[This essay is many things- a continuation of my series on the lives and works of the great mythographers, a deeper dive into Classicism, more Floridapoasting, more still on education, and primarily what I hope will be an interesting look and an often overlooked figure from the past, a man with the somewhat drossy good fortune to live in a time and place filled with genius.]

Giovanni Boccaccio could never be the sun, only a star in a firmament studded with them, and was further outshone by two nearer celestial giants, Dante Alighieri and Francesco Petrarca. Dante was perhaps the most profoundly theological artist the Western world has ever known, creating with ink the like of Michelangelo’s work in paint and stone. Petrarch was the great resurrectionist, the hierophant who revealed the mysteries of the Classical world to Christian Europe, breathing new life into the creative spirit of his people. Boccaccio was nothing so ambitious. His works are brilliant, the product of a deep and wide ranging intelligence and creativity, but they are so human in their scale that they are simply outclassed by those of the other two Crowns of Italian Literature. To put this in terms that a modern audience can relate to, he was like Batman in the Justice League, a superior man in a conclave of demigods, unable to come into his own by comparison, but amazing in his own right. Geoffrey Chaucer, his contemporary and admirer, is the best analogue. Chaucer, who was greatly influenced by Boccaccio and may have met him, gets his due because the English Dante and Petrarch- Milton and Shakespeare- came centuries later.

Boccaccio is best known today for his great masterpiece, The Decameron (The Ten Days)- more on that to follow. He is also important as a writer for his lesser known Genealogia deorum gentilium (Genealogy of the Pagan Gods), which is one of the earliest Medieval compendiums of pre-Christian myth (apart from Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda)- more on that to follow as well. He is worth reading for either of those. But one of the things that makes Boccaccio so approachable, arguably even more so than Petrarch- who actively worked to make himself approachable- is how strikingly modern of a figure he presents from a distance of nearly seven centuries.

Boccaccio was born in 1313 into a middle class family living in a suburb of Florence called Certaldo. Family is perhaps not the right word; his father was not married to his mother, who is nameless to history. Banking was the family trade and Boccaccio’s father expected his illegitimate son to follow him into it, but it seems that young Boccaccio had a rebellious streak and hated the idea of a dull desk job. He convinced his father he would make a better lawyer than a banker, which was mostly a pretext to get away from home to go to college in distant Naples.

Certaldo is the New Jersey to Florence’s New York.

The University of Naples has a claim to being the oldest institution of higher education in continuous operation in the world, though this is disputed. It was founded in 1224 by the cultured renegade Emperor Frederick II Hohenstauffen, a man who spent as much time excommunicated as he did within the Church’s good graces, fond of quoting the Quran and Epicurean philosophy in equal measure. The university, however, was not consciously a countercultural project- rather, college then was like college now, a place to train administrators for the system with appropriate job skills and a patina of liberal education to impress those over whom they administered. The idea of the university as a hub of humane learning and the life of the mind had yet to come, and in fact would owe much to Boccaccio and his generation. They were the Christian humanists, schooled in both the doctrines of the Church and the wisdom of their pagan forbears, the two forces producing an enormous creative tension. The progress of this ideal was helped greatly by Robert the Wise of Naples, a scholar-king with a brilliant second wife who was fully committed to defending Italy from encroaching northern political control and the revival of culture for the shared purpose of ending what Petrarch had coined as the Dark Ages. This is key to understanding Boccaccio and his world. He, like those of us who venerate Tradition, saw the world around him as encumbered by a weary and ignorant decadence, and sought, through his own efforts, the reinvigoration of cultural life through the vital sources he knew were the only authentic wells on which to draw, Christianity and Classical learning. This is not to say they were always devout, or that they fully embraced the ideals of pagan Rome and Athens; a revival in the truest sense is new life, something midwifed into the world with both ancestors and a future. This rebirth would one day enter into full bloom as the Renaissance, with effects both beneficial and malign.

A bit later than Boccaccio’s era but basically the same outlines.

It was in Naples that Boccaccio met his muse, Maria d’Aquino, an illegitimate daughter of King Robert himself. Unlike the pure Beatrice of Dante and the stately and remote Laura of Petrarch, Maria, known to Boccaccio as Fiammetta (little flame), was a genuine bad girl, for whom marriage and noble status served as no barrier to an active social life. There was certainly nothing courtly about their very physical romance (at least as he told it). Of course he wrote a poem about it; speaking in her voice he writes:

“But how dear to him was my own apartment, and with what gladness did it see him enter! Yet was he filled with more reverence for it than he ever had been for a sacred temple, and this I could at all times easily discern. Woe is me! What burning kisses, what tender embraces, what delicious moments we had there!”

Fiammetta was later involved in a murder plot and executed by beheading. By then, however, Boccaccio had moved back home.

Florence in the late 1330s and early 1340s was a city bursting at the seams with money and energy, but also tension. A populist revolt had sidelined many of the city’s traditional elites, the merchants and bankers who controlled the economic and political life there, which is to say, Boccaccio’s class. But nothing was as clear-cut as that. Boccaccio was in a strange situation, all things considered. He was a Florentine, but not quite- his suburban upbringing and years living away from home meant that he would have felt like something of an outsider. There was also his unstable family situation. His mother, if he had even known her, was certainly dead by this point. His father had gone bankrupt, remarried, and started a new family while Boccaccio had been off at college. Life must have seemed quite chaotic and insecure even in the midst of the relative abundance of one of the wealthiest and proudest medieval cities.

One hesitates to call Boccaccio a Gen-Xer avant la lettre, but there are some parallels. There is his crumbling facsimile of a nuclear family, his suburban orbiting of high culture, his college education preparing him for an unwanted job that didn’t await him in any case, and above all, a desperate longing for authenticity, a drive to the root of things, an escape from the world of managerialism into art for art’s sake, leavened by a sense of jaded irony and emotional distance from things that really did matter to him. He’s not quite Kurt Cobain, or to continue our established parallel, Robert Pattinson’s Batman, but something of that ethos is there. Boccaccio was to produce some excellent early work during this period, his Ameto, his Amorosa Visione, and his aforementioned Fiammetta. These works, significantly, continued along the path forged by Dante and Petrarch in being written in the vernacular, in their shared Toscano language, that would, thanks to their combined efforts, eventually become the standard Italian of the future nation. He was of course able to write just as well in Latin and various other languages of the Italian peninsula, and later in life actively pursued the study of Greek, working with Barlaam of Calabria, that temperamental Byzantine humanist turned heresiarch, on translations of material from the Classical world.

But before that came the event that would define the entire High Middle Ages in the period before it shaded into the Early Renaissance, the Black Death of 1348-1352. It is impossible to exaggerate the scale of this catastrophe; at a stroke, Europe lost a third of its population. Florence was near the epicenter of the outbreak and suffered worse than most places, losing some 60% of its citizens to the Black Death. Boccaccio was probably there for at least some of it, though it seems he spent the majority of the four deadly years in his familiar suburb of Certaldo. It nonetheless had a profound effect on him, as would be expected.

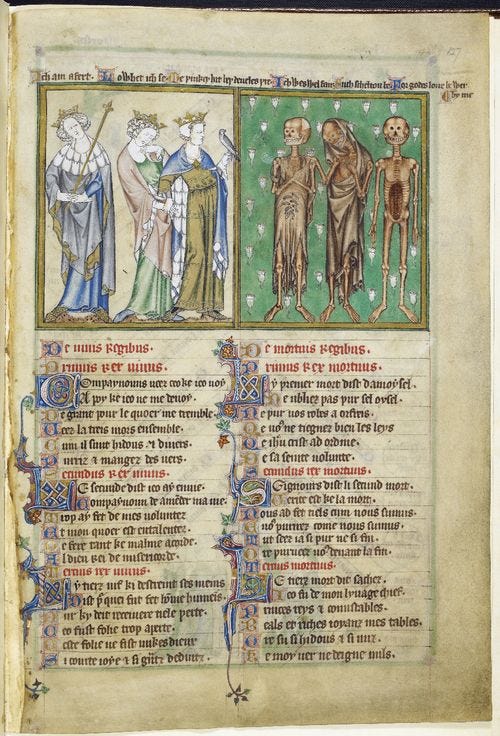

“As you are, so were we; as we are, so shall you be.”

It is not clear exactly when he began working on his magnum opus, The Decameron, but the work is impossible to imagine without the impetus of the Plague, both in terms of the influence on the author and as a framing narrative. The Decameron is innovative for many reasons, but most significantly it has a contemporary setting, avoiding the sometimes forced archaism common to medieval literature. It’s not the Trojan War imagined with knights and castles, but the world Boccaccio knew from daily life, or in this case, daily death. It would not be farfetched to describe it as the first post-apocalyptic fantasy. You may recall this excerpt from high school world literature, the first and last time most people encounter the medieval humanists:

“. . . Either because of the influence of heavenly bodies or because of God's just wrath as a punishment to mortals for our wicked deeds, the pestilence, originating some years earlier in the East, killed an infinite number of people as it spread relentlessly from one place to another until finally it had stretched its miserable length all over the West. And against this pestilence no human wisdom or foresight was of any avail; quantities of filth were removed from the city by officials charged with the task; the entry of any sick person into the city was prohibited; and many directives were issued concerning the maintenance of good health. Nor were the humble supplications rendered not once, but many times, by the pious to God, through public processions or by other means, in any way efficacious.

. . . Neither a doctor's advice nor the strength of medicine could do anything to cure this illness; on the contrary, either the nature of the illness was such that it afforded no cure, or else the doctors were so ignorant that they did not recognize its cause and, as a result, could not prescribe the proper remedy (in fact, the number of doctors, other than the well-trained, was increased by a large number of men and women who had never had any medical training); at any rate, few of the sick were ever cured, and almost all died after the third day of the appearance of the previously described symptoms (some sooner, others later), and most of them died without fever or any other side effects.

. . . There were some people who thought that living moderately and avoiding any excess might help a great deal in resisting this disease, and so they gathered in small groups and lived entirely apart from everyone else. They shut themselves up in those houses where there were no sick people and where one could live well by eating the most delicate of foods an drinking the finest of wines (doing so always in moderation), allowing no one to speak about or listen to anything said about the sick and dead outside; these people lived, entertaining themselves with music and other pleasures that they could arrange. Others thought the opposite: they believed that drinking excessively, enjoying life, going about singing and celebrating, satisfying in every way the appetites as best one could, laughing, and making light of everything that happened was the best medicine for such a disease; so they practiced to the fullest what they believed by going from one tavern to another all day and night, drinking to excess; and they would often make merry in private homes, doing everything that pleased or amused them the most. This they were able to do easily, for everyone felt he was doomed to die and, as a result, abandoned his property, so that most of the houses had become common property, and any stranger who came upon them used them as if her were their rightful owner…

Many others adopted a middle course between the two attitudes just described: neither did they restrict their food or drink so much as the first group nor did they fall into such dissoluteness and drunkenness as the second; rather, they satisfied their appetites to a moderate degree. They did not shut themselves up, but went around carrying in their hands flowers, or sweet-smelling herbs, or various kinds of spices; and they would often put these things to their noses, believing that such smells were a wonderful means of purifying the brain, for all the air seemed infected with the stench of dead bodies, sickness, and medicines…

And not all those who adopted these diverse opinions died, nor did they all escape with their lives; on the contrary, many of those who thought this way were falling sick everywhere…brother abandoned brother, uncle abandoned nephew, sister left brother, and very often wife abandoned husband, and – even worse, almost unbelievable – fathers and mothers neglected to tend and care for their children as if they were not their own..

Many ended their lives in the public streets, during the day or at night, while many others who died in their homes were discovered dead by their neighbors only by the smell of their decomposing bodies. The city was full of corpses…Moreover, the dead were honored with no tears or candles or funeral mourners; in fact, things had reached such a point that the people who died were cared for as we care for goats today…So many corpses would arrive in front of a church every day and at every hour that the amount of holy ground for burials was certainly insufficient for the ancient custom of giving each body its individual place; when all the graves were full, huge trenches were dug in all of the cemeteries of the churches and into them the new arrivals were dumped by the hundreds; and they were packed in there with dirt, one on top of another, like a ship's cargo, until the trench was filled…

What more can one say except that so great was the cruelty of Heaven, and, perhaps, also that of man, that from March to July of the same year, between the fury of the pestiferous sickness and the fact that many of the sick were badly treated or abandoned in need because of the fear that the healthy had, more than one hundred thousand human beings are believed to have lost their lives for certain inside the walls of the city of Florence – whereas before the deadly plague, one would not even have estimated there were actually that many people dwelling in the city.”

The Plague represented the ultimate possible failure of the system at all levels to work as people believed it would. The medicine of the doctors and the prayers of the bishops were of no avail to end the sickness; God’s judgment was being rendered on the sinful world that had forgotten Him in its pride and excess. In our own times we of course have the fake and ghey version of this, a spurious epidemic that our new clergy failed to convincingly pretend to alleviate, but agree among themselves that such was their success that the public fully backs them in launching a new round of pointless wars, this time against enemies stronger than those who now rule in the lands where we last fought. It would be as if there had been no Black Death, but the various kings of Europe had collectively told their peasants to stay in their hovels for four years anyway, and when a third of them starved to death, proclaimed a success and a new crusade against the Mongol Empire.

Boccaccio’s story serves as the framing device for an anthology of stories. The Decameron is impossible to summarize as a whole, but the central plot involves ten friends (three young men and seven young women) who encounter each other after an empty Florentine church service one Sunday during the Plague. Their civilization has utterly collapsed and they are faced with what many in their age reckoned were the end times. In our own age this would have been the beginning of a Walking Dead type of story with grim survivors grimly grimming their way across a zombie-strewn grimscape. Boccaccio’s protagonists hit upon a different idea; they will retreat to the countryside and wait out the worst of it while telling stories to pass the time. Each day’s storytelling will have a different theme, and each person is to tell a story each day. The sheer range of the stories is astonishing, everything from somber tragedy to near-pornographic humor, and the book as a whole is a testament to the vast cultural inventory of medieval life. What seemed plausible as a narrative device would strain credulity today; how many people do you know who could relate an interesting tale on command for ten straight days? Does that person have nine friends? Could any of them do that?

There is much to learn here. Of all the possible responses to catastrophe that Boccaccio relates in his introduction, the one he endorses, the one to which we should pay heed, is the one that serves to bring together the tales of The Decameron. The catastrophe of our age is (for now) slow moving and perceptible only to those with eyes to see, but is there nonetheless. We too must draw on the inner strength of our faith and culture, rediscover and revitalize traditional forms as our ancestors did. The groundwork laid by Boccaccio and his peers formed the basis for the great Florentine golden age that itself served as the foundation of the Renaissance. And though that great movement veered off into secularism and schism there was nothing forgone about that conclusion, and even then, the good outweighed the bad.

It is also important to bear in mind as well that Boccaccio, a writer of the highest caliber, had a day job. Like the Gen-Xers to come, he sold out and went into working world, taking up the family mantle of civic responsibility. He went on important missions for Florence and performed a number of government jobs, including welcoming Petrarch to the city, beginning a great and influential friendship. But he was never fully free to pursue his art, a fact true of nearly every artist then and up to the present. Consider that greats like Brunelleschi and Michelangelo were businessmen working on commissions; their time spent managing staff and studios must have far outweighed their time with brush and chisel. Even profoundly prolific writers like C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien were employed full-time as professors and had all the demands of family life (weirdly in Lewis’s case) as well. Let this be a lesson to those of us who would be artists if we had more time; we always have time to do the things that are important to us. The habits of industry and discipline mean as much as imagination and creativity.

Along those lines, Boccaccio further pursued a number of scholarly endeavors on top of his poetry and fiction. Most notable among these was the Genealogia deorum gentilium,his genealogy of the pagan gods of Classical antiquity which he worked on for the last fourteen years of his life. This work served as the go-to resource for Renaissance artists looking for tropes and symbols with which to adorn their works, and was a standard reference work until the end of that period (Boccaccio pioneered the use of the ‘family tree’ model of illustration). In addition to being an important mythographer, Boccaccio also wrote a great amount of biographical literature- his most famous being the De mulieribus claris (lives of famous women). This and other artistic labors consumed his final years. Though he always remained somewhat jaded by life, he became increasingly more devout as he aged- certainly under the influence of Petrarch- and when he passed away at the age of 62, it was as a man of faith.

In closing, I would ask the question: how much did the place make the man? Could we have his life without his world? I think in some sense the setting is part of the artist. But then, Boccaccio was not merely a man of his time, but a man who through a will to excellence made his time what it was. Did this in part require new and insecure money, a climate tolerant of innovation, education and some form of cultured ease? Certainly, but are not those things available in our own day and age? To give but one example, you readers have perhaps seen the Florida is the New Rome’ meme? If not, here it is:

I like this anon’s energy, but I think his analogy is just a hair off. Florida is not the new Rome; it is not bursting with violent energy and surrounded by conquerable tribal enemies like the Republic, nor is it a great and decadent empire. Florida is the Nova Florentia, the new flower of our age, full of sunshine, rich people, a dynamic tension born of religious sensibilities and cultural ferment, and above all a place aching for a connection to authentic tradition, a sure foundation for artistic greatness. I think that Florida, above all places in not only the US but the West as a whole, is perfectly poised to become what Florence was in the Middle Ages. Let us hope that wise leadership and creative souls discover this.

"There is his crumbling facsimile of a nuclear family, his suburban orbiting of high culture, his college education preparing him for an unwanted job that didn’t await him in any case, and above all, a desperate longing for authenticity, a drive to the root of things, an escape from the world of managerialism into art for art’s sake, leavened by a sense of jaded irony and emotional distance from things that really did matter to him."

Wow. I can't believe it, but... dare I say it... he really is literally me, fr fr. This is a great primer to introduce a criminally underrated figure, and I only say that as someone who is dully aware of his importance to the Italian language and Chaucer (I studied a lot of British literature, so his name came up when we studied Chaucer, but that was about as far as it went). You've done a great job at illustrating just how influential he is, as well as painting some very vivid and impressive parallels between his time and our own. I have often thought it myself, albeit in different terms - a decadent and debased world, miserably unprepared for the catastrophe we sit on the cusp of.

What do you think of the nature of evil? I was watching The Exorcist I & II last night and we got to discussing demons and the devil - and the nature of evil. Many of the evils of Boccaccio's time - the black death being paramount - we seem to have overcome with sanitation and understanding of germs and the microscopic world.

To me it seems this science - that has saved us for well over a century from Cholera, Typhus, etc. - yet always subject to perversion and bad application - is now being fully perverted to a utopian fantasy that may wreck us all. Surely the work of the devil - of manifest evil - if ever there was.

Some say the devil is the evil that men do. Or is it a force unto itself that travels here and there, lurking, waiting and finding its opportunities to wreak havoc on humanity?

What do scholars like Boccaccio say?