Growing up as a small child in the 1980s, I lived through the golden age of horror. Slasher villains like Freddy, Jason, and Leatherface joined Michael Myers as household names. For sci-fi horror one had Alien and Predator; for body horror there was Cronenberg’s The Fly and, one might argue, The Thing and Robocop. I have little doubt my readers are unfamiliar with these and could list far more. Many of you probably retain memories of being terrified by these films. I do not.

The Fat Boys don’t seem particularly impressed themselves.

That’s not to say that as I passed from childhood into my teen years and beyond that I never found a film to be scary. It’s that I wasn’t really scared of the ones that were meant to be scary, or rather, the ones that depended merely on the specter of death or mutilation or whatever. The monsters in your typical horror movie had one thing in common that to me, even from a young age, made them sub-par as credible threats: they were comprehensible. Freddy had a backstory and Freddy had rules; he could be defeated by weaponizing discoverable weaknesses. They were all, despite however monstrous they appeared, ultimately anchored in some reality that operated according to human logic. The things that scared me were the things that were truly alien.

By alien I don’t (necessarily) mean something from another planet. I mean rather something that is simply beyond human understanding. Something with drives and motives that remain as mysterious at the end of a film as they do at the beginning. This is hard for a filmmaker to do well, as an audience will naturally gravitate to something it can understand and one can leave viewers with a sense of anger rather than unease if it is done poorly.

Most reviewers would say that Communion (1989) was just such a poor film. It came and went in the theaters and I only know about it from my parents having rented it on VHS. I was ten years old when we watched it, or rather, watched as much of it as I could; I barely remember the film from that first viewing. What I recall instead were the nightmares. I could not sleep for what must have been a week after watching that movie. To this day, one particular night haunts me. I awoke around midnight or so after some bad dream and peering out from my bed, half-awake, I saw one of them. It was laying on the floor under a nightlight, propped up in a way that was inhuman. I shut my eyes as tight as I could and looked again. It was still there. I swear I saw it move. Over and over, clenched up in terror, I forced open my eyes and saw it. I remember screaming for help, and my dad rushing into the room. When he turned on the lights the being was still there, now revealed to be a pile of clothes and now-vanished shadows. When you read the negative reviews for Communion, ask yourself if Maniac Cop ever scared anyone like that.

You forgot about Maniac Cop, didn’t you? It had Bruce Campbell, Richard Roundtree, and Robert Z’Dar. Go watch it.

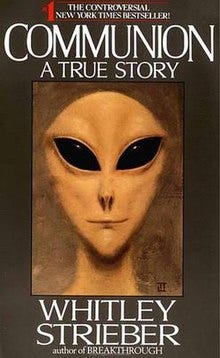

The movie Communion was based on the book Communion, written by Whitley Strieber two years earlier. Strieber is his own story, one of those under-the-radar artists that contributes in a monumental but largely now-forgotten way to popular culture. A longtime writer of horror and science fiction, in the mid-1980s Strieber began to document what he insisted were nonfictional accounts of his contacts with non-human entities. Communion represents his first major literary attempt at this. This is the cover of the book.

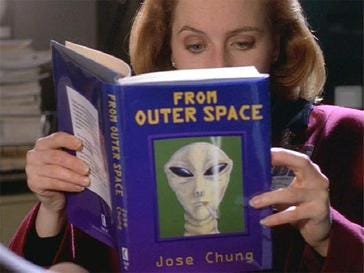

You will see research describing Grey aliens as being linked to the Betty and Barney Hill Abductions, the Rowell Crash, and even earlier. This is a huge retcon. Strieber invented (or introduced) the Grey, and from there it was backfilled into UFO lore as the standard alien, so prevalent did this image become. It is very much the icon at the center of UFO culture, further popularized by the X-Files, which debuted four years after the film.

The picture is of a being that haunts an abyssal canyon in the black ocean depths of the Uncanny Valley. It is human enough to be familiar but twisted just enough to be both compelling and repulsive all at once, a master study of Freudian ambiguity. The smooth skin and neotenous features evoke new life, but those same large baby eyes are black and hollow and angular, and along with the slit nose give the impression of a warped Totenkopf. It is neither masculine nor feminine. Its face is both expressionless and menacing, right down to the Mona Lisa smile. Its humanoid presentation blends features of the avian and insectoid and is equal parts organic and robotic. Grey is a bit of a misnomer, as the being really presents in a sort of institutional beige, evoking a kind of timeless, unanchored deracination, a creature of the hive, undifferentiated and fungible, a corporate drone of the Backrooms. It pushes buttons in the brain one would otherwise be unaware of were one not to have encountered the image.

I still remember seeing the paperback version of this book on sale at the grocery store when I was a kid, and even then it unsettled me. Communion is now fairly obscure, but it was a bestseller in its day, and the success of the book is what paved the way for the film. There were other books coming onto the scene dealing with the abduction phenomenon, most notably Budd Hopkins’ Intruders (made into a TV movie in 1992). But Strieber and his book differed from the others in the genre in important ways, which influenced the film for good and ill.

Strieber was already a science fiction and horror writer before he began reporting his experiences, which naturally led skeptics to conclude that his “non”fiction was just a clever way of marketing his stories. Alien abduction had been a hot topic since the late 1970s and selling books was, after all, his existing job. For his part, Strieber (who is still alive and writing) maintains that it’s quite the other way around, that he has since come to remember having been a part of encounters with otherworldly beings since childhood, and that those encounters formed the basis for his career in literature. He has written a number of books since then elaborating on his experience before and since the events described in Communion. Also, and this is a point the movie obscures, Strieber is adamantly against calling the beings with whom he interacted “aliens” in the sense of a non-human species from another planet. Despite his Greys having since accumulated a great body of lore surrounding their origins and purpose in the UFO community, he himself remains fully agnostic as to what they are, and describes the phenomenon in terms that are as much psychic and spiritual as physical.

The story of Communion, the book and the film, center on experiences Strieber claims he had in 1985 while at his cabin in upstate New York. He awoke under paralysis and was taken from his room by beings like the one depicted on the cover (Strieber worked personally with the artist), who then performed science-like experiments on him, all of which seemed to involve degrees of sexual violation. He was then returned to his home with no memory of the encounters, which only emerged under hypnosis later on. The last parts of the book involve his trying to understand what happened to him, both in terms of science and myth and religion.

You can watch the whole film above. The scene starting at 12:00 is literally the scariest thing I’ve ever seen on film. Watching it again, at the age of nearly 45, I still get goosebumps.

The film had its work cut out for it with such caveats in mind. A straight alien abduction scenario would certainly work, but it would not really be true to Strieber’s main theme of what can only be described as epistemological terror, a great unknowing at the heart of the mystery of what happened to him, and in a meta sense, the unknowability on the part of the readers/viewers, who have to decide not only what happened, but if anything happened at all. The introduction of the possibility of manufactured or deleted memory, as explored in Dark City, means that everyone is a potential unreliable narrator, and in fact has a sort of contingent and subjective self-awareness. In that way, the questions about the fiction vs. nonfiction character of Strieber’s work lend themselves to a still bigger controversy; it can be just as plausible that his non-fiction is really fiction as it is that his fiction is really nonfiction, in the sense that if these beings have been influencing him his whole life, then perhaps his creations are really aspects of experiences.

This is, by the way, something one runs into all the time in UFO lore, a blurring of exactly those sorts of boundaries. John Keel, author of The Mothman Visitations (later The Mothman Prophecies, also made into a film) always came across as equal parts credulous believer, hard-nosed critic, fabulist, and victim of conscious hoaxes on the part of his fellow paranormal researchers. Budd Hopkins, pioneer of regressive hypnosis, was also an visual artist, and it is unclear to what degree the recovered memories of his subjects were their own and how much they represented his creative touch. It is, to say the least, unsettling.

The film stars Christopher Walken as Strieber, a casting choice that all involve seem to have regarded as a mistake. Strieber was meant to have been seen as a kind of everyman and Walken is, well, Walken- the best character actor one can have if the character is meant to be Christopher Walken. For my part, I disagree with that negative assessment. I think that Walken, who is scary even when not intending to be, lends something important to the role, in that watching this intimidating person getting abducted by gracile creatures just serves to illustrate how scary they are. And Walken’s acting is really of a piece with the overall tone of the film. Australian Director Phillipe Mora seems to have decided on a kind of surrealist approach to the story, as if David Lynch had directed an episode of the X-Files [WHY HAS THAT NOT HAPPENED?!] and honestly I think Walken fits well into that approach.

Those choices play out well in some ways and not in others. The best, and scariest, parts of the film are the dreams and hypnotic regressions, where innocent aspects of daily life, like owls and toys, are revealed as symbolic masks for the presence of the entities that abduct him. This scene is typical.

As with the book, the film never explicitly reveals what the entities abducting Strieber actually are, and little about their purpose in doing so is ever made clear. The film is not Strieber fighting the entities nor even figuring out what they want, but rather coming to terms with the fact that they have played a presence in his life from his early years, and that it seems they will also be visiting his son. They come when they wish, abduct him and violate him, his body paralyzed, his friends and family unable to help him. It is a truly frightening spectacle, with which he is left to cope by taking what ownership of the situation as he can and letting go what he cannot fathom. In this, he retains his sanity (ostensibly) and the audience is left with a vaguely hopeful message.

All of this works well enough, but the film is hampered by a few factors. One, audiences expected aliens, and the subtleties and ambiguities of Strieber’s story were a bit much for them. In much the same way, viewers and the studio were conditioned to expect Braveheart or Gladiator or Troy when Alexander debuted, and the same result occurred. This might have been mitigated by going still more surreal with it, but as an independent film with a not-especially huge budget, this was likely the limit of what they could do at the time. You’ll note that the small blue “assistant” aliens look an awful lot like the Lurkers from Phantasm; some have called them Jawas. The special effects, while good enough for the time, are a bit dated now. But more than anything, the lack of a clear resolution, with Strieber rescuing his son and defeating the aliens, seems to have left viewers unsettled. These “aliens” weren’t tricked into airlocks or crushed by logs. It wasn’t even altogether clear that they didn’t wholly exist in Strieber’s head.

And that, in the end, is the scary part for me. What makes this film truly terrifying is the way it bleeds into real life, a sci-fi author writing a book that becomes a movie about a sci-fi author writing a book in which he is the main character describing experiences that could happen to anyone, or at least, could be believed to have happened. You might think you have been abducted, but it is an artifact of delusion, or you might experience vague hints of cosmic horrors every time you see an owl. The reality you think you know might be a façade constructed by subtle and malign beings for their own very alien ends. I think as a whole Communion captured this sense of existential dread very well, as did the X-Files episode that most closely referenced and thematically aligned with it it (the best episode of the series), “Jose Chung’s From Outer Space.”

Meta!

One may ask, in closing, what I think of Strieber’s story. My honest answer is that I don’t know. I believe in a God that gave humans the gift of reason and the power to know things about our universe, but also that, for our own good, some areas are simply closed to our knowledge. As I noted in my last essay, I consider the phenomenon as a whole to be most likely demonic in its essence, and thus avoided. Artistic representations of “alien” abductions, when done well as Communion was, point to this truth, and are thus edifying, but were I in the position Strieber was in, I would make the sign of the cross, turn my gaze within, and say a prayer. I can say that attempting to read the later books he wrote about his experiences long after I became an adult left me feeling deeply disturbed on a visceral level, and I have never fully gotten through one. I can thus personally attest to how affecting the phenomenon is at a distance; I can only imagine what the experience would be like if it were in my real life. I wonder even still about that pile of clothes . . .

"Walken is, well, Walken- the best character actor one can have if the character is meant to be Christopher Walken." hahaha this is so true!

But this whole article is fantastic; great analysis of a severely underrated film. Rewatching some of Communion gave me the heebie-jeebies again too!

I used to be terrified of Greys when I was kid. Anything even remotely resembling a stereotypical alien would leave me in shambles for weeks. I can only imagine the reaction I would've had if I stumbled across this film. The 80s just seemed to have had a knack for making bizarre movies.