[The date of September 11th is generally the date of somber reflection among commentators, edging too often toward the maudlin, and with no small amount of rationalization. While an attitude of reverence is indeed appropriate, simply recalling the death and destruction of the day I feel induces a kind of fatalism in Americans, the notion that we are to be the passive recipients of the great cultural shifts of the day. For the last twenty years we were told that we needed to fight Islamic militants over there so we wouldn’t have to fight them here; now they’re a voting bloc in swing states. While giving the disaster its due I think it is also appropriate to reflect on triumphs as well as tragedy, and thus I’ve generally sought to offer historical accounts relevant to the day with a different and more positive ending. My previous effort was last year’s “On Another September 11th;” this year I mark the occasion with the retelling of a great campaign that culminated on September 12th.]

Jan III Sobieski was born in what is today Ukraine in 1629, and into a world of conflict. The previous century had seen the Wars of Religion break out all over Europe, with princes backing various Protestant sects contending with rulers who embraced the traditional Catholicism, not to mention the various apocalyptic populist cults that filled the spaces created by the collapse of authority. The settlements arrived at through Peace of Augsburg in 1555 could paper over the problems for a generation or so, but violence was never far from the surface. A dispute over succession in Bohemia led to the The Thirty Years War, which was still raging in the Holy Roman Empire during Sobieski’s youth, as Emperor Ferdinand II fought to suppress Protestantism against the machinations of Sweden and many of his own nobles, and in doing involved most of Europe in a cataclysm that resulted in a third of Germans being killed. Christian nations took the opportunity to settle scores with their rivals; Russia, Sweden, Prussia, France, The Netherlands, Spain, and England each sought to undermine the others, while changing allies in Central Europe as their needs dictated, religion be damned. Catholic France sponsored the campaigns of the Protestant Gustav Adolf- the modern Pyrrhus of Epirus- while Ferdinand relied on the terrifying godless warlord Albrect von Wallenstein.

Sobieski’s own land was part of The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Little remembered today outside of its former territories, it was, in its day, one of the most largest and most powerful countries in Europe, extending from the Baltic to the Black Sea, with some twelve-million subjects of a variety of ethnicities. Technically the personal union of the crowns of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, it encompassed parts of what are today Germany, Ukraine, the Baltic States and various Eastern European countries. The Commonwealth had an innovative elective constitutional monarchy and an assembly of nobles with the right to legislate, a system known as The Golden Liberty. But for all its wealth and power the Commonwealth could not escape the turmoil of the times; it was right in the middle of everything and suffered for it.

Christian feuding created weakness, which invited predation. To the southwest, creeping north through the Balkans like a plague, was the Ottoman Empire. The Sultan of the Turks had adopted the mantle of the Caliphs of old, the Captain of the Faithful charged by Allah to wage war on the Dar-al-Harbi until the infidels finally and totally submitted to Islam. The previous two centuries had seen the destruction of the Roman Empire in the East and the conquest of various Eastern kingdoms like Serbia and Bulgaria; Hungary fell in 1525. Russia, which would later assume the mantle of the fallen Orthodox Empire of Byzantium, was only just emerging from its own Time of Troubles. All of Europe recognized the collective danger in the abstract, but their own petty political squabbles had always taken precedence over collective defense.

Jan’s father was an important nobleman in the Commonwealth, and young Sobieski had a fine education, studying at several universities. His early adult years took him around Western Europe, where he met important figures and learned the major languages. He returned home, and when his country was threatened by a Swedish invasion, he enlisted as a soldier. This was the period in Polish history known as The Deluge, and it was not the only problem the commonwealth faced. Bands of independent-minded freebooters and raiders known as Cossacks had coalesced into various polities under leaders called Hetmen and attacked the frontier as well as the Tatars of Crimea, Muslim groups of Turko-Mongolic extraction. Jan was a natural fighter, and his his abilities were quickly recognized. He rose through the ranks fighting on every front. He became active politically, and represented his country abroad, once even posted in the Ottoman Empire, where he learned not only the Turkish language, but also their tactics and strategy.

One of the greatest and most realistic swordfights in movie history, from the 1974 Polish film Potop (The Deluge). Skallagrim’s commentary is great.

Sobieski commanded one important campaign after another, demonstrating on each occasion his courage, intelligence, and mastery of leadership. He was given ever-greater responsibilities until he finally reached the highest position in the military, Grand Hetman of the Crown. It was at this point, known and respected by all, common and noble, friend and enemy, that with his country under the looming shadow of invasion from the Ottoman Turks, Jan was elected King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania in 1674- Jan III Sobieski. He would have his work cut out for him, as the various modes of religious and political factionalism that had plagued the west had moved east with a vengeance.

Sobieski spent the next nine years building alliances, fending off rivals, forging compromises, reforming the Polish Army, and fighting. He built strong relationships on his flanks, ensuring peace with both the Holy Roman Empire to his west but also the Cossacks to his east, many of whom he enlisted as light cavalry in his own army. But central to his military strategy was the use of elite heavy cavalry, the Hussars, more famously known as the Winged Hussars for their uniquely accessorized armor. They fought with lance, sword, and pistol alongside dragoons (cavalrymen that could also fight on foot), infantry armed with matchlock muskets and battle axes, and sophisticated field artillery. He methodically built up an experienced, well-equipped, and well-organized force, perhaps the best in Europe at the time. It would be needed.

In 1682, word arrived through spies that the Ottomans intended to invade north from Hungary, which they then controlled, and attack Vienna in Austria. This would be a devastating blow for Christian Europe, as whoever controlled Vienna controlled the Danube, and would be poised to move further into Central Europe, threatening Italy, France, and Germany. The The Ottoman Empire was certainly the most powerful Empire in Europe, able to field massive armies on three continents, and the Christians of Europe had invited this assault with their constant internecine war. The question of the hour hung before the kings of Christendom like an image of the doom of the world. What was to be done?

Pope Innocent XI understood that the Turks’ threat to turn St. Peter’s Basilica into a mosque was not idle boast. Unlike his current successor, whose main preoccupation is assisting the Muslim invasion of Europe, Innocent XI was no Marxist but a man who understood a profound threat to his civilization when he saw one. He successfully brought together numerous Catholic countries- his own Papal States, the Serene Republic of Venice, The Holy Roman Empire under Leopold I, the Duchy of Lorraine, ruled by Leopold’s brother in law Charles, and other smaller powers, including those parts of Hungary that were still free, wild Zaporozhian Cossacks from Ukraine, and even some Muslim Tatars eager for loot and glory. This was the Holy League, an older idea from a more chivalrous age, resurrected for war once more. And to command them all, along with his own army, could be none other then Jan Sobieski.

Jan had not only the honor of his nation but the salvation of an entire civilization on his shoulders. He had in total something like 90,000 men, a huge army at the time, but dwarfed by the 170,000 mustered by the Turks. By bringing battle to them, Jan risked the destruction of his force which would leave little in the way if the Turks were victorious. And as the Turks marched against Vienna and laid siege to it, Europe held its breath as the armies sent to stop them marched off to converge there on their foes, either lifting the threat posed by the Turks or being annihilated thereby. Would Sobieski arrive in time?

The brave Viennese held out for two months against the bombardment of the Turkish siege guns and repeated assaults by wave after wave of shock troops, including the best of the Ottoman elite, the Janissaries. These were a corps of fanatical slave soldiers raised up from kidnapped sons from Christian families, the product of the cruel devshirme tax levied by the Turks on their dhimmi subjects. Sappers dug under the walls, intending to fill the spaces beneath with gunpowder and blast their way into the city. Not but 16,000 stood against ten times their number, and the only thing uncertain was whether the alliance would arrive before the walls were turned to dust.

Strangely, however, the attack was not as deliberate as it might have been. Kara Mustafa Pasha, the Turkish commander-in-chief, was eager to capture the city with diplomacy rather than violence, repeatedly urging the Viennese to surrender peacefully between attacks. Kara Mustafa would control the city in that event, whereas if the army took it by force, it would be open to the plunder, rape, and enslavement mandated in Islamic law. His greed made him hesitant. The Viennese, in any case, had no reason to trust in his promises and duly kept up the fight.

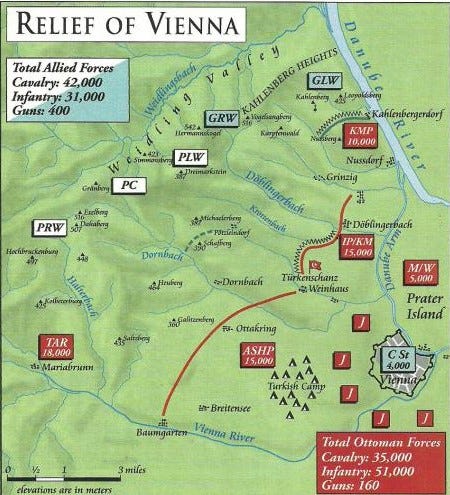

At last, on September 11th, 1683, The first of the allies began to arrive. Leopold and Jan combined their main forces and prepared to attack. And so it was, early on the morning of September 12th, that the infantry of the Holy Roman Empire launched itself against the Turks’ left flank. The fighting there would last all day. Meanwhile, Jan marched against the Turkish right. Now engaged in the front and on both sides, the Turks, though still greatly outnumbering their foes, were unable to cope with the mounting chaos. Their allies in their rear began to lose interest in participating.

And then, at around 6:00, came the final blow, a sight never seen before or since. Emerging from the forest on the Turkish right came 18,000 horsemen, most of whom were the famed Winged Hussars. At their head was Jan himself, 54 years old, sword, lance, and pistol at hand. They cantered down the slope of a hill, and then came the order to charge, the largest cavalry charge in history, 18,000 screaming men, horns, and horses, colliding with the Turkish forces in a tsunami of stabbing, hacking, and shooting. Men and animals were struck down and fell to the earth beneath the pounding hooves of an enormous mass of violence that pushed ever forward, driving the Turks back into their own camp and away from the field as fast as they could manage. It was a complete rout, the Turks were crushed, and Vienna was saved.

It’s not exactly Peter Jackson, but for the budget they had the producers of the joint English, Polish and Italian film “The Day of the Siege” did an admirable job.

After the battle, the Pope formalized the Holy League, an alliance of Christian powers dedicated to eradicating the threat of Islamic conquest, similar to the current Pope’s brave efforts against climate change. Jan III Sobieski went on to further victories in what became known as The Great Turkish War, joined also now by Russia. Under the leadership of a king raised up to power and majesty by God, man, and nature itself, warring kings were able to put aside their squabbles and feuds and take advantage of a God-given opportunity to win the truest glory of a leader, defending faith and nation from those who would defile them. Kara Mustafa Pasha was not quite so fortunate; as was the custom of the Ottomans, he was strangled with a bowstring for his failure.

Jan III Sobieski died twelve years later at the age of 66, and is remembered by his people as one of their greatest heroes. When you see twaddle in the news about Poland and Hungary or anyone else in Eastern Europe turning to “authoritarianism,” understand that by this word the reporter means they are a people who have not forgotten their past. And those same people know that when the reporter says “liberal democracy,” he means the Kara Mustafa Pashas of the modern world. Rest well, King, and may your spirit return to arms at the hour of your people’s greatest need.

To conclude I offer the words Jan Sobieski spoke as he entered the city of Vienna, battered but victorious: “Veni, Vidi, Deus Vicit.”

I came, I saw, God conquered.

…

tl;dr just watch the Sabaton video:

When discussion is had of the GOATs of European royalty, you can't have the discussion without Sobieski. His victory at Vienna is nothing short of the stuff of legends. I like to think I'm well-versed in history, too, but I've never heard of the "The Deluge" before - though, now I'm probably going to have to binge read about it. It sounds remarkably similar to the Time of Troubles in Russia, when the entire country was basically being torn apart in all directions.

That all being said, I was recently in Vienna and, for as momentous as the breaking of the siege was, there was remarkably little to commemorate it in the city. There are statues of pretty much everyone of any repute that played any part in the city's history, but none of Sobieski. There's not even a monument commemorating the event that I found. I did discover, while doing research for this comment to make sure I wasn't just talking out of my ass, that there was a statue made of Sobieski that was intended to be placed in Vienna in 2018 to commemorate the 335th anniversary of his victory, it was rejected by the city's mayor for being "anti-Turkish". Apparently, even in Poland, where the statue was ultimately erected in Krakow, it was controversial because, er... something something Anders Brevik because he mentioned the Siege of Vienna in his manifesto once. And he's not even Polish.

Laughable.

We should remember both Sobieski’s victory and the great Croatian victory of 1566 at Sziget. The gallant defenders died but so delayed the Turks that they were unable to mount a similar offensive until the siege of Vienna a century later.