The Roman Empire was great, then it declined, and then it fell. This is something everyone just kind of knows. It started with a guy named Julius Caesar, got really big, then something happened and then it collapsed- Dark Ages, something something, Medieval times. What that initial something was is a matter of some debate- barbarian invasions, race-mixing, too much lead in the pipes, or perhaps, as Gibbon and his ideological successors would have it, Christianity?

There are really two big stories about the Roman Empire. The first is the one everyone knows, or thinks he knows, the one with Augustus and legions and aqueducts and a few mad tyrants like Caligula and Nero. But there is another story that isn’t so fixed a part of popular consciousness. And for all we like to imagine we are the cultural heirs to the Rome of the first story, the Rome of the second is actually far more formative. This is the story of Christian Rome, of the empire that came into being as the first story empire exhausted itself, the Rome of Late Antiquity. Pace Gibbon, it’s the story not of decline and fall but of imagination and resurrection, of a polity and a people finding a new understanding of themselves in a time of great conflict.

The story begins with a crisis, more specifically the Crisis of the Third Century. The Severan Dynasty collapsed into civil war, with rival claimants to imperial rule trampling all over the empire with their personal armies, each of which had to be funded by ever increasing extractions from an overexploited population. When taxation failed to meet expenses, the various emperors and pretenders turned to inflation, debasing the currency so thoroughly that trade ground to a halt. There were at least twenty-five emperors in the fifty years after the death of Severus Alexander in 235, the majority of whom overlapped each other as rivals and usurpers, meaning that even the well-intentioned weren’t around long enough to make any worthwhile reforms felt, and all that could be put into practice were short term solutions that ended up causing more serious problems down the line. Shortages of manpower, for example, led to the recruitment of barbarians, who also reacted to the chaos by launching raids and full-scale invasions. Thus, when the various emperors weren’t fighting each other, they were defending the porous borders, which meant more expense, more taxes, more debasement, and more venal mercenaries in the ranks.

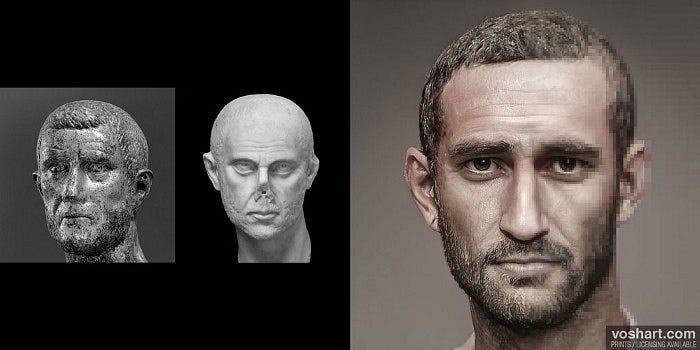

War is like a forest fire, destructive, but clearing the way for new growth, of men and ideas. The men who rose to the top during the Crisis of the Third Century were far in every way from Rome’s traditional senatorial elite- self-made leaders forged in battle, from provincial or even barbarian families, who owed their positions to their skill as commanders and their instincts for politics. One of these men was Diocles, probably a freedman’s son from Dalmatia born around 243, who rose from the common soldiery to become an officer under the Emperor Aurelian, eventually commanding the cavalry bodyguard of the Emperor Carus. Carus died under odd circumstances in 284- reportedly struck by lightning- leaving two imperial sons, Carinus in the west and Numerius in the east, the latter of whom Diocles was attached to at the time. Numerius then also died oddly- he was travelling in a closed palanquin due to some eye inflammation, then somehow passed away while no one was paying attention, so much so that only the smell of death alerted his bearers. One of his subordinates, Aper, made a bid to take over, but the other officers decided Diocles would be a more suitable candidate for power. Diocles accused Aper of assassinating Numerius, and illustrated his point by personally stabbing Aper to death in front of the whole army. He naturally came into conflict with Carinus as well, but as the latter had an unfortunate tendency to bed the wives of not only senators but his staff officers it was not hard for Diocles to suborn the necessary allegiances, and Carinus was killed by his own men. In only around a year’s time, Diocles had fairly handily dispatched his rivals and made himself the sole emperor. Befitting his exalted status, he gave himself a fancy new name, Gaius Valerius Diocletianus- better known to history as Diocletian.

Diocletian’s entire life had been defined by the Crisis of the Third Century and he was determined to end it. He instituted wage and price controls to try to stem inflation, which did not work well, but other reforms proved more enduring. He divided the empire into new administrative districts, reformed and systematized state finances, and rebuilt the army. But his most important changes were paradoxically the most short-lived.

Diocletian decided early in his rule that he needed able lieutenants in situ throughout the empire in order to enforce his reforms and bring stability. One would be a partner emperor, inferior only to Diocletian himself, but also with the title of Augustus. Each Augustus would have a subordinate with the title of Caesar, with the understanding that the Caesars would succeed the Augusti and appoint Caesars in turn. The overall idea was to allow Diocletian to rule in many places at once while also clearly establishing stability for the regime. Diocletian would post up in Nicomedia in northwestern Asia Minor, while his fellow Augustus, Maximian, would serve in the West based in Augusta Trevorum, modern Trier. Maximian was a fellow officer and a friend who had similarly gotten his start under Aurelian, and his Caesar was to be another from that circle, Flavius Constantius. The other Caesar, under Diocletian, would be Galerius Valerius Maximinus- Galerius, another Aurelian veteran, more on him shortly. This system of two emperors and two assistant emperors, four in all, would be known as the Tetrarchy.

Serving under Aurelian had been formative in different ways for Maximian, Diocletian, Galerius, and Constantius. For the first two, it was a training ground for what a strong-willed, imaginative emperor with an army behind him might accomplish. Aurelian had, between 270 and 275, launched a series of brilliant campaigns that destroyed a host of rivals and invaders, reuniting the empire under his personal rule, which the Tetrarchs, as younger men, had participated in and in which they’d learned the art of command. He was a reformer who had sought to end the Crisis through the same sorts of reforms Diocletian would later embark upon. But Aurelian’s promising start had been cut short in another strange death; a strict moralist, he had punished a minor civil servant over some discrepancy, who then forged a letter from the emperor ordering the deaths of a group of more prominent men, and having shown it to them as though he’d intercepted it, the men conspired and murdered Aurelian on that false pretext, thinking they were defending themselves. Gammacide.

But for Constantius, there was perhaps another legacy. Aurelian was the special devotee of the god Sol Invictus. The exact nature of this deity is vague in the sources. Rome had a traditional sun god, Sol Indiges, and Elagabalus had brought the worship of his eastern version to Rome, the cult of whom long outlasted the cross-dressing teenaged emperor who patronized him. It could be that Sol Invictus was meant to be the same god as one or both of those, or that Aurelian meant him to be all that and more. Monotheism, in some sense or another, was very much a part of the thought-world of Late Antiquity. The Neoplatonists conceived of a One beyond all human comprehension who manifested into the world through successive descending emanations. There were also syncretistic tendencies, the idea that the same god could appear under different names to different people. Sol, the personified sun, had an analogue in the Greek Helios, both of whom in turn often shaded into Apollo, god of light, reason, and prophesy. Augustus had been a special devotee of the latter. There were in addition two strong influences from the east- the Zoroastrian/Persian, which inspired various dualist and quasi-monotheist sects featuring theology and rituals involving light, fire, and cosmic sacrifice, like the Mithraics and Manichaeans, and the Jews, whose idea of a universal single God distinct from the created universe yet immanent within it. The latter inspired a movement known as the theophoboi- ‘God-fearers’- gentiles who worshiped the Jewish God without formal conversion, less a single sect than a tendency, like gnosicism. Some combination of these influences may have been behind the cult of Theos Hupsistos, overlapping as it did with elements of all of the above and which in turn may have been connected in some way with Sol Invictus, whether philosophically or as part of a general trend.

Aurelian’s own brand of Sol worship owed much to his campaigns in the East, and the Historia Augusta connect this with Aurelian’s war in Palmyra.

After this, the whole issue of the war was decided near Emesa in a mighty battle fought against Zenobia and Zaba, her ally. When Aurelian's horsemen, now exhausted, were on the point of breaking their ranks and turning their backs, suddenly by the power of a supernatural agency, as was afterwards made known, a divine form spread encouragement throughout the foot-soldiers and rallied even the horsemen. Zenobia and Zaba were put to flight, and a victory was won in full. And so, having reduced the East to its former state, Aurelian entered Emesa as a conqueror, and at once made his way to the Temple of Elagabalus, to pay his vows as if by a duty common to all. But there he beheld that same divine form which he had seen supporting his cause in the battle. Wherefore he not only established temples there, dedicating gifts of great value, but he also built a temple to the Sun at Rome, which he consecrated with still greater pomp, as we shall relate in the proper place.

There was a battle, a vision, and a realization of a special destiny. Aurelian established a new priesthood and a new temple in which to worship. It would be too much to say that he intended to reform religion generally along these lines; there is simply nothing in the sources to suggest any kind of universal solar monotheist ‘church’ around which the empire could unite, though it could be argued that Aurelian had intended to privilege the cult of Sol Invictus in ways that suggest such reforms. It is easy enough though to imagine the appeal of such a cult, combining all the religious trends of the day into an official system under the patronage of the emperor. Aurelian was killed before anything like that could even be theorized, but something of this religious vision lived on in Constantius, and in Constantius’ son.

Apart from Constantius, the other members of the Tetrarchy were more determinedly traditional in their religious outlook. As parvenu warlords with little actual cultural connection to the empire they served save through a life in the barracks, it made sense for them to be inclined to consciously strive to be the realest of real Romans. Diocletian made it known that his regime was under the special guidance of Jupiter, while that of Maximian was patronized by Hercules. He saw the empire’s problems as fundamentally moral and religious, the people and his various tyrannical predecessors having forgotten their duties to the gods. Tradition meant everything, and tradition meant religious observance- revival.

Thinking along these lines necessarily meant an attack on Christianity. All of the emperors would have been familiar with the Church; even had they not traveled the empire on military campaigns Christians could be found everywhere in any case. Despite being perhaps 10% of the population of the empire they were ubiquitous in urban areas. A church sat within sight of Diocletian’s palace in Nicomedia, and members of his own household were probably of the faith. Technically illegal since the first century, Christianity had been subject to periodic persecution since then, alternating with periods of tolerance. Generally attacks on the Church were local, sometimes nothing more than lynchings, judicial or otherwise. More recently and ominously, the Emperor Decius had instigated an empire-wide strike against the religion in 249, followed by a similar campaign on the part of Valerius in 258. Both involved compelling all subjects in the empire to sacrifice to the gods on behalf of, and as a show of loyalty to, the emperor. The revival of tradition was bound up with support for the respective regimes, and a refusal to perform the rite of sacrifice was legally considered both sacrilegious and treasonous. In the Roman Empire there was nothing like the separation of state and religion as we are familiar with in the modern west; toleration existed only as far as beliefs did not challenge the government and as a concession to the material limits of state power. Here is Diocletian proscribing another troublesome novel sect around the same time:

As for these people (the Manichaeans), who set up new and unheard of sects contrary to the ancient rites, in order that in support of their perverse belief they might drive out those doctrines which had been granted to us in earlier times by divine influence, and concerning which Your Wisdom reported back to Our Serenity, we have heard that they, namely the Manichaeans, have arisen and advanced into this world very recently from among the Persians (a people antagonistic towards us ) just like new and unexpected prodigies, and where they are committing many crimes, for example troubling peaceful peoples and introducing the gravest damage to cities. We should be afraid that they might attempt, as is their wont, to corrupt men of more innocent natures, the modest and tranquil Roman race, and the whole of our empire with the deplorable customs and sinister laws of the Persians as if by the poisons from their own malevolence.

-Diocletian’s “Edict Against The Manichaeans”

Perhaps given that Decius had died shortly after issuing his anti-Christian edict and Valerian had shortly suffered the even more humiliating fate of being captured after a defeat in battle and turned into the personal slave of the Persian Shah, subsequent emperors chose not to tempt the fate and go after the Church for two generations. But with total power to reform things as Aurelian and his successors had never achieved, Diocletian saw his chance.

It wasn’t so much that he personally hated Christianity. With his contrived traditionalism, he simply viewed the faithful as deluded, obstinate, and unpatriotic, but no more so than the Manichaeans whom he also sought to render extinct, or the Druids wiped out by his predecessors. Still, things might not have gone as far as they did were it not for the influence of the Caesar Galerius. While all the late Crisis-era emperors were rough men to some degree, Galerius was a brute, coarse and violent without even a hint of an attempt at courtly polish. Like Stalin, he presented as thuggish, but also like Stalin this served to mask a feral intelligence and wholly ruthless political instincts, as well as a predilection for simple but strongly felt ideological fanaticism. And, just as Stalin-like, he truly despised Christianity.

Diocletian, taking some measure of his subordinate’s talents, stationed him on the eastern frontier as a kind of guard dog against Persian encroachment. Galerius, to continue the comparison with the Soviet leader, had the good fortune to be constantly underestimated, and was inclined to attack rather than defend, proving so successful that he soon drove the Persians out of territories they’d occupied for fifty years, looting and pillaging in the process. He quickly found himself in command of a huge war chest and an experienced and loyal army upon which to spend it. The relationship between himself and Diocletian took on a different cast.

It was Galerius who urged Diocletian, in 303, to wipe out the Church utterly. Not only the bishops, but the congregations, the buildings, the scriptures- all of it, root and branch, gone. It seems the main lesson he absorbed from Aurelian was the use of violence to compel conformity; his predecessor had been the first to style himself dominus et deus ( lord and god) and he had a persecution of Christians in the works himself, derailed only by his own murder. The fully realized purge of Galerius and Diocletian would be known as the Great Persecution. It would last ten years, and the fallout would color the history of the next century and all the centuries to come.

Shortly after instigating this, Galerius decided to make some political changes in addition to the religious ones. In 305, he informed a now sickly and increasingly aged Diocletian that it was time to retire. This would have made Maximian the senior Augustus, but Galerius decided Diocletian’s designated successor needed to spend time with his family as well, and the former was in no position to resist, having been markedly less successful on his campaigns against barbarians and rivals than Galerius. Constantius, however, was not so easily sidelined. Though only a Caesar, he had proven to be a far better general than his superior, campaigning in Gaul, Britain, and Germany and laying thorough waste to his enemies. Galerius was thus compelled to accept him as his new fellow Augustus. As for the new Caesars, it seemed obvious who they would be. There were only two legitimate sons within the Tetrarchy, Maximian’s- Maxentius, and Constantius’s -Constantine.

Constantine, destined to become one of the most important figures in world history, had been groomed for leadership from a young age. Growing up more or less as a hostage for his father’s good behavior at the eastern court of Diocletian, he had served with distinction under both him and Galerius, proving to be both personally brave and a talented commander. While some accounts portray him as a rough soldier with little education, it’s not an especially convincing take. Nicomedia was a huge and diverse city, a crossroads of culture, and Diocletian’s court featured such luminaries as Porphyry and Lactantius, the latter eventually exiled for his Christianity- more on him later. Throughout his life Constantine surrounded himself with intellectuals, both pagan and Christian, and would cultivate a cosmopolitan circle of advisors who greatly influenced his outlook. While he was not a philosopher in the strict sense, he was an introspective and reflective man, on some level uneasy with the religious life of his day, a bit like Muhammad, the Buddha, or Guru Nanak. Had things gone differently he might indeed have founded an influential world religion, as Aurelian might have. His fate was a bit different.

Constantine was there when Galerius announced the new Caesars, and … he was not one of them, nor was Maxentius. Galerius, it seems, preferred to stack the deck with his own cronies, naming Flavius Valerius Severus and Maximin Daza to those spots. Realizing that he was now dangerously surplus to requirements as a future leader in the east, Constantine surreptitiously fled the capital and made his way to his father’s court in Gaul. Maxentius, for his part, went straight to Rome, where his father was well-liked, and proclaimed himself emperor. Severus was sent to stop him but his army preferred Maxentius and Severus was murdered outside the city. Constantine served with his father for a short time on campaigns before the latter died, whereupon he too proclaimed himself Augustus in 306.

Galerius fumed at all of this, and after a few years was finally forced to bring Diocletian and Maximian out of retirement to lend their authority to a new settlement. Constantine would be a Caesar; a new creature of Galerius, Valerius Licinianus Licinius, would be the Augustus in the West, and Maxentius would still be considered a usurper. Everyone agreed to this and then promptly ignored it. Constantine continued to call himself Augustus. He had inherited a loyal, battle-tested army from his father and had spent his short reign leading it from victory to victory, and he also proved a talented administrator and patron. He saw no reason to back down from his claims and realized that no one could force him to do so, least of all Licinius, who had no power base in the west. Maxentius, a bit of a miserable non-entity, held Rome, but while he proved difficult to dislodge he could do nothing to further his interests. Daza resented being passed over for Licinius and started calling himself Augustus as well.

Galerius, for his part, was by now dying, and not dying well. He seems to have contracted some form of necrotizing fasciitis in his nether regions, which caused not only great pain but a gangrenous stench as well. Lactantius, who had been exiled from the court of Diocletian due to the latter’s Galerius-inspired anti-Christian policies, gave a long, schadenfreude-filled description of the emperor’s malady, which he naturally attributed to divine judgement. Interestingly, Galerius seems to have come to the same conclusion, formally ending the persecutions in 311, shortly before his agonizing death. This of course created just the kind of power vacuum the Tetrarchy was supposed to prevent, but was signally failing to do so.

If you’re interested in necrotizing fasciitis, click the link…

Another destabilizing element was the former Emperor Maximian. Diocletian was content to raise cabbages in his palace on the Dalmatian coast, but his colleague chafed at his forced retirement. He made his was alternately to Maxentius and Constantine, marrying his daughter Fausta to the latter along the way, but serially betrayed both his son and son-in-law repeatedly until he finally and conveniently hung himself in 310. The old promise of the Tetrarchy was gone.

This left everyone searching for new friends. Constantine allied with Licinius, marrying off his sister Constantia to him. Both relationships were very much marriages of convenience, as Constantine realized that Licinius was in a position either to ally with Maxentius or to take Rome militarily, and thereby gain much-needed legitimacy in the West. Constantine thus needed to deal with Maxentius before his rival did, and with Licinius busy with Daza in the east, Constantine marched south and crossed the alps in 312. Maxentius obliged Constantine by presumptively declaring war on him in any case, and despite his lack of military acumen, he would have a numerical advantage against Constantine, as the latter needed to leave the bulk of his army behind to defend his territories from barbarians and in the interest of moving quickly.

Constantine to this point had been tolerant of Christianity, even shown favor to the Church, but had not in any way committed to becoming a Christian. This was basically his father’s outlook as well. Alone among the Tetrarchs Constantius did not persecute the Church, save for some pro forma shutting down of assemblies. Interestingly, in 310, when Maximian died, Constantine’s coinage ceased to emphasize Mars and Hercules, the latter being the special patron of his father’s superior and his own father-in-law Maximian, and instead began to display Sol, and his coinage would continue in this way even after his public embrace of Christianity.

A probable line runs from Aurelian through Constantius to Constantine in an attachment to this deity and the vague monotheism represented by him. Constantius’ exact notions concerning Sol Invictus are debatable, but the sun, Apollo, and monotheistic imagery around himself and his son are a running theme in their propaganda. Constantine was even said by a panegyrist to have had a vison of the god Apollo; while this is not something Constantine claimed for himself, it does point to the sorts of ideas he was comfortable circulating about him. As we have seen, his closest circles included men like Sopater, a disciple of Iamblichus and a leading Neoplatonist philosopher as well as Christians like Lactantius. While it is impossible at this distance to make firm conclusions about the development of Constantine’s religious thought, it can be said conclusively that he had been influenced his whole life by monotheists and monotheistic beliefs of one form or another, both Christian and pagan, and his ideas were probably some blend of those influences, and would remain so arguably for the rest of his life.

Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea, writing his Life of Constantine decades later following personal interviews with the emperor, gives Constantine’s own considered reflection of those days. Something about the march on Rome seems to have inspired a sort of spiritual crisis in him, and he spent some period of time before the pivotal battle against Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge in prayer. By way of background, Eusebius (more on him later) describes Constantine’s father Constantius as a pious man who rejected idolatry and pagan sacrifice, yet never becomes a Christian, worshiping the “Supreme God,” but never Christ specifically.

Being convinced, however, that he [Constantine] needed some more powerful aid than his military forces could afford him, on account of the wicked and magical enchantments which were so diligently practiced by the tyrant, he sought Divine assistance, deeming the possession of arms and a numerous soldiery of secondary importance, but believing the co-operating power of Deity invincible and not to be shaken. He considered, therefore, on what God he might rely for protection and assistance. While engaged in this enquiry, the thought occurred to him, that, of the many emperors who had preceded him, those who had rested their hopes in a multitude of gods, and served them with sacrifices and offerings, had in the first place been deceived by flattering predictions, and oracles which promised them all prosperity, and at last had met with an unhappy end, while not one of their gods had stood by to warn them of the impending wrath of heaven; while one alone [Constantius] who had pursued an entirely opposite course, who had condemned their error, and honored the one Supreme God during his whole life, had found him to be the Saviour and Protector of his empire, and the Giver of every good thing. Reflecting on this, and well weighing the fact that they who had trusted in many gods had also fallen by manifold forms of death, without leaving behind them either family or offspring, stock, name, or memorial among men: while the God of his father had given to him, on the other hand, manifestations of his power and very many tokens: and considering farther that those who had already taken arms against the tyrant, and had marched to the battlefield under the protection of a multitude of gods, had met with a dishonorable end (for one of them had shamefully retreated from the contest without a blow, and the other, being slain in the midst of his own troops, became, as it were, the mere sport of death ); reviewing, I say, all these considerations, he judged it to be folly indeed to join in the idle worship of those who were no gods, and, after such convincing evidence, to err from the truth; and therefore felt it incumbent on him to honor his father's God alone.

Having resolved to fully follow his father’s god, he then prays to discover who this god really is.

Accordingly he called on him with earnest prayer and supplications that he would reveal to him who he was, and stretch forth his right hand to help him in his present difficulties. And while he was thus praying with fervent entreaty, a most marvelous sign appeared to him from heaven, the account of which it might have been hard to believe had it been related by any other person. But since the victorious emperor himself long afterwards declared it to the writer of this history, when he was honored with his acquaintance and society, and confirmed his statement by an oath, who could hesitate to accredit the relation, especially since the testimony of after-time has established its truth? He said that about noon, when the day was already beginning to decline, he saw with his own eyes the trophy of a cross of light in the heavens, above the sun, and bearing the inscription, Conquer by this. At this sight he himself was struck with amazement, and his whole army also, which followed him on this expedition, and witnessed the miracle.

The narrative goes on the relate that Constantine was directed that night, in a dream, to construct a new battle standard and to paint this symbol on his soldier’s shields. This would be called the Labarum, the exact form of which is not entirely clear from the Latin but probably included a golden spear with a crossbar upon which was mounted a panel featuring the Greek letters Chi and Rho, the first two letters of the title Χριστός (Christos). Lactantius, writing earlier in his On the Deaths of the Persecutors, mentions only the dream and not the vision, and this has led many to believe that Constantine or Eusebius fabricated the story. For my part, I find it interesting that Eusebius, a believer in miracles himself, anticipates that readers will doubt his story, and he emphasizes that he himself would have been incredulous had the emperor not told it to him personally and affirmed the truth of it by formal legal oath. Constantine didn’t have any real reason to lie; at the point he told the story had been the emperor for decades already and few of his contemporaries would have doubted that some powerful God or gods had made him so even without the story of the vision.

Further insight into Constantine’s religious views can be found in his Oration to the Saints, a unique work combining amateur philosophical declamation and sermon. The speech is recorded in Eusebius’ Life of Constantine. While it is unclear exactly when it was delivered (H.A. Drake gives a range of dates) it can safely be taken as typical of the emperor’s mature thought regarding religion, and belongs to the period after his most signal military triumph. Of note is that while Constantine regards Christianity as absolutely true, he doesn’t regard paganism, at least in its monotheistic tendencies, as wholly false. Chapter 16 and 17 give arguments from the Old Testament as to the coming of Christ, for example, while 18, 19, and 20 reference the Erythaean and Cumaean Sibyls and Virgil as being similarly prophetic to the same end. Taken as a whole, the sources paint a picture of man who, while not any sort of original or speculative philosopher, had clearly thought a great deal about religion under the influence of a diverse circle of educated men, and seems to have come to the conclusion that the Christian God was in fact the One Supreme God his own father had been worshiping the whole time in ignorance. This notion, that paganism in its monotheist form could in some way be reconciled to Christianity as a kind of inferior edition of the truth, tolerated and even patronized in the interest of concord, would come to inform many of Constantine’s religious decisions.

Constantine would indeed obey his prophetic dream. His army would march under the banner of Christ against Maxentius, whom we are told had employed all the resources of Roman sorcery against him in turn. Constantine crushed Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, October 28, 312, with his enemy drowning in his heavy armor as he attempted to flee across the Tiber. Maxentius had had an complex relationship with the Church in Rome, alternately persecuting and tolerating it, but with his death it was safer for the new regime to simply depict him as a tyrannical persecutor in the mold of Galerius. Maxentius would be the last Roman Emperor of any kind to live in Rome. Entering the city, Constantine celebrated a kind of triumph but in keeping with his new sensibilities did not perform the customary sacrifices to the gods.

Shortly thereafter, in early 313, Licinius arrived in Milan for a summit, and he and Constantine jointly offered a statement of universal religious toleration for the empire. This act, known to history as the Edict of Milan, went further than Galerius’ earlier deathbed cessation of persecution and prescribed not only freedom for Christians, but the return of their personal and corporate property. This statement was in keeping with Constantine’s general outlook as it would remain for the rest of his life, privileging Christianity while sanctioning or even subsidizing pagan practices that were not antithetical to Christian beliefs. For the next decade, Constantine would patronize the Church and identify ever more closely with the faith, thought with two important caveats. It is first of all unclear at what point he technically became a Christian, famously deferring baptism until he was on his deathbed. And second, despite making Christianity the most favored religion, it was never actually the official religion of the empire. Pagans of all types, Jews, and others continued to form a substantial collective majority, and the Christian community itself was by no means wholly of one mind, as painful experience would show Constantine.

Many traditional pagans looked askance on the changes Constantine supported, and with the Church largely on his side, Licinius, having defeated Daza later in 313 and now the major power in the east, naturally gravitated toward the bases of support least favorable to his rival. War between the brothers-in-law gradually became inevitable, and Constantine defeated Licinius in 324, capturing his eastern capital, the old Megaran colony of Byzantium. Recognizing the advantages of the underutilized, strategically-situated port city, and increasingly realizing that Rome, with its old pagan associations, was not the proper staging ground for the changes he wanted to exemplify, re-founded the city as Constantinopolis, the City of Constantine, and made it an explicitly Christian capital.

Constantine had finally triumphed over the last of his rivals to become the sole emperor of the Roman Empire, defeating his enemies in the name of the Christian God in whose name he now ruled. He had set himself up as the protector of the Church, a patron of religion as befitted his status as emperor. But as he was soon to discover, the religious concord he sought to instill in his empire would not be so easily achieved, and outside of his charmed circle of Classically educated fellow believers were a number of powerful men very much possessed of their own ideas about the role of the Church in the empire. Constantine would face a new sort of conflict, one in which the nature of battle was very different from what he had previously encountered.

CONTINUED IN PART II

For Reference:

Barnes, T.D. Constantine and Eusebius. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, MA. 1981.

Brown, Peter. The Making of Late Antiquity. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, MA. 1993.

This is the light, well-read and confident way in which history should be told. I'm looking forward to part two.

This was really excellent. It's great to see Aurelian Restitutor Orbis get the attention he deserves. He's one of my most-admired historical figures. I wrote a spec pilot for a TV series about him but 'Make Rome Great Again' didn't sell in Hollywood....