[Do also check out

’s work on Eliade; he goes far more into the concept of the sacred and the profane than I do]Mircea Eliade was perhaps the most important historian and theorist of religion of the 20th century, a mythographer of the first order whose work has much to say about our current condition in the West. Controversial especially since his death for some of his associations in his younger years, Eliade nonetheless remains influential in his field, with some of the concepts he developed, hierophany, the dichotomy of the sacred and the profane, and the eternal return still central in religious studies today. But though an academic by profession, Eliade was far more than a cloistered scholar. His work was far less about observation than experience; more than understanding how the mental and spiritual life of archaic humanity had developed into modern ideas, he sought out to create a kind of praxis of authenticity, searching by way of myth for Traditional spiritual truth.

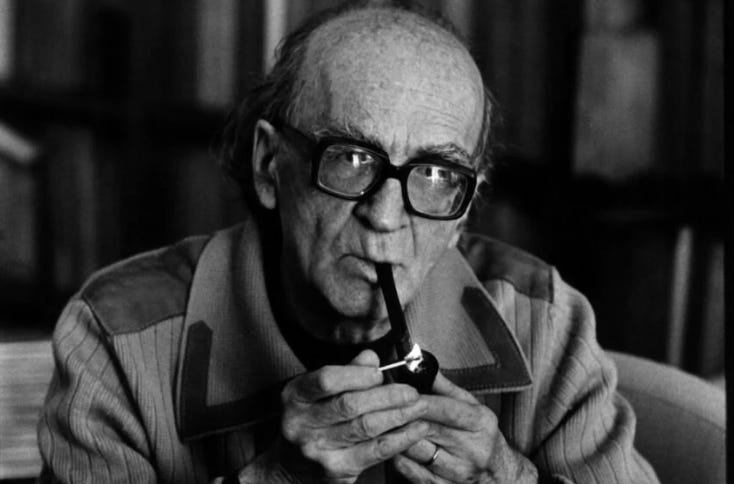

Sometimes a pipe is just a pipe, and sometimes it’s the mythic instantiation of divine illumination.

He was born in 1907 in Bucharest in what was then the Kingdom of Romania. His family was middle class and he recalled a happy childhood, marked by a particular experience that he regarded as an epiphany- walking into a drawing room bathed in an "eerie iridescent light" which temporarily removed him from the realm of consciously experienced time and place and into a state of “plenitude.” The quest to understand and experience such things would become the quest of his life. It would take him to some interesting places.

The young Eliade, as befitted someone who had experienced a personal revelation of the spiritual realm, was dissatisfied with the education on offer locally. He did so poorly in school that at one point he was failing Romanian. Most of his learning occurred from his own initiative, and from an early age he exhibited enormous literary potential- he was a published author at 14 and wrote an autobiography at 18. A polyglot with a great talent for languages, he would study over the course of his life numerous European tongues as well as Hebrew, Persian, Sanskrit, Pali, Bengali, and others. He spent years living abroad, in Italy, Egypt, India- his PhD dissertation from the University of Bucharest concerned yoga- and various European countries. In this, his life mirrors so many of the other great mythographers of his age, Dumezil, Gimbutas, Hamilton- they were people at home anywhere because, in their hearts, they were really living anytime; being essentially timeless creatures, they would have been just as comfortable or alienated at home or in some foreign land.

Sadly, Eliade is remembered in his hometown mainly as an Elvis impersonator.

His cosmopolitanism, however, seemingly contrasted sharply with many of his political and social beliefs, especially in his younger years. One might expect that a man who attended ashrams and who had had numerous affairs with numerous women would be some sort of proto-hippy free love universalist. Eliade was instead, like many young men of his inter-war generation living in Romania, drawn to extremes of nationalism and religious sectarianism. The erstwhile expatriate expert on Hinduism was at the same time a revanchist chauvinist, committed to a vision of Romania as one purified of foreign elements, theocratically united under the Romanian Orthodox Church. His exact level of association with the Legion of the Archangel Michael is disputed, though he was never personally involved with the militant wing, known as the Iron Guard. But he was loyal to the Legion and its leader, Cornelieu Codreanu, such that he served a stint in jail rather than repudiate them. He deplored violence against Jews and, unlike many other Traditionalists, would defend the spiritual value of Jewish monotheism and its linear conceptualization of time, especially as it pertained to Christianity, for the rest of his life. But he also never explicitly rejected the violently anti-semitic Guard. I say seemingly because the contrast fades upon deeper analysis. Authentic love of the general springs from relationships with the particular; one loves man because one has learned to love men. In his youth this love of the particular manifested as political radicalism. But he evolved. Like Georges Dumezil and Edith Hamilton (both of whom he came to know) his political, religious, and social ideas were sui generis and a reflection of much time spent in worlds other than the present- he was in many ways both pre- and post-modern. After WWII, he largely withdrew from political activities, wisely focusing on scholarship.

The Iron Guard was ahead of its time in many ways. Most organizations today are also best represented by boxes to be checked.

That would come with his entry into the United States, as the communist takeover of Romania meant that he was a marked man there. Through connections, the now penurious Eliade first got a job teaching French at a small private school in Arizona in 1947. I like to think about that- this intellectual titan, already an academic celebrity, a man who socialized with Carl Schmitt and Jose Ortega y Gasset, going over verb conjugations by rote with a bunch of bored teenagers- “Je…m’ap…pelle…Mon…sieur…Eliade…d’accord?” However, this eventually fell through and he bounced around Western Europe for a while, working with Dumezil, Carl Jung, Ernst Junger, Gershom Scholem, Georges Bataille, Henry Radin, and many others- a sort of right-wing pilgrim sitting at the feet of the sages of Europe’s period of ashen penitence. But in 1956 he would return at the invitation of his friend Joachim Wach at the University of Chicago. Wach was one of the foremost scholars of religion in the US and he in turn regarded Eliade highly. When Wach suddenly died before Eliade could give the lectures for which he’d been summoned, the university decided simply to give Eliade Wach’s now vacant job. He would hold that position for the rest of his life.

Eliade reshaped the whole paradigm of the academic study of religion and did so in a way wholly in keeping with right wing- indeed Traditionalist- thinking. It is possible that no other area of academia is so subversively permeated with rightist ideas, even when given the gloss of '“queering” and such. One has to dig a bit, but turn over the shovel enough times and one will see Eliade emerging from his unquiet grave. To understand this, it is important to remember that the 19th century had been the great age of the proto-deboonker. Beginning with the great skeptical revolution launched during the Enlightenment, and given formal academic grounding by men like Julius Wellhausen, James Frazer, and Emile Durkheim, the approach to the study of religion had been largely functionalist and reductive. Freud and Marx each believed that religion was simply a mask for some more empirical phenomenon, and their ideas filtered down broadly to the midwits of their day. Religion is really just a manifestation of some animal instinct, or some material interest, or some primitive and long-redundant proto-science, or else the sacralization social norms, hierarchies, patriarchy, economic exploitation, or psychological disturbance. What it certainly is not is any kind of real approximation of the the supernatural, which is outside the realm of empirical study, not science, and not real.

Christianity can’t be destroyed, doomer.

Eliade’s bold claim was that archaic, pre-philosophical man had a profoundly different understanding of himself and his place in the universe, with an intuitive and permeating connection with a very real spiritual world. It was his belief that the echoes of this worldview continued on into man’s civilized, literate period, where older forms persisted, often enigmatically. In books like The Sacred and the Profane and The Myth of the Eternal Return, Elide described primordial men as experiencing things as real only inasmuch as they corresponded to timeless and placeless models from a “time of myth,” a sacred age when things first came into being. Men were men insofar as they were like the men of that age; all significant actions, events, objects, places, and even names partook of the eternal to the degree they were real. Such things as corresponded to mythical models formed the ‘sacred.’ ‘Profane’ life was that which was apart from this, those things without significance, and the object of a society possessed of this mindset would necessarily be to created personal and collective passages into that age of myth by performing rituals, establishing sacred spaces like temples, and creating art, all of which related to eternal models. Life was cyclical; men experienced the seasons as a recapitulation of the age of myth and its passing into corruption and profanity, only to be renewed, again and again. This is the eternal return, not to be confused with later Stoic and such ideas.

In fact, it was the emergence of philosophy that began a process of alienation from the sacred; Eliade believed this change occurred during the Axial Age. The educated classes of society, applying reason to ritual, stripped themselves of access to that more intimate, intuitive relationship with the sacred their forebears had enjoyed. They experienced the eternal return as a painful alienation from meaning, as their own actions could only be significant inasmuch as the corresponded to mythical models. This sense of a lack of freedom was painful, and the notion that cycles of death and rebirth are a kind of punishment became common in both Eastern and some aspects of Western thought. One sought Nirvana, or noesis; to gain some individual insight that would liberate you from this meaninglessness.

There was also the incipient awareness of linear time, the idea that events did not cycle, but began and ended, with all the impermanence that implied. That created what Eliade termed the “terror of history,” the notion that one lives in an unfolding series of meaningless events over which one has little control. Eliade credits the Jews for this leap in human awareness; uniquely, their religion envisions a God who creates ex nihilo and who promises that his created order will one day experience a culminating apocalypse and end. Modern man has embraced this linear view of time, but his horror is no less real. All of modern philosophy, for Eliade- including science- is centered on dealing with the spiritual crisis arising from this terror of history. His key insight was this inversion of values- scientists think they are on an empirical quest to understand religion, but really, they are on a religious quest to give spiritual significance to science, in the vain hope of deriving ought from is. We are not experiencing progress, but rather, retreat from higher truth. These profane philosophers have demonstrated empirically that man lives by bread alone, and they are starving.

In this sense, Eliade’s achievement was to change the whole ethos of religious studies from smug whiggist progressivism to the valorization of RETVRN. Certainly, it generally manifests in practice as woke twaddle; neopronoun-infested drum circles banging away, trying to awaken Baal. But the core of a very useful idea is there, a mutation in the academic code. Like all such changes, it renders some creatures helpless before nature, but for others, it makes for the possibility of new forms of life. It’s the very opposite of the woke mind-virus, the inception like idea that grows- under the right conditions- into a full on epiphany: the world you see is not as real as the one you don’t, and reality is nested and contingent on higher things. There is great power in this.

Christianity is in a unique place in all of this, a religion that alone sacralizes time and historicizes the mythic past. The elements of the eternal return instantiate themselves fully into recorded time, in particular places- at once transcendent and immanent. The cycle is broken with the atoning Death of Christ, an event wholly unique and bound up with human witness, but its effects extend eternally through the Son’s relationship with the Father. The Church at once participates in an eternal return (every Divine Liturgy takes place at once in heaven and earth, church divine and militant), while at the same time retaining its historical character as an institution with a lived temporal life. The terror of history is broken, however, but the infusion of meaning into the changeable realm. This is what modern, profane man has abandoned. All of modern philosophy, science, and politics centers on finding a substitute that accords with the wisdom of the world. But the wisdom of the world is foolishness to God, the foolishness of primeval man finding comfort in his unbothered intuitive contemplations.

Eliade, like so many Traditionalists, never seems to have fully embraced this line of thought. Private about his beliefs in his later years, he, like Evola, was cremated after death, which would indicate estrangement from the Orthodox Church of his youth. Saul Bellow gave the eulogy. His younger Romanian contemporary, Cleopa Ilie, would by contrast fully accept the truth of that faith, and in his adopted home of the US Seraphim Rose would build on the traditionalist philosophy of his youth in his own journey as an Orthodox monk.

This book is essential not only for understanding 20th century Christianity, but also Traditionalist thought from an Orthodox perspective.

Eliade laid the groundwork for much of contemporary reactionary religious thought, but was also a celebrated mainstream scholar of religion and myth whose body of work functions as a neglected open door for frens to enter the otherwise unassailable reaches of the Ivory Tower. A small-scale religion program, operating at the levels I noted in my series on teaching, could serve as a unifying structure from which more particular areas of study could spring. A body of clever young men and women, given a thorough ground not in myth and the transcendent, would thereby acquire a worldview both differentiated and elevated- whatever their life path they would be mindful of the higher things, illuminated. And truly, for Mircea Eliade, who sought his whole life a return to that epiphany of his youth, what better legacy could there be?

“All of modern philosophy, for Eliade- including science- is centered on dealing with the spiritual crisis arising from this terror of history. His key insight was this inversion of values- scientists think they are on an empirical quest to understand religion, but really, they are on a religious quest to give spiritual significance to science, in the vain hope of deriving ought from is. We are not experiencing progress, but rather, retreat from higher truth. These profane philosophers have demonstrated empirically that man lives by bread alone, and they are starving.“

this is a brilliant insight

I am reminded of Whitehead’s quip:

“Scientists, animated by the purpose of proving they are purposeless, constitute an interesting subject for study.”

“Without conscious rituals of loss and renewal, individuals and societies lose the capacity to experience the sorrows and joy that are essential for feeling fully human. Without them life flattens out, and meaning drains from both living and dying. Soon there is a death of meaning and an increase in meaningless deaths.”

Nailed it.