Edith Hamilton, Headmistress of the Bryn Mawr School

I turned six years old in 1985. It was already clear that I was going to be a reader, and my parents, working-class people with but a single completed high school education between them, worked hard to make it possible for me to do so. Some of my earliest memories are of my mom teaching me my letters and my dad reading to my sister and I after his ten-hour days as a machinist. We were not a literate or artistic family by any means, but my parents sensed that their children could benefit from things they themselves had no interest in. My youth was therefor filled with books, though there was always room for more. And so it was that for my sixth birthday my paternal grandmother took me out to Waldenbooks.

Do you remember this place? It was there but a moment ago, and yet it’s been so long . . .

It’s impossible to convey the sense of wonder a pre-internet bookstore could elicit. You couldn’t have any idea what was out there in the written world until you walked in and saw the shelves. Like the library, it was a zone where ideas mattered, and though I knew little about money at six I knew that adults traded it for things that were important to them; seeing the grown-ups handing over their dollars for books made a distinct impression on me. My grandmother, like my parents, was not an educated woman. She raised five sons largely alone in Florida on a waitress’ salary. She was a reader of sorts- I distinctly remember the Fabio-adorned covers of the bodice-rippers she favored. But to my knowledge she was not in any sense interested in what professors would call literature, and being older had only a vague sense of what a child would want to read. We bought some Hardy Boys novels and some other things I can’t recall. But then, the precise moment lost to me, I chanced upon the book that would change my life.

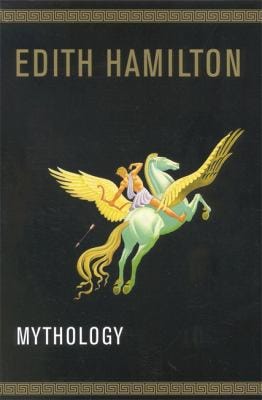

Edith Hamilton’s Mythology had a Pegasus on the cover. That is no doubt what drew my attention and why I insisted I had to have it. I had seen Clash of the Titans at that point and anything that reminded me of that glorious Ray Harryhausen stop-motion classic got an automatic green light as far as I was concerned. Grandma duly bought it; it was a cheap paperback after all. Had she known exactly what it was she might have hesitated. It was not a children’s’ book, being intended for an adult audience assumed to have a good bit of education behind them. I tried to read it and was at a loss. I tried again and again. The illustrations were what kept me going, beautiful art-deco inspired designs in heavily-inked black and white, so different from the colorful world of my kids’ books. After some years I began to assimilate the material without really comprehending it. After some more years I knew the stories backwards and forwards. By high school I knew enough about myth to pick out allusions in English class. By the time I went to college I was reading the authors Hamilton had referenced; by the time I (more-or-less) finished college I was reading them in the original Greek and Latin. That dog-eared and coverless paperback edition of Mythology currently sits wrapped in leather under the base of the lamp on my desk in my classroom, the foundation of my illumination.

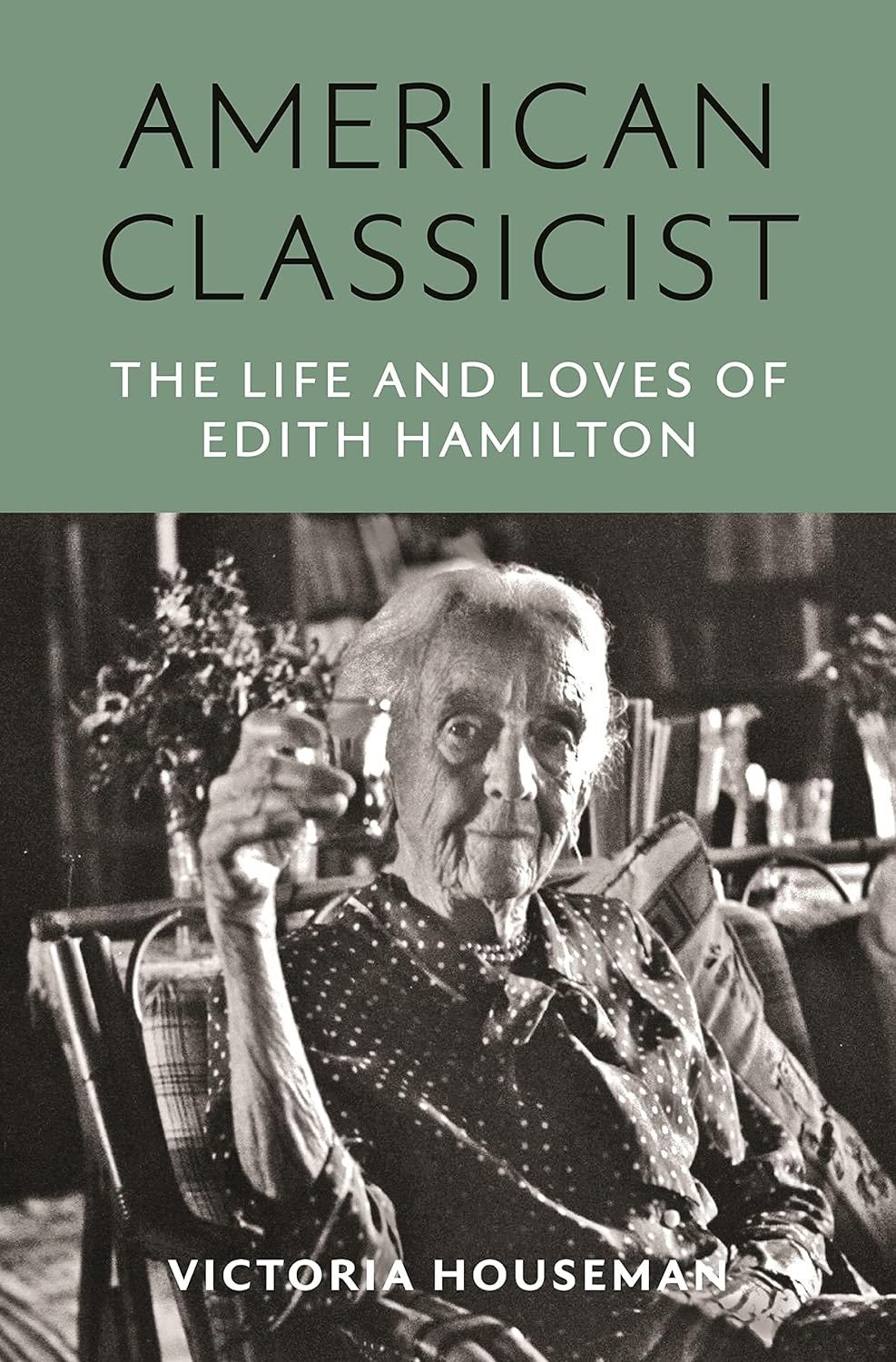

It was thus with great interest that I learned last month that a biography of Edith Hamilton, by Victoria Houseman, was forthcoming. I preordered it on October 2nd; it arrived on the 4th, and I finished it just yesterday. I had previously read the only other biography of Hamilton, written by her . . . companion Doris Reid (more on that below), but while interesting, that text was more of a personal tribute than a scholarly investigation. Hamilton has been sadly neglected by scholars since her death in 1963 at the age of 95. In her day, she was an internationally-known writer of popular non-fiction works dealing with the Classical world, and to a lesser extent, early Judaism and Christianity. More than anyone else in the twentieth century she was responsible for popularizing the study of the Classics, and especially for making the great body of Greek and Roman myth approachable for a modern audience. Her Mythology, the one I encountered in my suburban bookstore, remains the single best introduction to the subject in English, and as far as I know, in any language. She is one of the great mythographers of the past two centuries, a figure as important as Dumezil or Gimbutas or Eliade (whom she knew) or any other of the like, but is rarely given her due. Why this is, and where the Houseman biography fits in terms of understanding her legacy, is a matter that calls for some explaining. In doing so, there are important lessons we can learn about both the past and the future of Classical studies and Western Civilization.

Edith Hamilton was born in 1867 in Fort Wayne, Indiana, then a small town settled largely by Yankees in the preceding few decades. Her grandfather had actually owned most of the land that became the core of the town, and she grew up in a large, middle class home on a large acreage in the center. She had three sisters and one brother, who came about much later. Hamilton’s parents were educated and cultured people and she grew up in the midst of a great number of friends and cousins with whom she would continue to be close throughout her life. Her childhood, in post-Civil War America, was in many ways better than others could hope to enjoy before or since. Her parents hated the nascent public school system, regarding the curriculum as inferior, so she and her sisters were tutored at home, both by their parents and specialized teachers hired for the purpose. She began Latin at seven and Greek shortly after; her mother taught her French and tutors from the local Lutheran church provided instruction in German. Much of her time was spent in the extensive family library, reading with her sisters, sharpening each others’ wits with books meant for those much older.

Nothing is perfect, however, and there were problems beneath the surface. Hamilton’s father had grown up in relative wealth and lacked the emotional resilience to handle business setbacks; after some bad turns during Hamilton’s teen years the family finances were strained and it became clear that young Edith would have to support herself as an adult. One might have expected that she would marry into a family of similar status, but that never seems to have been a serious option. None of the Hamilton sisters would ever wed. They were too unique, too close knit, and too independent to live conventional lives. There were other factors as well. There seems to have been a streak of madness in the family; much like the Wittgenstein siblings, the Hamiltons struggled with depression, though unlike the former, it was not taken as far as suicide. Reid, but oddly not Houseman, details Hamilton’s stormy moods as a young woman, her tendency to melancholy and her feelings of alienation. For a woman who would dedicate her life to Western Civilization and to the 4th Century BC Athenians, with their keen sense of place and belonging, Hamilton was strangely rootless throughout her life, living in many places but not really of any of them.

“As for her face, it seemed too maidenly to be that of a boy, and too boyish to be that of a maiden"- Hamilton on Atalanta, Mythology.

The first of those places was the all-girls Miss Porter’s School in Connecticut, the two years she spent there being the only formal schooling she would have before college. There she was initiated into a world of intense emotional relationships with other women which was then apparently the norm at such institutions. It would be an anachronism to speak of Hamilton as a lesbian in the modern sense. She never, in the entire course of her life, wrote or spoke about any intimate details about her relationships with women, and it is unclear if she was ever physically involved with another human being. Houseman uses the phrase “platonic” to describe her various relationships. It was clear, however, that the women at the school- the students, the teachers, and the students and teachers- formed bonds with each other that were clearly romantic. Houseman, and everyone else who wrote about Hamilton, misses a clear point of comparison that I expected would be fully elaborated upon: Hamilton was not a lesbian, but a Lesbian. She was in a very real sense a modern version of Sappho.

Sappho remains the only woman writer of any significance from the Classical world whose work is extant, a poetess from the Island of Lesbos (yes, that’s where the name comes from). Little is known of her life for certain, but it seems she had some role in instructing younger ladies in some ritual context. Her poetry, surviving mainly in fragments, details her intense bonds with these young women, and her feelings of loss when they were married off to men. It is unlikely that she herself was married, which would have been unusual in the world of the Ancient Greeks, and yet those same Greeks regarded her, universally, as a poet of special holiness, one of the great figures of their civilization. In like manner, the world of girls’ boarding schools and colleges in the 19th and early 20th centuries seems to have been one of similar sorts of relationships, a theme seen in Picnic at Hanging Rock, among other works. The girls would enter a period of life when same-sex emotional bonds were a given, and then, one day, they would leave them behind for men. There never seems to have been any sense that an inclination toward women should be understood to be inborn or permanent, even when, as in Hamilton’s case, it proved to be so.

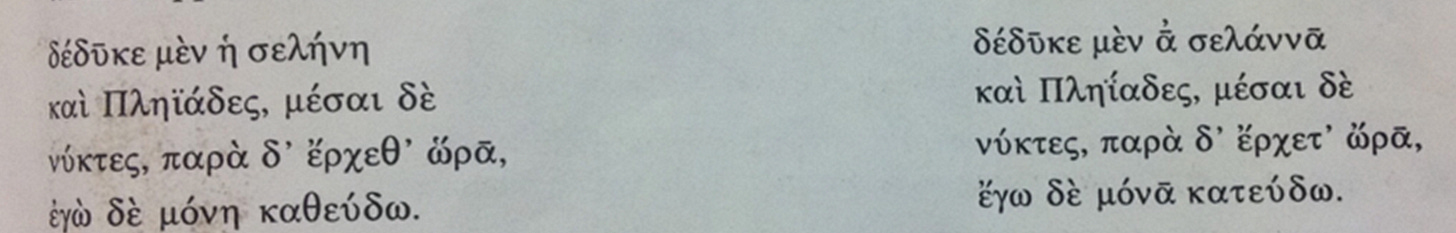

The Moon has gone down in the heavens,

The Pleiades have come in the midst of the night,

All the while I sit alone,

Alone, as time passes by.

-Translation is mine

Throughout her life Hamilton would live with female companions in ways that were clearly domestic arrangements, the most remarkable thing about them being that no one remarked upon them. As we will see, Hamilton mixed with a staggeringly diverse array of several generations’ worth of writers and public figures, and none of them ever seemed to find it interesting or significant that Hamilton lived as she did. It must also be remembered that Hamilton grew up in an extremely demographically lopsided world; the Civil War had annihilated 700,000 of the nation’s husbands and eligible bachelors in the previous generation (the period was also the heyday of the Mormon “plural marriage”). Perhaps people just sort of winked and nodded at the “Boston marriages” that were, in some cases, the necessary practical recourse of women unable to find men, granting the same deference to women uninterested in doing so.

Cartman has theories.

After hard study, Hamilton entered Bryn Mawr College in 1891, another all-female world. She completed her BA and MA at the same time, after only three years of study, and won a scholarship to study in Germany. There she encountered the world of academic Classics, then as now an insular and forbiddingly weird place, where she found the contemporary emphasis on philology off-putting and sterile. Putting her desire for a PhD and an academic career aside, she accepted a job as headmistress at the Bryn Mawr School, a feeder for the college, located in Baltimore. Unlike today, where fossilized boomers cling to jobs from beyond the grave, it was felt at the time that youth, energy and imagination were needed to run schools; Hamilton, as the new headmistress, was less than a decade older than some of her charges. She would stay at the school for her entire normie career, some twenty-six years. During that time she guided the school from near failure to being a local institution, upholding demanding academic standards for girls from a social class that generally thought a few years of polish were all that was needed for a debut and a profitable marriage. The final exam for graduation was the entrance exam for Bryn Mawr College, and by modern standards it was brutal, a blend of Classical texts and high-level math that would have today’s girls and boys screaming for their Xanax. That she was able to maintain that standard throughout her tenure, in the face of progressive attacks on the Classics and families who looked askance at their daughters failing out of high school for not being able to decline Θεμῐστοκλῆς, is a testament to her will and powers of persuasion. Throughout her life, from childhood to the very end, she believed in Classics as a civilizing force, the motive power of the West.

This basic proposition colored her entire worldview, social, political, and religious. Hamilton was more or less a lifelong progressive Republican and a Social Gospel Protestant, believing always in a kind of creedless Christianity instantiated in liberal political forms, the aim being to uplift mankind into an ever-greater awareness of both individual potential (self-actualization in Dewey-speak) and social concern. She was heavily influenced in her youth by Matthew Arnold and Edward Caird. Her outlook, patriotic but cosmopolitan, romantic in temperament while accepting of modernity, and possessed of the confidence that her culture was meant as a light unto the world, was reminiscent of contemporaries like Theodore Roosevelt and Douglas MacArthur. But unlike with those men, hers was a philosophy very informed by her consciousness of being female and by a fixed hatred of violence in any form. In her youth she advocated for women’s suffrage, and in her later years would espouse anti-imperialism, isolationism, and pacifism. However, much like with her rootlessness, there was a timelessness to Hamilton that made her hard to categorize in strict terms politically. If anything, her life philosophy was a sui generis approximation of what she took to be the basic outlook of a well-bred Athenian, circa 450 BC. Her connection to that tradition meant everything to her. Far from being an object of study, the Classical world was a model for human life, hers in particular. Unlike the later generation of capital-P Progressives who were largely secular and technocratic, Hamilton felt that without the Classics and the Gospels, humanity would wither into gray misery. Though she knew and admired John Dewey, she felt that his rejection of the Classics for modern and technical subjects was shortsighted and reductive. Some of her greatest battles as an educator were with his disciples.

John Dewey, whose ideas were to education what AIDS was to . . . education.

Hamilton retired from the Bryn Mawr School in 1922 at the age of 55. Her peers probably expected that she would move to the country, travel, putter around her garden for a decade or two, and go the way of all flesh. Instead, the timeless and rootless Hamilton began an entirely new life that would last nearly as long as her old one. With her new companion Doris Reid, daughter of a family friend, a former student and 28 years her junior (even then viewed as a bit controversial), she left Baltimore behind, moved to New York, and became a fixture in the world of live theater, not as an actress, but as an expert on Ancient Greek drama, then enjoying a bit of a post-WWI revival. She made friends in the publishing world just as easily, and began writing articles for theater papers. She translated Aeschylus’ Agamemnon , Sophocles’ Prometheus Bound, and Euripides’ The Trojan Women, the second of which appeared in Theatre Arts Monthly, and which were all eventually published together as a book, Three Greek Plays. Some of her new friends put her up to writing an original book, which became 1930’s The Greek Way.

The book was a hit (and still in print, like all her books) and introduced Hamilton to an even wider circle of friends and associates. This would continue as she published further books- The Roman Way (1932), The Prophets of Israel (1936), and the aforementioned Three Greek Plays (1937). Hamilton’s late-life celebrity was astonishing- a quiet schoolmistress in retirement became the center of an interlocking network of international salons filled with a diverse array of the world’s writers, artists, politicians, generals, and sundry others. It wasn’t as if she’d been unknown and isolated in her prior career; she was personally acquainted with John Dewey, Woodrow Wilson, and Gertrude Stein, among others, and had been all over Europe as well as China and Japan before she retired. But now her life was a cynosure of social activity. She knew Basil Gildersleeve and Gonzalez Lodge, entertained Bertrand Russell, and corresponded with Werner Jaeger. Later in life, when she moved to Washington DC, Hamilton socialized with Alice Roosevelt Longworth, Gen. Albert Wedemeyer, Henry Cabot Lodge, John L. Lewis, Robert Frost, and worked alongside Ezra Pound during his stint in a mental hospital after WWII.

The warm, grandfatherly Pound, seen here waving hello.

The WWII era had a profound impact on Hamilton. The experience of WWI, and the subsequent Spanish Flu that had forced her to close her school, had left her, and a generation, with a crisis of faith; WWII, a second disaster in as many decades, compounded the feeling exponentially. Hamilton’s basic faith in the progressive orientation of mankind was sorely tested by the fact that the most civilized people, to her mind, seemed most inclined to exterminate each other. Teacher that she was, she realized what was needed- a return to the roots, to the fundamentals of Western Civilization. And so, in 1942, at the height of the war, she published her Mythology.

Mythology is simply a masterpiece, a guided tour through the stories of Ancient Greece and Rome by an author who had spent a lifetime among them. The stories are arranged topically with explanatory text by Hamilton noting the ancient authors who wrote the stories and detailed descriptions of the cultural significance of the various mythological figures. The book is relatively short and extremely readable, the very opposite of Frazer and a worthy successor to Bullfinch. A section at the end, briefly covering Norse myth, hints at the wider possibilities for Hamilton as a comparativist, but apart from that and her forays into Ancient Judaism and early Christianity, she left that aspect of scholarship unexplored.

Indeed, what is unsaid in Mythology says as much about Hamilton’s approach to scholarship as what is. The book is notable for what it isn’t. There is no attempt in Mythology to theorize about the nature of myth in any contemporary academic sense. None of the greats of 19th century comparative myth show up; there is no influence from Müller, Durkheim, Levi, Propp, Freud, Nietzsche, or anyone else. Nor does Hamilton reference her own contemporaries. She had read Jane Harrison’s Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Myth and corresponded with Eliade, but nothing of either of their body of work makes an appearance. If she was aware of Dumezil or the great project of contextualizing Greek myth into the wider family of Indo-European religion it is not apparent. Her views on myth were formed solely from her own interpretations of Classical texts read in the original languages. Edith Hamilton’s Mythology was purely Edith Hamilton’s.

Nietzsche’s stunned look upon hearing that someone on the internet wasn’t talking about him.

In terms of her relationship with the wider world of scholarship Hamilton is a bit of an enigma. She knew the actresses of off-Broadway New York but never made the acquaintance of Alice Kober just down the road, then busy deciphering Linear B and proving that the Greek presence in their homeland was far older than imagined. Her many trips to England, including to Oxford and Cambridge, never brought her into the orbit of the Inklings, themselves busy popularizers of myth and Christianity. She seems to have been unaware of the work of Marija Gimbutas, which presumably would have been of interest to her even late in life, nor Jung or Campbell. In truth, Hamilton seemed to dislike and feel alienated from academia. She had been forced to give up her early dream of getting a PhD both by financial considerations and the unwelcoming atmosphere of university life. Knowing that she was more than capable of doing the work must have only made it worse. While there is no hint of resentment in Hamilton’s writings, she never made any special effort to associate with professors, seek their approval, or become one of them, though she easily could have in the wake of her late-life success. She was a thoroughly independent woman in every sense, untethered to convention, to time or place, or as numerous witnesses could attest, the physical limitations of aging.

In many ways, the figure she most resembles is not any academic but writer Dominick Dunne. Mark Steyn famously said of him, “Dunne’s whole life was like that: everybody who was anybody wandered in and out of it like characters in a brilliantly plotted Big Novel.” So too it was with Hamilton. Like Dunne, she was a popular writer; like Dunne, she was shaped by an unconventional but somehow unremarkable sexuality, and like Dunne, she was a wonderful conversationalist able to move among a staggeringly diverse array of important people in all areas of life. Dunne lived long enough to attend Robert F. Kennedy’s wedding and see his nephew jailed for rape and murder decades later. Hamilton was born two years after the Civil War and lived to comment on Jack Kennedy’s Space Race (not a fan). They were observers, commentators, and only occasionally and by necessity participants in great controversies; they were each in the world, but not quite of it, oddballs and eccentrics who somehow remained popular with a growing cast of characters. They would have made a great couple, in some sense, I think.

Read A Season in Purgatory, seriously.

Hamilton was only midway through her writing career with Mythology. Still to come were The Great Age of Greek Literature (1942),Witness to the Truth: Christ and His Interpreters (1948), and Spokesmen for God (1949). As the last two books indicated, Hamilton was increasingly drawn back into the religion of her youth in later years, but typically, she drew creative- if somewhat strained- parallels with Greek culture. She noted that the poets indulged in a kind of monotheism; she read Plutarch and Plato deeply. The real problems of Western Civilization were to her ultimately spiritual and her program was for renewal remained the same, a return to the values of Golden Age Athens and a creedless Christianity compatible with the same. Her final book, published when she was nearly 90, was The Echo of Greece. It was a true magnum opus, a final plea to a world lost to materialism, modernism, and cynicism to return to itself.

She lived long enough to make a trip to Athens to be made a citizen at the age of 90, which was the crowning glory of her life, at last having been invited home. Still, nothing slowed her down. She was working on yet another book, published posthumously as The Collected Dialogues of Plato, when she passed away in 1963 at the age of 95. She missed the real 1960s by but a hair, and had she not been gathered to her ancestors she would only have had to have lived five more years to hear Robert Kennedy address an audience with the words of her translation of Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, perhaps the last time an American statesman both knew and could count on his audience to know the reference. It is a testament to how much we have lost.

So what lessons can we learn from the life and work of Edith Hamilton? First, one has exactly as much life as one is meant to have. One should never have any idea that things are just beginning or that they are coming to a close. Hamilton might have died any number of times (she had numerous surgeries for cancer even as a younger woman) and yet she did not. She lived more than a full life, more than two full lives really. It’s never over until you’ve seen your last sunset, and only those you leave behind will know when that is. Never think your life is over and never assume you have another day. Do the work you are meant to do.

Second, Hamilton chose the life she wanted and accepted the sacrifices that came with it. She wanted a career and forsook a family in the conventional sense. This is a sacrifice made by priests and soldiers alike, the forces that preserve civilization, and so too must it sometime be for scholars and artists. This was not a decision entered into lightly or selfishly; Hamilton didn’t forsake marriage and her own children (she semi-adopted a nephew of Reid’s) so she could watch Netflix and chill. The duties are the same whether one has a family or not, the debt we owe those who came before us to preserve and pass on what we are given.

Third, the life of the mind is for anyone. Hamilton’s circles contained few professional academics. The people drawn to her were politicians, poets, generals, businessmen, artists, actors, and housewives. They shared a love of culture unconnected with career and material gain. While I am a teacher by profession, I work to move past the limits of my own field into every area I can, and I hope to interact with the widest range of people possible. My life’s project is less political and educational than it is spiritual and artistic. My grandmother, a former waitress at a Florida country club, gave me a great gift that day at Waldenbooks, and in everything I’ve done since then I’ve endeavored to pass that gift on. If you are a waitress; if you are struggling in miserable job you hate; if people don’t appreciate you, know that you are not those things. You are made in the image of God and bear the gift of reason, and have within you the ability to surpass your circumstances.

I encourage you all to go out today and read Edith Hamilton’s Mythology. But even more than that, give away a copy as a gift. You never know whose life you will touch with it, or any other like gift you might offer. My teachers will never really know what they did for me, nor my family, nor, especially, will Edith Hamilton. I can only hope to do her memory justice by giving her her due here, and to exhort you as she would have to fully embrace your potential.

What a loving tribute to a true mentor. Although you never met , it's clear that she has had such a deep and indelible influence on you.

I don't know how I could have read your post WITHOUT getting ahold of Mythology.

My young introduction to myths was D'Aulaires' , with Greek and Norse. Much more of a children's book with all those wonderful pictures.

Somewhere Edith Hamilton is smiling.

Wow! I remember enjoying that book when I was assigned to read it in middle school, despite the fact that it mostly went over my head at the time. I see I need to revisit it, and you have inspired me to do that. What a beautiful tribute to a most remarkable lady!