Some Notes on Reading Old Texts

A Travel Guide

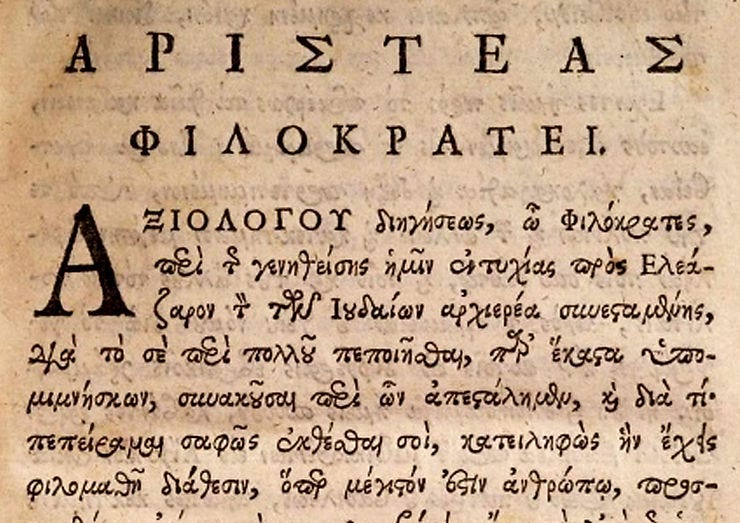

In the course of my recent research on the Septuagint a number of things occurred to me that I thought it might be useful to share. I’ve spent a lot of time over the course of my life looking at old texts and, being used to it as I am, I forget sometimes that most people don’t really have that same experience, even when they are interested in history, religion, philosophy, etc. Things that I’m simply accustomed to as a matter of course must come across to others as odd. I write this in the hope that others might benefit from my own work and, more importantly, the work of others who have dedicated their lives to keeping the works of their forebears before their descendants.

The past is a foreign country. The people who live there speak different languages, have different customs, and above all have different mindsets than we moderns, especially we moderns in the West. I don’t think it is too bold to say that, generally speaking, we find it difficult to make the journey. Divorced from even our comparatively recent history by the imperatives of Globohomo, our ability to appreciate those differences, both subtle and profound, becomes severely limited. And due to our stunted relationship with those who came before us, when we do encounter the past, we all too often fail to comprehend what we see.

One of the wonderful things about Substack is that there are so many people writing (and reading) here who are highly educated, presenting a wide range of knowledge. There are those who know computers, or math, or else have some specialized training or insight into a particular area. For my part, I am trained as a historian. I study the interpreted past- quod ceteris negatum est, cum mortuis loquor- and interpret it in turn. Really, I’m a tour guide, someone who takes people through a strange country and explains the customs of the locals, why they do what they do and how things that happen there affect the nature of life back home.

This necessarily involves texts. History is a text-based discipline. Yes, archeology and experimental science play a role, but ultimately that role is to help generate more texts. Texts are where history begins and where it ends. Being a good historian means being able to read texts, and to really be good, one must be able to read texts in other languages, the languages of primary sources and important secondary research. If one wishes to do original research on the Eastern Front of WWII, for example, one must know, at a minimum, German and Russian, and ideally also Ukrainian, Polish, English, French, Finnish, and several others. And those are normie languages useful for recent history. As one moves further into the past one must master ever-more obscure languages that require much more demanding commitments. Writing about Medieval France means learning several dialects of Old and/or Middle French as well as those of Occitan, now almost dead but once continuous from eastern Spain to northern Italy. If you speak any modern Romance language try to read this:

Lo tems vai e ven e vire

Per jorns, per mes e per ans,

Et eu, las non sai que dire,

C'ades es us mos talans.

Ades es us e nos muda,

C'unan volh en ai volguda,

Don anc non aic jauzimen.Ben es mortz qui d'amor no sen

Al cor calque dousa sabor!

E que val viure ses amor

Mas per enoi far a la gen

Ja Domnedeus nom azir tan

Qu'eu ja pois viva jorn ni mes

Pois que d'enoi serai mespres

Ni d'amor non aurai talan .

Going very far back, to the Classical world, one needs Greek and Latin. My Greek is good enough for translation, as is my Latin, though a bit less so; I began late and sadly will perhaps never reach the potential of what I might have done with them. But I can still read them and I am deeply grateful that I had the chance to spend three years studying Classics and Religion in order to be able to do so. I neglected Hebrew but I’m attempting to ameliorate that. And back further still one needs things like Aramaic, Akkadian (and its daughter languages Babylonian and Assyrian), Egyptian, and Sumerian. These require long and very specialized training at the hands of experts to master. Yes, one could theoretically learn them on one’s own- obviously, the first people to rediscover them did. But those men, scholars like Champollion and Rawlinson, were already masters of numerous ancient and modern languages before they attempted to learn to read Hieroglyphics and Cuneiform, respectively, so in that sense they put in as much work as anyone taking Elamite 101 would today.

And that notion of putting in the work is key. People are interested in the past, despite the aforementioned Globohomo’s best efforts, and there are people willing to take them there. But they are not all competent or reputable. Sadly, there are those who take advantage of the eager but unwary, promising them a journey to Rio but dumping them in a favela. One might think of it as Fyre Festival History, or the Willy’s Chocolate Experience guide to the past. The further back you go, especially to the days of the Bible and anything to do with it, the worse the problems get. Yes, there is a farrago of nonsense out there, but take heart, you can avoid it.

The best way to do this is to understand the nature of texts, what they are, how they are transmitted, and how to interpret them. First, one must understand that a text is not the same thing as a manuscript. The text is the information; the manuscript is its physical iteration (the term technically refers to a hand-produced document, cf. the Latin manus). A text can exist as an idea apart from any particular physical instantiation. Many have, for example, memorized the texts of the Koran, the Book of Psalms, the Iliad, and so on; if all existing manuscripts of those works disappeared, men could reproduce them. In fact, a text necessarily has to exist as an idea before it can be rendered into physical form. One can only write what is first in one’s head. Even if one is making a physical copy of an existing manuscript one must have some idea of what it should look like when it is done, and one’s mental image of the correct text is in turn informed by the perception of the manuscript to be copied. In other words, when I translated the Book of Romans in my 8:00 am Biblical Greek class at the University of Georgia I had some idea going in as to what it was supposed to be, and that idea was in turn informed by other translations I read and the UBS Koine Greek manuscript I was tasked with translating. The manuscript I produced was ultimately the product of my sense of what ought to be, which was in turn conditioned by my experience of the text in various forms.

Because a text is distinct from a manuscript, the former can be much older than the latter. In our time, if one wants to read Beowulf, one turns to a modern English translation of the poem. But more often than not, in more ancient times, men made great efforts to preserve older forms of language and took the trouble to learn them. Sometimes languages (or particular versions of them) acquired such prestige that anything important was necessarily written in them. We are familiar with the Medieval use of Latin in this regard, but the scholars who spoke Akkadian wrote in Sumerian; Byzantines who conversed in Medieval Greek Atticized their written prose, and nothing would do but Persian in the Turkic court of the Mughals. Texts that were passed on would generally experience a kind of formative period where they were seldom static; they either lost material as parts were not transmitted for various reasons or acquired additional material as newer writers added their own contributions to an existing work. At a later point, generally once the text had reached the status of a revered cultural artifact, an attempt would be made to produce an “official” or holotype form of the text, a standard by which manuscripts might be judged.

This means two things. One, the drive to preserve older forms of a language as new material was added to a text means that there are often layers of language in a manuscript, where parts written at different times can be teased out of the text when examined in its original language. And two, one must distinguish between authentic ancient language and attempts to imitate it by those who came after. While this isn’t always possible, with enough work there are often ways to pull apart texts into their constituent layers.

Those familiar with Latin can readily tell Classical from Medieval, and a careful Latinist can even spot differences between dialect zones those respective versions were written when contemporary with one another. To return to the example of Beowulf, someone with knowledge of Old English can spot a chain of transmission of the poem through the main dialects of the language spoken at the time, as one can see the layers within the “Homeric Greek” of the Iliad and Odyssey. To get some idea of what this looks like, here is an example as it might appear in English:

Oure fadir that art in heunes,

Halewid be thi name;

Thi kyngdoom come to;

Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread.

And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.

And do not put us to the test, but save us from the evil one.

Even a casual reader would pick up on the fact that this text is made of of bits from different times, that some parts of this text are older than others, even if the reader doesn’t quite get that the first part is from the 1400s, the second from the 1600s, and the last sentence is modern. But of course, a modern reader isn’t likely to see a text in this form. He’ll be reading the Bible in translation, where such differences will have been smoothed out into a single dialect of contemporary English. But make no mistake, to read older manuscripts of the Bible or many other ancient works is to encounter something that looks much like the example above. A translation gives no real sense of how much a product of different times and places an ancient text can be.

Case in point, to use English once more, “The Reeve’s Tale” from Chaucer’s Canturbury Tales is a funny story of two college students from the north of England who come south to have their grain ground and encounter an unscrupulous Miller, and hijinks ensue. In the modern English rendering, some sample dialogue goes like this.

"Ah, Simon, hail, good day," first spoke Alain."How is it with your fair daughter and your wife?"

"Alain! Welcome," said Simpkin, "by my life, and John also. Now? What do you do here?"

"Simon," said John, "by God, need makes no peer; He must himself serve who's no servant, eh? Or else he's but a fool, as all clerks say.

Our manciple - I hope he'll soon be dead, so aching are the grinders in his head -And therefore am I come here with Alain to grind our corn and carry it home again; I pray you speed us much as you can and may."

You might be thinking, where’s the humor? Here’s the text in Middle English:

Aleyn spak first, al hayl, symond, y-fayth!

Hou fares thy faire doghter and thy wyf?

Aleyn, welcome, quod symkyn, by my lyf!

And john also, how now, what do ye heer?

Symond, quod John, by God, nede has na peer.

Hym boes serve hymself that has na swayn,

Or elles he is a fool, as clerkes sayn.

Oure manciple, I hope he wil be deed,

Swa werkes ay the wanges in his heed;

And forthy is I come, and eek alayn,

To grynde oure corn and carie it ham agayn;

I pray yow spede us heythen that ye may.

It shal be doon, quod symkyn, by my fay!

Still not laughing? “Hym boes,” “swa werkes,” “ham,” and “heythen” are all phonetic renderings of Chaucer’s approximation of a northeast English accent, done for comic effect. “Ham” for example, would have been “hom” in Chaucer’s London-area speech, “werkes” would have been “werketh,” etc. It would be like someone coming to New York from very rural Canada with his sentences loaded down with “aboots” and “ehs." As these stories were meant to be read aloud among Chaucer’s fellow Londoners this would have forced them to try to sound as though they were from another part of the country, one they considered the abode of hayseeds. It is in fact the first example in English of dialect humor. But all that is lost in a modern translation, which makes it seem as though the miller and the students speak the same way.

All this is to say that when one has any novel work done in interpreting a text necessarily involves looking at it in its original language (or languages) or at the very least having a thorough understanding of the mechanisms of how the text was transmitted throughout its existence. One cannot simply pronounce on Homer without taking the trouble to read him in Greek or else to cite others who have read him in Greek and know the textual history of how the Homeric Corpus came to be. Likewise, exercises in comparative literature necessitate not only a familiarity with languages but also a wide background within the two worlds of the literature being compared, both primary and secondary. Textual criticism, hermeneutics, etc. are not exact sciences, which makes it that much harder to know when one has made mistakes, and to let imagination and emotion get ahead of evidence and reason. This is especially true with things as culturally loaded as the Bible.

So I mean to take great care when I write on the Septuagint, as I try to do when writing anything related to history, or anything in general really. The texts deserve this, and you, my readers, deserve it. No book is an accident and neither is its preservation, interpretation, and transmission. All of these things are the proper work of scholars and my hope is what I lack in scholarship I make up for in inspiration. Great work on the subject, and so many others, remains to be done, and I can think of no better audience to appeal to for comment than here on Substack.

Mr. Librarian, good day.

My only comment is a request that you keep sharing your Septuagint journey here.

The only thing I'd add is, hey everybody, please do read older texts whenever you can!

U.S. history as an example, I've my late 1800s The Queen Of The Republics or Standard History of the United States readily available on my shelves and often refer to it when reading today's take on something that happened in the 17 or 18 hundreds. I usually find that compared to today, most often those that were there or who's granddads and uncles were there had an entirely different take than modern authors.