Years ago, at another teaching job, I ran a club called the Museum Society. The term was meant in the broadest sense; we explored everything the muses had to offer, looking at philosophical themes in art, music, and (most accessibly to the kids) movies. Every week we would watch something and analyze it according to some conceptual category, and for the notion of ‘bad’ we viewed Birdemic: Shock and Terror (2010)

I’ve written about this film before, but if you haven’t seen it, I coined the term Artism to describe director James Nguyen’s bold fusion of cinema and autism spectrum disorder in creating a incomprehensibly powerful vision of environmental something. Much like Neil Breen, Nguyen is one of those filmmakers known for creating ‘so bad it’s good’ content, earnest but inept media that has enough heart and oddball appeal to attract a cult audience. It’s hard to find numbers, but it seems likely that these sorts of movies generally turn a profit, as fans (Birdemic has 75% 5-star ratings on Amazon) can’t wait to cringewatch and the budgets are quite low. What you save on CGI Josh Brolin will more than pay for all the denim, tuna, and satellite dishes needed.

If you’re thinking these scenes make more sense within the context of the movie, that’s because you haven’t seen the movie.

The common trait of movies like this is that their badness is foregrounded- unintentionally and generally obliviously- by their creators. The entertainment value lies in the space between what those creators envisioned and what ended up on screen. There’s an entire collection of missing elements- coherent narrative structure, believable visual effects, competent acting, etc.- that makes for something so entirely unlike what was obviously intended that the impact is humorous, like a child mispronouncing a word so badly that it ends up sounding like a different and much funnier one: Poopsicle- The Movie! And for all the mockery such films receive as aesthetic works, there really is something pure and childlike about them (not withstanding Breen’s penchant for nude scenes featuring himself). Even if pretense is intended, the filmmakers utter ineptitude means that they end up producing work that, if nothing else, is intensely emotionally revealing and honest. Mark Region bared his soul to us in After Last Season (2009), and written on his open heart are three letters- W . . . T . . . F.

Try to figure out what this is, I dare you.

The proof of the authenticity of this sort of filmmaking is that it can’t be faked. Absent CTE, a normal human mind simply can’t attempt something like this and make it work. If you try to produce your own good-bad movie you’ll inevitably fail because you’ll be trying to make something that makes no sense, whereas a true GB classic is perfectly reasonable in some lunatic’s headcanon and only comes across as odd to those of us who don’t have to lie on forms to buy firearms. The best one could do is something like the Sharknado series- films that are intentionally cheesy and tongue-in-cheek but are made by competent directors and actors.

“If I wear a suit to the gun store, I can tell them I need a pistol for my Congressings . . . pure Breenius!”

But what if instead a director attempted a different challenge? Suppose that instead of making a film so inept that the worst parts were so overwhelming bad that anything competent actually seemed noticeably out-of-place, a filmmaker tried to hide as many stupid things as possible behind distracting, well-executed superficiality. Rather than a magic trick where everyone but the grinning idiot magician can smell the dead rabbit before it’s pulled out of the hat, imagine a show where you’re so dazzled you don’t even notice the blond assistant in tights is picking your pocket. And what’s more, when you really think about it, it was pretty low effort; the real challenge for the performer is putting in the least actual work possible. That is the magic of what I call Cinéma Médiocrité.

The key feature of CM is a core that is equal parts empty and nonsensical hidden beneath enough gliding that you never suspect the whole thing isn’t gold. There are plot holes, continuity issues, leaps of logic, etc., but you don’t notice them because you’re swept up in the overall experience. It’s made by a director who can make a good movie, but in some instance makes a (probably though not necessarily provably) conscious choice to bait the public with pure crap and see what he can reel in. Done well, there will be money and accolades that will still be there long after more astute critics suspect something is up.

A great example of what I mean is the 1997 film The Lost World: Jurassic Park, commonly called Jurassic Park 2. The original movie made over a billion dollars on a $63 million budget, so a sequel was pretty much inevitable. However, reviews of the latter were mixed, and director Steven Spielberg himself expressed disappointment with the final product. But despite its problems, people still paid to see it in droves and The Lost World didn’t disappoint at the box office, making $613 million on while costing nearly the same to make as the original.

At the level on which the film works, the audience is met with all the superficial markers of a well-made movie. The camerawork and other technical aspects of filming are all top-notch. John Williams delivers the best score money can buy. The actors are talented. And of course, the special effects are groundbreaking. If you’re in a theater in the summer of ‘97, eating popcorn alongside 200 other eager viewers, shuddering all at once at the same jump scares and chuckling at the odd laugh-line, its probably enough to carry you through. You’re not especially even likely to reflect much on what you watched, as the overall positive impression the film made is pleasant to recall, whereas if you really stop and think about it, things might occur to you that cause you to feel differently.

The movie is nearly wholly nonsensical. The protagonists as individuals are depicted as completely misaligned with what their characters are supposed to be. In he first movie, Jurassic Park founder John Hammond believed that people would literally spend any amount of money to see living dinosaurs. In the sequel, he’s convinced that if people see pictures of them that they’ll insist on their being left alone to live as nature intended, despite their being the wholly artificial products of genetic engineering by a for-profit corporation. Ian Malcolm in the first movie was a chaos mathematician with a carefree, rebellious nature. In this, he’s just a dutiful boyfriend and father. His girlfriend, Sarah Harding, is supposed to be an expert in the behavior of dangerous animals and has been on the (newly introduced) second dinosaur island for some time, but repeatedly interacts with young dinosaurs in a way that endangers herself and her friends for no good reason. In fact, the good guys cause every problem in the first two-thirds of the movie and have to be rescued by the supposedly evil antagonists, who manage to get them off the island at the cost of many of their own lives. Vince Vaughn’s Nick van Owen inexplicably disappears at that point, despite being a main character. Malcolm and Harding are conveniently nearby for the beginning of the final act, which is one of the most bizarre and incoherent scenes I’ve ever witnessed in a major movie.

To set the stage, the evil corporate people have captured a Tyrannosaurus and are shipping it to San Diego on a cargo ship. The scene opens with the harbormaster trying to get in contact with the ship, but having no luck. The ship crashes into the dock, whereupon the workers present discover that everyone onboard is dead; the viewer sees a severed hand hanging from the steering wheel. Then, someone- for reasons- randomly opens the hatch, and out springs the T-Rex, ready to go on a rampage through the city!

For this to make sense, the dinosaur- which was previously established to have been both sedated and locked in a special purpose dinosaur cage- must have woken up, picked the lock, then climbed the human-sized stairs out of the hatch, which it hotwired to open. Then this 40’ long, 10-ton animal must have silently stalked around the ship, picking off the crew one-by-one, including stealthfully entering the cabin and neatly severing the hand of the helmsman at the wrist without damaging anything, before locking itself back into the hatch, all before anyone could call for help, and without there being any cameras or alarms to alert anyone.

There is an entire subcategory of videos on YouTube dedicated to trying to make this scene make sense, which is a testament to the power of this work of Cinéma Médiocrité. People want it to be good, so they’ll put in the work to make it so, positing that some velociraptors must have snuck on board or something similar. Had Spielberg bothered to think of that, it might have worked, but that was not the case (it also would have been a great place for van Owen to have ended up, as his character was a radical environmentalist and it would have been plausible that he lost it on the island and was releasing the Tyrannosaurus as revenge). Great CM is a successful bluff; people are so mesmerized by what they think they’re watching that they’ll fill in the gaps in their heads, regardless of what’s onscreen. It’s a type of rationalization, resolving the cognitive dissonance created by the distance between their unconscious expectations and their conscious experience.

This need to force the mind to accept crap as gold is essential to successful Cinéma Médiocrité. I can recall seeing numerous videos about supposed ‘leaked scripts’ during the filming of Prometheus (2012). Everyone was eager to see what Ridley Scott was going to do with his long-awaited follow-up to the Alien franchise. All of the leaks were fake, but pretty much every one of the videos I saw featured movie ideas that were- without exaggeration- actually better than what ended up on screen. Much like with The Lost World, the excellent visuals and surface-level aspects serve as gloss for a core of absolute nonsense. None of the characters behave like they’re supposed to; one scientist decides to pet a hideous penis-cobra monster like it’s a stray puppy and dies stupidly. When they finally awaken the alien bodybuilder who presumably created the maps that led the crew to his planet, he just starts killing them for no reason. More stuff like that happens, then the movie ends on sequel-bait, as scientist Shaw and android-head David fly off to find the aliens’ home planet to ask them why they want to kill all the humans. The sequel, Alien: Covenant (2017), just sort of forgets about all that, killing off Shaw before the movie, and has David invent the Xenomorph aliens, which makes no sense given the timeline Scott had previously established. Again, there are scores of fan videos dedicated to putting in the work Scott didn’t bother with, all of which involve Q-level 5D chess explanations proving that, if you look at it a certain way, Scott’s still got it.

I mean, it looked so cute . . .

Martin Campbell did in in Casino Royale (2006). Why is the bad guy an evil banker when he could make the kind of money he’s dealing with as a normal one? Why was Plan-A a complex international scheme to blow up an airliner and profit from put options, while Plan-B was to spend two days gambling and easily and legally earn $140 million? Why was he any kind of banker; why not just do that all the time? Christopher Nolan- whom I think is the greatest living director- did it too. The Dark Knight Rises (2012) features a similarly convoluted plotline whereby supervillain Bane violently invades the Gotham stock exchange in the middle of the day in full view of the media and executes a cyberattack that bankrupts billionaire Bruce Wayne. Despite this, no one apparently considers it plausible that fraud might be at work, and Wayne is just completely broke the next day. We see the him getting his car repossessed (was he making payments?) and the lights getting turned off at Wayne Manor (was he paying the power bill day-to-day?) before Bane beats him up in a fight scene choreographed by Western Union and throws him into a hole in a desert somewhere. He manages to climb out and then is just back in Gotham, because f*** you.

“Almost” is doing a lot of work there.

What unites these films is that they were helmed by talented people who knew their projects were pretty much guaranteed paydays and, to one degree or another, they phoned it in. But don’t confuse indifference with laziness. It’s very easy to screw up Cinéma Médiocrité. If you doubt me, consider the Simple Jack of the genre, Jaws: The Revenge (1987).

“This time, it’s personal,” was the actual tagline.

As the title indicates, the plot of this movie is that a shark wants revenge. This isn’t a magic shark or a cyborg shark; it’s a biologically normal great white shark looking for payback. Also, this isn’t the shark from any of the previous three films, all of whom were killed in their respective climaxes. This shark wants vengeance on behalf of sharks in general. Despite the fact that presumably lots of sharks are killed by humans every year, it singles out the Brody family from the series as its focus, knows where they live and when they’re in the water, and seeks them out. If you’re thinking that sharks can smell blood something-something, it also goes after the widow of the main character from the first movie, apparently having found their marriage license somewhere.

The easy part about using sharks as antagonists is that their motives are easy to understand- they’re hungry. This film forgoes anything so obvious. The hard part about using sharks as antagonists is that they’re generally pretty easy to avoid. If you stick to building sandcastles, you’re good. Thus, there’s usually a need for some contrivance to get the main characters within bite range. Jaws: The Revenge just ignores this point and has the characters continue to hang out in coastal areas despite the widow’s (correct) belief that a shark is her opp. Her plan to avoid her cartilaginous foe is to leave New England and go where she knows she’ll be safe- the Bahamas. The shark, presumably with the computer assistance of the League of Shadows, hacks her travel agent and follows her there, where she’s fortunate to be saved by Michael Caine, who is totally in this movie.

Poor Joseph Sargent (he made The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, after all) tried his best, but this was the fourth film in the series and the audience’s willingness to suspend disbelief had worn thin. Perhaps if he’d had CGI or Hans Zimmer he might have pulled it off, but what he ended up making was the equivalent of brutalist architecture without the pretentious insistence upon its own brilliance. If making Cinéma Médiocrité amounts to a bluff, Sargent had a tell that amounted to a Tourette’s tic, and well . . .

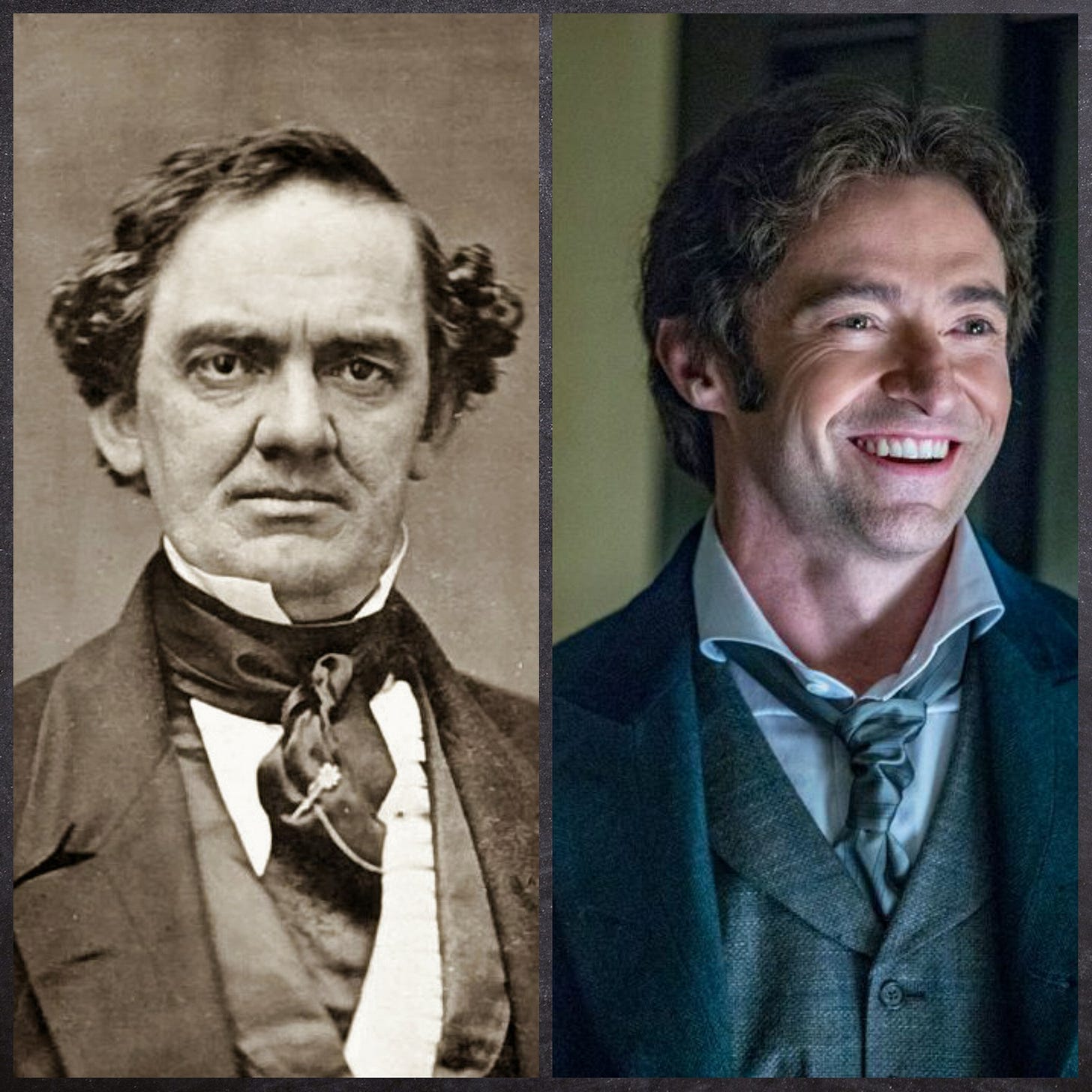

Perhaps you’re thinking, “Librarian, it’s not that serious. It’s a dinosaur/ alien/ spy/ superhero/ monster/ whatever movie.” If so, well, take a moment and do some meta-thinking about your expectations. If I were to tell you a story- any story- in person, and that story had gaping narrative holes, leaps in logic, spurious contrivances, and inconsistent characterization, you would find it painful to listen to me, and you would perhaps even be insulted that I was trying to pass something so incoherent off on you. We think in stories, and instinctively find nonsense uncomfortable- humorous at best and painful at worst. A good lie, after all, must slide painlessly into our expectations, and can only do so by resonating with what we think we know about the world. And if we allow a certain kind of crapulence to slide right by, its because it succeeds as a form of deception masquerading as creativity- art in its own right, perhaps, but still as subtly mendacious as one of P. T. Barnum’s humbugs.

The most meta thing about the 2017 biopic was that it successfully made audiences believe that Barnum looked like Hugh Jackman.

This is important because it’s not merely movies that do this. Just as Industrial Light and Magic and a big-name director can help complete crap slide past the critical faculties of people who just want to be entertained, so too can a masthead like the Atlantic and a lot of jargon disguise a program of ruinous and pointless chaos that will destroy human lives in exact proportion to the amount of problems it doesn’t solve. Yes, the plot of this feature is that elected officials firing bureaucrats amounts to regime change. Once you factor out the prestige and the PhDs involved, and look at it devoid of presumptions and expectations, it’s really just kind of stupid. Say what you will about Neil Breen, no one actually dies based on what he says. And the world should be thankful for that . . .

How did I not know of the genius of Neil Breen until this day.

Currently, DC is in the midst of a bloodless purge.

It is like nothing else within my lifetime, and FDR's '33 ascension to power is the closest I've found in the US context.

Interesting times...