A friendly response to

.This is a quick, inspired intermission; my series On Teaching will continue in my next post. This essay contains spoilers, but you should have read the novel anyway.

I was in my mid-20s before I knew there was such a thing as Classics. I knew that people still studied Ancient Greek and Latin somewhere but I suppose I never put it together that there were high schools and colleges out there for people not like me where those languages where the center of entire programs of study. I was thus 29 when I took an break from an unhappy experience in an MA program in history to pursue what I thought would be a couple of classes in introductory Ancient Greek at the flagship state university. This turned into three years of a Classics/Religion dual major. I was unable to finish those programs due to running out of money, but I count those years as the happiest of my academic life, and it is my deepest regret that I was unable to continue formally along that path.

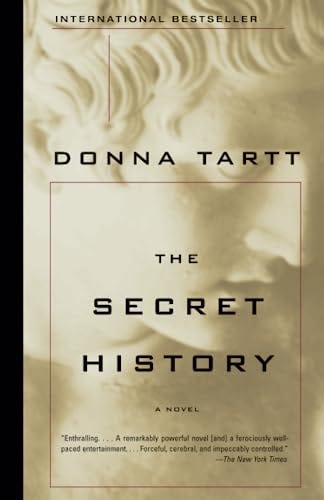

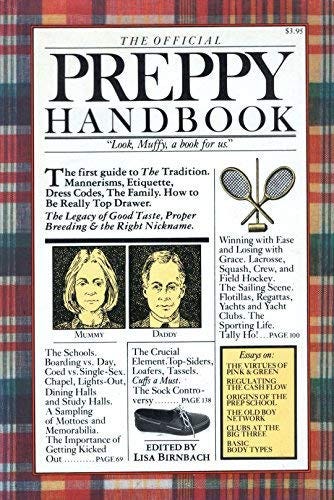

So far as I am aware, everyone who studies Classics, formally or as an autodidact, has read Donna Tartt’s classic (allusion intended) cult (ibid) novel The Secret History and has formed strong opinions about it. It is loved for many reasons. The first thing one must know about Classics students is that they are profoundly weird people. I remember once in Greek 1002 when the professor announced one Friday that she would be getting a teaching award at the homecoming game that weekend. The school is a major force in the SEC and the football program nationally famous. The stadium was a short walk from our building. She came back in Monday and announced to the class how surprised she was that there were so many people in attendance at the game, and to a man and woman my classmates were incredulous that such a crowd had assembled. They had no idea that football was a thing. The strangeness of the sort of person who pursues ancient languages is well-captured in the main characters, especially the enigmatic Henry Winter. The novel also has more Easter eggs than the White House lawn in April, and not merely classical references (Edmund’s nickname, Bunny, is straight out of The Official Preppy Handbook). It’s the kind of fiction that makes well-read people feel like they’ve been invited to a party where everything is familiar and from which the normies have been excluded, which is every nerd’s secret fantasy. And most of all it is simply a great story, not a happy one, but a well-crafted narrative of obsession and descent into tragic evil, though nothing is framed in explicitly moral terms.

Another classic

I would agree to all of those things and offer yet another reason for its appeal. I believe that The Secret History is also a great and distinctively American novel. I think that one of the major and overlooked themes of the book is the character’s longing for rootedness and acculturation, their sense of alienation in their American surroundings, their culture cringe, and their ultimately tragic attempt to transcend their particular circumstances for something they see as more authentic. I think there are also lessons for the reactionary in this; though I would not call it a purely reactionary text, I believe it can be read that way. There are limits to what one can will oneself to be, and being a part of a colonial culture means necessarily growing apart from that of the mother society. To fail to do so, to attempt to hold in place in a fixed way the culture of the ancestral homeland in a different place under different conditions is to bind a sapling into a bonsai tree forever, an immature imitation of what nature would have, greatness circumscribed by fear, tragedy brought on by hubris.

To begin with, there is the narrator and main character of the novel, Richard Papen. Richard is from Plano, California, a fictional place that evokes the well-known Plano, Texas. Texas and California in turn evoke distinctly American archetypes, the former being the setting of cowboys, Indians, and frontier life, the latter being the end stage of that frontier, a progressive utopia of material abundance and middle-class security, a showcase to the world, via Hollywood, of American cultural power. Richard has neither prosperity nor security; he grows up in a miserable exurb in a dull, petit-bourgeois family which dislikes him mostly for his general unhappiness at his circumstances. Richard longs for more, not for more money or status, but for beauty. As he tells the reader, his fatal flaw is “a morbid longing for the picturesque at all costs.” He discovers, to his cost, that he is a Californian “by nature.” Putting this together, one has a man who wants more that his Plano surroundings can offer, who at first believes that what he seeks is transcendence. But that word, “picturesque,” sums it up; he wants the kind of experiences and surroundings that can be contained in post-cards. Indeed, he comes to the main setting of the novel, the fictional Hampden College, because of the attractive brochure. He thinks he is different than his fellow Californians in his pursuit of academic life, but ultimately, he, like they, is shallow and superficial. His Californianess, his Americaness, is uninterrogated. He thinks he can run from it, but like the fate of Oedipus, it finds him. He begins and ends his story there. Americans are a nation of runners; we escaped Europe, we fled the coast for the prairies and the cities for the suburbs; we flee blue states for red and public spaces for private entertainments. We only emerge into distinctiveness when we stand fast in our places, hold, fight, and create.

The great American pastime

Hampden College is in New England, a place representing a people’s attempt to remake the Old World society they had come from, characterized by a pervasive fear of losing one’s Englishness to the wilderness. The frontier was not promise to the Puritans, but the abode of Satan, who dwelled there with his Indians, waiting to lure the unwary into a savage life. Still, inward they penetrated, destroying and building and moving on, a great churn of people and culture, looking westward for life and back across the ocean for how to live it. Hampden is more specifically located in Vermont, that strange and haunted land, the American Arcadia, the abode of some of Lovecraft’s strangest horrors as well as the real-life Bennington Triangle (Tartt based Hampden on her experiences at Bennington College and there are elements of Bunny’s death that are allusions to the mysterious and unsolved disappearance of Paula Jean Welden. Interestingly, there is an oblique reference to the events of The Secret History in Bret Easton Ellis’ The Rules of Attraction on the part of Sean Bateman, brother of the more famous, and dark American archetype, Patrick Bateman- more Easter eggs).

He’s not wrong.

Unsure of what he wants to study at first, he comes to the acquaintance of an odd and insular group of Classics students. The leader of the group, through force of personality rather than charisma, is Henry Winter, a linguistic prodigy and Sam Hyde-esque physical nasty beast. Henry is a mix of new money and old tastes; he wears ridiculously out-of-date English suits around an American campus in the late 1980s, the sort who can read hieroglyphics and has never seen a television show. He is the most complex character in the novel, his personality revealed through his interactions with the others in the group. Capable of great warmth (he saves Richard’s life at one point) and self-sacrifice (at the end, he kills himself to spare another friend a probable prison sentence) he is also possessed of a great darkness and capacity for violence. He is also the least rooted of the characters. While the rest have some connection to some actual place, Henry is briefly noted to have come from Missouri, and little more is said or made of that. Missouri, notably, is at the geographic center of America, and in a sense, Tartt is telling us that Henry, the character who longs the most for culture, while also being the most deracinated, is also, at the same time, the most American of the lot.

This is how you will now picture Henry forever.

The other characters in the group include the twins Charles and Camilla MaCauley, Francis Abernathy, and Edmund “Bunny” Corcoran. Each of them in their own right represents a kind of stunted refusal to mature, a clinging to cultural artifacts rather than growth and creativity. The twins and Francis are East Coast old money, with the same sartorial affectations as Henry. Charles and Camilla are between themselves incestuous; Charles has hook-ups with Francis, who is homosexual, and Camilla lives with Henry for a time in a physical relationship. Richard carries an unrequited love for Camilla. Their relationships with each other mirror their relationships with culture, sterile and derivative- they long for substance but accept semblance. Like the pyramids and Roman ruins of Las Vegas, like the prose of James Fenimore Cooper or Washington Irving, they look to models to copy rather than resources to build upon.

Bunny is the most interesting of the group. He is the most characteristically culturally American of them and for that reason ultimately and necessarily the object of the group’s murderous impulses. Bunny’s father was a college football player, at Clemson no less. He has a large and close family. Alone among the group he has outside friends and a girlfriend whom it is clear he intends to marry; at one point the group envisions him manning a grill surrounded by children. Bunny is good-natured (at first) a reader of comic books and generally attached to popular culture in a way the others abhor. He is, Richard admits, the sort of son every father secretly wishes he had. But he too has a dark side. Bunny is ignorant, a bigot, and though he wishes to give the impression he comes from money he is actually chronically short of cash and frequently duns his friends, especially Henry, for financial support. His prosperity is an illusion fueled by debt, which is the most American thing about him.

Richard admits it is a mystery why the group accepts him and why he, for his part, wishes to be a part of it. Bunny only knows Greek by the fluke of it being a part of his special education program for dyslexia; he has no interest or aptitude for academics and Richard doubts he will even graduate. Of all things, he is particularly close to Henry, the person he least resembles, at least superficially. A clue lies in Richard’s discovery that Henry also might not graduate Hampden, not because he is a poor student like Bunny, but because he is too smart to care. Their lives intersect in that neither really belongs in college, and in fact, college is in a sense holding each of them back from the future they would otherwise have. College in the end destroys them both.

This destruction comes through the mediation of their teacher, Julian Morrow. Morrow is an old money socialite who associated with T.S. Eliot before becoming an academic. The mention of Eliot is significant, a native of Missouri from a Boston Brahmin family, a man who renounced his American citizenship to move to England. Much like Ezra Pound, he culture-cringed, though the latter did so to the degree that he actually broke. Morrow too plays the role of Old World intellectual, seeming to pass on ancient wisdom, but actually planting the seeds of longing for something beyond their ability to grasp, a direct experience of pagan spirituality. For Morrow this is a kind of play, as he actually terms it, and though he seems to care, in the end, he is a kind of vampire feeding on the youth and energy of his charges, like a decadent British Earl marrying a New World canned-goods heiress. The group’s mistake is to take him at his word, to seek to actually enact a Bacchanal, and it is they, not he, that pays the consequences.

It is at this point in the novel, when the group begins the series of experiments that will lead to the first of several deaths, that Bunny’s role becomes key. Bunny is simply too American to go past the limits they must transcend. He simply will not take the ritual seriously, refuses to fast, and generally just causes problems. It is only when they leave him behind that they are able to finally move beyond LARPing to an actual encounter with the pagan divine, in other words, when they most fully shed their Americaness. But, as Aristotle would have known, outside of community there are only gods and monsters; they encounter the former and become the latter, as in their inhuman frenzy they murder a local farmer.

That’s the government’s job.

Bunny and Richard both discover this independently. Neither one has any moral qualms about the murder, and neither feels any sense of loss or connection to the nameless victim. But while Richard simply accepts that his friends are murderers and prefers to continue things as they have been, Bunny is incensed that he was left out. The shift is interesting; Richard remarks that the revelation of the murder simply brought out of Bunny his usual characteristics in an exaggerated way. He was not different but more than he had been. His crudity, his bigotry, sexism, etc., all manifestations of his exaggerated, stereotyped American character become the real voice of nemesis to his friends, reminding them that despite their experience they were still who they were and where they were. They had transcended nothing and Bunny was the living reminder of that. Bunny has to die.

In true Greek fashion, their attempt to undo their fate led them further along the path to it. After they murder Bunny events are set into motion that destroy the group and their comfortable world. They turn on one another, are consumed by vice, and each comes to a tragic end, tragic in the fullest dramatic sense, great souls destroyed by fatal flaws. Julian abandons the group when he learns of Bunny’s murder, not because of moral qualms but because the crime disturbed the illusion of refined and well-bred youth he fed upon. Henry shoots himself to cover for Charles, who has shot Richard in the abdomen; Henry’s wound is to his brain, Richard’s to his stomach, some symbolism there. Charles ends up washing dishes in a diner in Texas, a lonely American in a lonely frontier, while Camilla ends up alone tending her elderly grandmother, the lonesome steward of something ancient and moribund, unable herself to create relationships or new life. Francis ends up in New York, married lovelessly against his will to a vacuous blond woman who plies him with mass-market magazines. Richard writes his secret history from the California he tried so hard to escape, a professor of English rather than the Classics, a subject he had earlier noted was a comforting respite from the hard work of Ancient Greek. They have all met their fates; they are all different sorts of lost Americans, forever past reaching the promise of their youth, condemned to mediocrity and loneliness in a world that will understand them less and less with the passing years. They belong to the past, but the past is not theirs, for they will not build upon it, but only watch it fade away.

The epilogue features an interesting exchange. Richard recalls a dream where he finds Henry in a strange modernist museum, where images of past marvels flicker in a kind of display at the center. Henry stands there watching it. Richard informs him that everyone thinks Henry is dead, to which Henry responds, “I’m not dead . . . I’m only having a bit of trouble with my passport.” It is notable that at this juncture that the notion of identity comes to the foreground. “My movements are restricted . . . I no longer have the ability to travel as freely as I would like.” His afterlife is experienced as confinement, the awareness that he is not free to remake himself and his identity. He cannot say where he is: “that information is classified.” When asked, if the place he is in is open to the public, he answers, “not generally, no.” Everything comes down to this: he cannot be other that what he is, where he is, but he does not know either of those things. He is alien to what is around him and can only glimpse what seems real to him in flashes of projection. Richard at last asks Henry if he is happy. Henry replies, “not particularly . . . but you’re not very happy where you are, either.”

Richard’s lack of acceptance of his nature as an American and his inability to integrate his heritage into a living creative force has condemned him to the same hell as Henry, a constant awareness of greatness, of beauty, of nobility, but a failure to accept the burden of that legacy and build upon it. He is like those dead-souled bugmen who tear down the statues of their forefathers because they feel the burning reproach of their stone eyes. We reactionaries should always be mindful that what we seek is not the return of the past but the instantiation of greatness. We do not need British suits and pince-nez glasses- to be a Trad is not an affectation, not a look, but a mindset. We do not need to be Europeans to be the bearers of the Western tradition. I am American and can be nothing else. I am the inheritor of Greece and Rome. I am a poor steward of all of these things if I simply cling to what came before, or imagine the right way is the property of some continent or class of people. When Caesar comes, he will summon his legions in a familiar accent, from the places I know, from my people. I need look in no direction but around, and above.

For these reasons, I hold that The Secret History is the great American novel of the second half of the 20th century.

My heart nearly leapt out of my chest when I saw this! I love this book so much (Henry and Francis were objectively the best characters--fight me.)

Something I personally took away from the book was the apparent lack of connection between the kids and their parents. Richard's father was distant, Francis's mother shipped him off to boarding schools with fringe ideas, etc., etc. None of the kids knew what it was to have true parental love, leading to them being hyper-clingy around Morrow and hanging off his every word.

Not only that, but none of them knew how to handle their emotions--Henry meditated the murder of Bunny when he only deserved a punch in the chest, the others followed along due to peer pressure, Charles was abusive to Camilla, Camilla and Francis didn't know how to stand up for themselves, Richard did drugs, they all drank aggressively, etc.

While I haven't read this one, the descriptions of the characters and descent due to obsession remind me of the characters in Foucault's Pendulum - a collection of similarly odd esoteric history buffs and publishers too involved in their own mysteries to dig their way out