It’s been almost two months since the sad passing of Val Kilmer, and for some time now I’ve wanted to do a write up on one of his greatest films, 1993’s Tombstone. Certainly much has been said about the movie, a great Western in a period that produced a number of them- Young Guns (1988); Young Guns II (1990); Dances with Wolves (1990); Unforgiven (1990); and Geronimo: An American Legend (1993). But Tombstone was a unique offering compared to the rest.

The 1990s was a major period of revisionism in film, the original era of subverting expectations for a modern audience, as the Critical Drinker might say. Certainly the Westerns of the era challenged preconceived ideas about the genre. The Young Guns movies were less about gunfights than celebrity and the media construction of villains. Dances with Wolves was a somewhat maudlin and romanticized critique of western expansion. Unforgiven’s Will Munney was Clint Eastwood’s take on an over-the-hill version of his Spaghetti Western antiheroes, a broken man living in poverty, needing A Few Dollars More to feed his motherless kids. His antagonist- Gene Hackman’s Little Bill- is not only a killer of men, but illusions, and he spends as much time puncturing romantic notions about the Wild West and its violence as he does battling Munney.

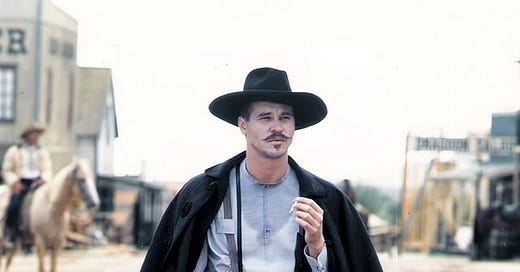

Remember when they made movies like this?

Tombstone is different. It’s not so much a Western- revisionist or otherwise- than it is a movie about Westerns. More specifically, it’s about the West as a mythogenic zone, and how the ancient traditions of Indo-European myth become, through art, transmuted into stories about America. It’s a powerful testament to the relevance of ancient tropes, which live on, quasi-consciously, in our creative spaces. Tombstone is not the movie that you think it is.

The film stars Kurt Russell as Wyatt Earp, joined by Kilmer’s Doc Holliday. But along with them comes a large ensemble cast of veteran actors, including Powers Boothe as Curly Bill Brocius, Michael Biehn as Johnny Ringo, Sam Elliott’s mustache as Virgil Earp, Bill Paxton (who is obviously going to die) as Morgan Earp, Dana Delany as Josephine Marcus, and Billy Zane as Gay Guy (not to be confused with Jason Priestly, who plays Other Gay Guy). In keeping with a trend at the time of having older Western actors return for minor (or even major) roles in revisionist 90s films- Jack Palance was in Young Guns and Geronimo featured not only Gene Hackman but Robert Duvall- Charleton Heston has a cameo as Henry Hooker. If the film has a weakness, it’s that with so much talent it becomes a challenge to give them all enough to do even in an already long film (watching it in class as part of a club activity, my students felt the third act was a bit rushed) and even a great director would have had a hard time managing everything. As it happens, though, it’s a bit unclear who actually directed it.

Seriously, Billy Zane should be in everything. He should have Pedro Pascal’s career. Also, this scene should be seamlessly edited into the Director’s Cut of Tombstone, and also Titanic.

The film opens, not with a sweeping vista of some forlorn grassland or clapboard frontier town, but with clips from other, older movies. These short scenes from early 20th century silent Westerns are interspersed with cleverly edited black-and-white footage of Russell and Kilmer in their Tombstone roles. The point is clear, to create conceptual overlap between the actual West and the West depicted in film- the West of myth- setting the stage for a movie that explicitly explores that idea. Earp as a main character is also a nod to that theme. The real life Wyatt Earp may have started his career as a cow-town lawman (and pimp) but he ended his days as a Hollywood consultant (admittedly, a step down from pimping) advising directors how to depict shootouts and such. John Ford himself said that he had a sketch from Earp’s own hand diagramming the Gunfight at the OK Corral, from which all subsequent depictions have drawn to one degree or another. Tombstone notes Earp’s personal importance in the development of the Western as a genre in the ending narration, stating that early silent stars William Hart and Tom Mix were pallbearers at his funeral in 1929. Earp was there for all of it, a living bridge between the history passing by and the stories being fashioned from it.

He wasn’t the only one. In the 1908 film The Bank Robbery you can see actual (former) outlaw Al Jennings and none other than legendary Comanche Chief Quanah Parker onscreen. Earp himself never acted.

While based on true events, Tombstone is heavily fictionalized, but more than simply having people and happenings shaped around a narrative, the fictionalization is really the point. The movie is less about the real-life individuals involved and more so about archetypes and themes. Unlike Kevin Costner’s Wyatt Earp of 1994, it is less a biopic and more purely a work of storytelling, Aeschylus rather than Spielberg. Thus, pointing out that Tombstone neglects the political backdrop to the actual disputes between the main parties, or that Earp had four brothers rather that the two depicted, or the complex legal maneuverings that resulted in Holliday ending up in a Colorado hospital misses the point.

It would take far more than a few thousand words to fully explore the range of mythological and Biblical themes and allusions in the film- the tarot cards, the scene from Faust as a play-within-the-play, the mention of Earp “walking on water,” etc. But certain tropes figure more than others. Broadly, all of the characters can be divided into one of three categories: monsters, men, and heroes. We meet the first group at the outset. The narrator (Robert Mitchum!) informs the viewer that a gang known as the Cowboys, driven from Texas, have spread through the frontier, the first example of organized crime in America. That certainly isn’t historically accurate, and in any case the film itself gainsays this by never really showing them committing actual routine crimes- apart, of course, from violence. Rather than spending their time robbing people or running protection rackets or pirating DVDs, the Cowboys seem only to show up to hurt people. They’re far worse than criminals. They’re monsters. They have no place in human society, even as thieves. None of them have homes or wives or children, or show any real interest in women or power or wealth. Like all unnatural beings, they prey on men for reasons of pure malign cruelty.

We see this in the opening scene. While the narration tells us they come from Texas, they seem instead an elemental force, riding out of the desert into a wedding at a church in Mexico. This too is significant. If the Puritans believed that the Indians in the wilderness beyond their borders were the Devil’s own subjects, then Mexico was Satan’s crown lands, where the hearts of thousands of victims were offered up to the dread old gods before Cortes and his grim conquistadors snuffed out those rites, slaughtered the priests, and burned their evil temples to ashes. But such dark forces are never really gone, as the continued existence of the Santa Muerte cult of the narcotrafficantes demonstrates, and such a haunted world will always generate new horrors.

The past is never really gone. It’s never even the past.

The Cowboys want revenge for the deaths of some of their number at the hands of some federales, one of whom is the groom. They murder him and his friends, then drag his bride into the church where she is assaulted and murdered offscreen. There is powerful symbolism in each of these acts. In Georges Dumezil’s trifunctional hypothesis, the gods of Indo-European myth were divided into three ‘functions,’ the first of which was sovereignty. This had a dual aspect, generally represented by pairs of divine leaders, one of whom symbolized authority as law and contract, the other spiritual power and binding magic. The Cowboys assault both, and take over the feast in the name of the monstrous anarchy they represent.

Driving home this point, Johnny Ringo, second in command under Curly Bill, casually guns down the officiating priest as he shouts imprecations at the gang. It’s clear that he’s something far more sinister than the others. While the other Cowboys are throwbacks to pagan lore, Ringo is wholly Satanic, a point emphasized throughout the film. In one scene, he offhandedly mentions that he’s sold his soul, in a way that even unnerves Curly Bill. He’s wise in ways that further set him apart; unlike the other gang members, he seems to grasp the spiritual dimensions of their depredations, and, demon that he is, immediately places the quote from Revelations the priest was shouting. It’s interesting that he’s not in charge of the gang, despite Curly Bill clearly being intimidated by him. One can posit that this is the film showing him as the motive force behind the monsters rather than their leader, the dark heart of the gang as opposed to its mind.

The federales, the priest, and the people of Tombstone are the men of the story (yes, some of the men are women). They represent the moving line of civilization, the frontier, bringing cosmic order to the wilderness, and thereby making enemies of the monsters infesting it. Their concerns are mundane and their lives small; they want peace and prosperity. On their own, they are powerless against the monsters, as their humanity makes them unable to grasp the full dimensions of the supernatural forces arrayed against them. They just want to grill, but the ogres won’t let them. But the cosmic order being what it is, wherever monsters appear, a hero is fated to come as well.

That hero is Wyatt Earp. True to American form, when he arrives in Tombstone, he at first expresses egalitarian sentiments, wishing to leave behind his career as a famous lawman and make money as a businessman. In short, he wants to be a man like everyone else. But the viewer quickly comes to understand that his true nature colors his approach even as he tries to flee from it. He acquires a stake in a saloon by manhandling a troublesome card dealer and strikes a careless railroad worker for abusing his horse. His instinctual response to injustice is violent redress, and his attempts to live like a man necessitate suppressing that urge.

Yes, Billy Bob Thornton is totally in this movie. He actually ad-libbed this whole scene.

Wyatt’s brothers join him. Themselves men, they instinctively look to him as the family leader, despite his being the middle son. But Earl’s closest relationship is clearly with Doc Holliday, who is also present in Tombstone. Holliday is the most complex character in the film and his relationship with Earp is the key dynamic in the narrative. But what is most interesting about him is that he, himself, is a monster. Like the Cowboys, he has no organic place in society. He roams from place to place, his trade unsavory, a killer and a gambler. He is doomed, cursed by consumption to die young, and like all monsters has no future, being defined by his relationship to a hero. Like Odin and Loki, Earp and Holliday share a kind of liminal connection, their friendship occurring at the further end of each side of a horseshoe, a place where it is possible for the bond between hero and monster to become less antagonistic than complementary. There is a sense, of course, where heroes and monsters have more in common with each other than either does with men; Aristotle famously noted that man is a political creature, and outside the polis are beasts and gods- things less and more than men.

The other monster in Earp’s life is another recent arrival in Tombstone. Josephine is an actress, an outsider to the world of men, a status reinforced by her unconventional sexuality and that of her companion. Unbound to the normalcy of the world of men, she is immediately attracted to Earp, fascinated by his nature, which, unlike hers, binds him to duty and violence on behalf of human society. She understands him to be among men but not of them, seeing that he will never be happy with the normal life he claims to want. Like her, he’s too much for the men around him.

Earp’s inherent nobility tames the selfish impulses of the monsters in his orbit, and they in turn give him the support he needs in the coming conflict. Holliday provides insight into the other monsters, particularly Johnny Ringo, who, in a masterful scene where they size each other up, is revealed to be a kind of dark mirror to himself- educated, violent, and distinct from his companions in a way they find alienating. It’s Holliday’s friendship with Earp that differentiates them and redeems Holliday, just as the raw authenticity of his being gives focus to Josephine in a world she’s otherwise inclined to flit through carelessly. In a way, he’s closer to them than his own brothers, who for all their courage and honor remain, in the end, men.

This clip is legendary, from Beihn’s real-life pistol skills to the exchange of Latin tags that still inspires Classics teachers.

The conflict between the Earps and the Cowboys is inevitable, despite Wyatt’s attempts to avoid it. His nature as a hero compels him to intervene when a hopped-up Curly Bill shoots elderly town marshal Fred White (played by longtime John Ford collaborator Harry Carey Jr.). Springing into action on his own initiative, he subdues Curly Bill and stares down both the rest of the Cowboys and an incipient lynch mob. Despite Curly Bill not being charged with the crime, it is clear that a battle is brewing, with the other Earp brothers accepting commissions as lawmen against Wyatt’s advice to stay out of things. Holliday, for his part- and true to his monstrous nature- is uninterested in peace and actually stirs up trouble at a card game with Cowboy Clanton brothers, especially the unstable but cowardly Ike (Stephen Lang is hilariously unlikable).

My students react the same way when I suggest a spelling contest.

This leads to the famous gunfight at the OK Corral, which results in the deaths of several Cowboys. A subsequent series of revenge attacks on the Earps cripples Virgil and leaves Morgan mortally wounded (Bill Paxton was never going to make it). Earp leads the survivors out of town, stopping to inform the Cowboys of his acceptance of their victory. Curly Bill quickly becomes a meme before sending gang members Frank Stilwell and Ike (for some reason) to ambush and finish off the defeated Earps.

It’s a movie that launched a thousand gifs.

But Earp is not deceived, and turns the tables, killing Stilwell and maiming Ike. Earp now has a posse, not of men, but alongside Holliday, other monsters- desperadoes linked to him through his past as a gunman, alongside Cowboys renouncing the evil of their past lives and seeking redemption. This scene represents the moment when Earp finally accepts his mantle as a hero, resigned at last to ridding his society of the unnatural predators that plague it. It’s easy to miss, but it’s all a callback to the beginning, with Earp donning the badge of a lawman while simultaneously referencing the same verse from Revelations as the fallen priest. Evola theorized that at its earliest stages the authority of priest and king were united in one person; here we see that unity of those Dumezilian functions into Earp. His mission is both legal and spiritual- cosmic really. As usual, Holliday understands, explaining to the others that what Earp seeks is not revenge, but a reckoning. His mission is to set right the order of the universe within the scope available to him. And this means a lot of killing.

Earp shoots Curly Bill in a gunfight in a creek, but this merely clears the way for the ascent of Johnny Ringo, the ultimate source of the spiritual pollution in their midst. Holliday, seemingly laid low by the tuberculosis that is inexorably killing him, again offers his insight, explaining to Earp that Ringo’s rage, like that of Satan, is against existence itself. Earp finds himself at a moral precipice, seemingly facing a foe that can’t really be destroyed, not without lowering himself into becoming like him, trapping himself in this dark world, away from Josephine, whom he now realizes he wants, but could never have so long as he follows this path. And here the narrative again demonstrates the manner in which Tombstone is a mythological and spiritual film. Holliday, merely feigning incapacity, takes up the burden of facing Ringo on his friend’s behalf, knowing that his sacrifice will unburden Earp of what would surely be a mission of no return. Ringo- seemingly understanding the import of Holliday’s appearance, is shocked for the first time. Holliday kills him, but Ringo’s death was less the result of lead than love, of Holliday’s vicarious adoption of Earp’s duty as a hero, saving his life and his soul.

Quick work is made of the remainder of the gang, and the movie then transitions to its most moving scene. Holliday lies dying in a Colorado sanatorium, visited by Earp. He declines to gamble anymore, preferring to tell Earp of his youth, and the great love of his life, who joined a convent as a result of the scandal involved. He is converting to Catholicism, symbolically joining her as well as making explicit his journey from being a monster. But there is one final redemptive act. Holliday makes it clear that Earp will have to leave him behind forever- not after his death, but immediately. Like Earp, he once wanted a normal life, but realized that it was never to be, for him or Earp, and that his only path to peace is to make his own way. He must choose, now, to renounce the world of monsters and violence for a life with Josephine, accepting that he has earned the right at last, like Hercules, to rest from his labors. Earp leaves him with a book, his mighty deeds recorded like those of the aristoi of Homer. Holliday has been transfigured from monster to hero. And in a final nod to his Christian journey, he looks down to see his bare feet peaking out from the blankets. No violent “dying with his boots on” for him. He has, like his friend, earned a peaceful repose at last, his sins forgiven.

The final scene takes us full circle. Earp, now back within the bounds of civilization, finds Josephine and tells her that he is at last stripped of everything from his old life. Thus purified, he can now be at peace, not to live as a man, but as a new type of hero, a living presence from a disappearing world, a man who remembers, who can tell others of the great deeds of old. He was there. And long after all the rest were gone, Wyatt Earp could shape the very soul of his civilization, not with his now-silent guns, but with his words. Like the heroes of old, he experienced a kind of apotheosis, becoming less a man than a living myth. He lives on still.

You know you’re a legend when there’s a Wikipedia page solely dedicated to your righteous vengeance. It’s something to which we can all aspire.

The West is the American Dreamscape, a great swirling Ginnungagap from which stories emerge unbidden into our imaginations. Tombstone is a movie about that place, the West that inspires and haunts us, the place we must search out to know who we are. It’s a philosophical and meditative piece cleverly disguised as a well-crafted Western, much as Predator seemed like an sci-fi action thriller. And of course, it’s one of the late and legendary Val Kilmer’s greatest roles. RIP, you earned it.

For those who were asking, I’ve added a “Buy Me A Coffee” option. Thank you all for your kind patronage.

One of my favorite westerns. My best friend says he's the Doc to my Earp in the scene where Doc is asked why he's doing all this.

"Wyatt Earp is my friend."

"Hell, I've got lots of friends."

"I don't."

It has long been rumored in scientific journals that Sam Elliot's mustache has its own gravitational field.

Excellent article, I enjoyed it as my evening read.