

This guy.

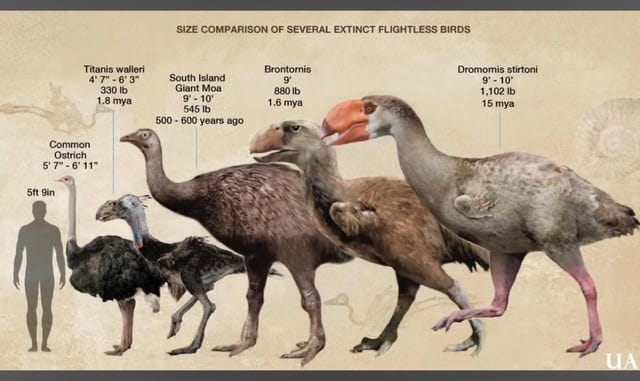

The cassowary is a ratite, a group within the subclass Palaeognathae that includes ostriches, emus, and kiwis. All ratites are flightless birds which lack the characteristic sternum anatomy needed to anchor flight muscles (penguins and other aquatic birds have this setup, but use it for swimming). Interestingly, scientists believe that at one point the birds of this class were equipped for flight, but evolved away from it. While mystifying to gamma nerds, the rationale is obvious from the point of view of Tradition. If stalking prey on the ground was the Way of the Tyrannosaur, so let it be the Way of the Ratite.

It should be noted here that, contrary to what one might expect, the ratites are not closely related to the gigantic and formidable terror-birds (phorusrhacids and bathornidids) of the Cenozoic to the Pleistocene Eras. These horse-eating monstrosities’ sole biological descendent is the seriema of South America, which is not especially remarkable. However, ratites- especially the cassowary- seem to have an instinctive understanding of Evola’s principle that race is as much a matter of spirit as blood, and have chosen a path of differentiated development unrestricted by the limits placed upon them by nature. Informed by their ancestral memories, they seek to impress their will upon their existence and embrace a life of spiritual struggle for meaning.

Reject modernity, embrace terror-birdism.

For example, I mention prey, but it should be emphasized that all ratites are adapted for lives as herbivores. Even the largest living members of the group, the ostriches, only occasionally eat the stray mouse or lizard. The solid bones, menacing strut, and unpredictable aggressiveness are aesthetic choices. But in keeping with their Traditionalist mindset, aesthetics are bound up with moral and political values. The emus, for example, have proven far more successful at defending their territories and way of life from the Australian government than their fellow indigenes, the Aboriginals, defeating said government in war and wringing from them important treaty concessions like being able to drink in Australian pubs.

The cassowary differs from its fellow ratites in that it is wholly aloof in its dealings with humans, not necessarily always apart from them, but always among them, never of them. Native to both Northern Australia and New Guinea, it prefers a jungle habitat where few men dwell in any case. But even among its own kind it demands solitude. Uniquely among ratites it does not form social groups and is not the least bit gregarious, disdaining even the pair bonding of mates that other solitary birds engage in. Interestingly, it is the males that perform brooding and protection of nests, watching over hatchlings until their sigma mindset is fully inculcated and they can be sent out into the forest.

A full-grown cassowary can stand nearly six feet tall and weigh over 160 pounds, the females being generally slightly larger than the males and a bit more colorful. It has dense bones and powerful legs that can carry it crashing through the bush at 30 mph on its three-toed feet, the innermost of which bears a fearsome five-inch claw reminiscent of its Velociraptor forebears. Its wings are tiny and vestigial. Atop the heads of both males and females is a characteristic keratinous crest, again hearkening back to dinosaurs like the Hadrosaurids, the exact function of which is debated. It is quite impossible to mistake the cassowary for anything else unless you happen to encounter one in Jurassic Park.

It will rip you apart.

Almost uniquely among birds, unlike even other ratites, the cassowary has no tongue. It is not silent, however, announcing itself in extremely low-frequency rumbles and sounds described as ‘booms’ by listeners. There is an uncanny valley-quality to their vocalizations, as they do not sound like they ought to be coming from a bird, instead being the sort of thing one might expect from a Ray Harryhausen puppet. Listen for yourself.

Cassowaries have a relatively simple digestive system designed for processing plant matter, and their beaks are adapted for a generalist herbivore diet. Despite this, cassowaries are active predators and have developed complex hunting strategies for a variety of prey. They will, for example, puff out their feathers and lower themselves into jungle pools, allowing small fish to swim in to eat dead skin; they will they quickly contract their feathers and spring out of the water, with the fish trapped underneath, whereupon they drop them on the ground and eat them. They kill smaller birds and bandicoots, pluck crabs from the seashore, and eat a myriad of other things. It should be emphasized that this is a choice, that the cassowary is a hunter because it wants to be, and though it can survive- indeed is adapted to survive- with a vegan lifestyle, it disdains to do so. Cassowaries in captivity will, given the opportunity, adopt an almost exclusively protein diet. The aforementioned gamma scientists have expressed great concern that some eccentric billionaire might create a program to introduce trenbolone and nootropics into cassowary populations, the results of which might be easily imagined.

Cassowaries and humans have complex relations. Unlike emus and ostriches they cannot be truly, fully domesticated, and unlike the chicken-sized kiwi they feel no need to actively hide from us, though most choose to be elusive. Among the natives of New Guinea the Cassowary is occasionally hunted, but even the most attentive student of the jungle has his work cut out for him finding the crafty adults, with a success rate of bagging one in five years considered evidence of proficiency. New Guineans will find eggs and keep juveniles as semi-tame animals killed for ritual purposes, but generally find the adults unmanageable. The Karam people view the cassowary as part of their collective kin-group and treat any violence against them as ritually equivalent to intra-clan killing- it must be done with blunt weapons and the hunter is polluted as if he’s committed manslaughter.

The cassowary is occasionally described as shy and fearful, but this is belied by their indifference to humans when they don’t feel concerned with active threats from our quarter. The people of Australia, unlike the New Guineans, don’t really hunt them, and the cassowaries have responded to the humans deforestation of their habitat by waltzing into mammalian neighborhoods. Sometimes this ends tragically, as when cassowaries are hit by cars, and the Australian government has yet to respond to this crisis with public health warnings as they do with Aboriginals facing similar threats. It is questionable whether this would work in any case though, as the birds are too proud to hurry across roadways and, unlike the Aboriginals, don’t watch much TV.

This is a real ad.

For the most part though, the cassowaries just do what they want. They’re not especially interested in interacting, but they’ll take advantage of free food and the chance to watch normie human society, which they inevitably approach with equal parts grace and hauteur. Knowing their ways can’t but be useful should you encounter one in the wild. Let’s look at some various scenarios.

Here we see one attending a picnic, presumably mortified at the humans’ Poluphemos-like rejection of the principles of xenia. But being a shrewd judge of character, the cassowary no doubt sums them up as hopelessly middle-class and unworthy of his aristocratic character. Notice that he takes and then returns their seed-oil based prolebread in an effort to intimate to them to clean up their diets by its example.

Cassowaries similarly have an inborn noble distain for anything resembling social-media thottery and will become especially offended at humans spoiling their natural habitat with Instagram-rigs.

Sometimes, even when they’re trying to be polite, they simply can’t help but mogg normies unused to their aura.

Don’t bring a rake to a dinosaur fight.

Kylie, evidently the Eowyn of Australia, approaches the cassowary with proper, shield-maiden (sheila-maiden?) deference, offering both food and respect.

One can see recurrent themes in each of these videos. One, the cassowary, beholden to an older set of values than humans can comprehend, rightly conceives of the soft and featherless creatures before it as interlopers in its world, even though in their vain imaginations they’re the ones in charge. Two, it responds best to courteous distancing, even when humans might consider the bird to be the intruder. And three, a creature can be wholly calm and wholly wild all at once, with a latent power most apparent to those attuned to other forces of nature.

So are these stone guests from the prehistoric really as dangerous as their reputations stipulate? Yes and no. As with bears, most injuries result from humans trying to get too friendly. Of around 200 documented attacks, only two encounters were deadly. One involved two teenaged boys in 1926 who thought it would be fun to kill a cassowary that had come into their family farm by beating it with sticks. This proved to be a bad idea, as would have been obvious beforehand to anyone who isn’t a teenaged boy. The other fatal attack occurred more recently in Florida, where a seventy-five year old man was killed in 2019 by a cassowary he owned, but being Florida, someone was going to die like that sooner or later anyway. While cassowaries are often described as the “most dangerous birds in the world,” this is not the same thing as saying they’re the most violent. Natural aristocrats that they are, they cultivate the capacity to inflict harm while manifesting the self-control to unleash death and mayhem only when they deem it appropriate. Would that more humans could do both.

And there is the ultimate lesson. The superficial reading of the cassowary is atavism, a creature representing a kind of throwback to something older and wilder. But such a creature would distain the modern world of humanity like so many other animals that cannot abide our company. But the cassowary, though ancient in its mores, is timeless in its capacity to adapt and thrive, and rightly regards the contemporary as a blighted interruption in a more natural and timeless mode of being. It serves as an example of what the differentiated man might be, having made the conscious choice to become more than what fate assigned him to be, to choose the path of his ancestors and abide in the nature they knew. Let us hope that these creatures long remain with us, and hope as well that they continue to tolerate us as they have.

From the San Diego Zoo. He’s watching you. Become worthy.

The combination of information, adroit references and tongue in cheek interludes make your musings a joy to read.

This was great. Of course it was a Florida Man who was drawn in by their intoxicating primal power and flew too close to the sun...