Politics is a dangerous business. Even a leader as universally beloved as Donald Trump- best known for his scene-stealing role in the classic family Christmas film Home Alone 2- has his detractors, at least two of whom have tried to murder him for reasons immediately deemed too bizarre for law enforcement to be interested in investigating. But if things seem bad now, it’s important to remember that the levels of violence in public life today are historically so minuscule that our forbears would accuse us of being low-T betas, fit only for a remedial course at Hustlers’ University. Comparatively speaking the past was a war zone. This was especially true in the Old South, and still more so on the frontier, the Golden Age of Violent Redneckery.

Andrew Jackson was never a man about whom one could hold mild opinions. He’s the kind of leader whose face gets put on money while those same dollars are solicited in efforts to posthumously cancel him. He was a man of enormous violent energy, who fortunately lived in a time and place when such masculine drive could be mostly directed outward in ways which worked to the long-term betterment of his country. 1828 America elected him President; 2028 would probably find him in the middle of an indefinite prison sentence, the cell-door key having been safely deposited in the Marianas Trench. Things have changed a great deal in two centuries, not always wholly for the better.

Jackson had a hard life, growing up in poverty in the freshly-settled South Carolina uplands, raised by a widowed mother. A combat veteran at 13, a POW and an orphan by 16, he emerged from the horrors of the Revolutionary War in the southern backcountry determined to move west and rise in the world. The clearest path forward was through the law, but paradoxically, being a lawyer on the Tennessee frontier meant being drawn into extrajudicial violence at frequent intervals. His 1806 duel with Charles Dickinson is well known- a minor dispute over a horse race bet devolving over six months of backbiting into slurs against Mrs. Jackson and a challenge. Jackson allowed Dickinson to fire first, which would offer Jackson more time to aim. This did give Jackson the opportunity he needed to drill Dickinson through the abdomen, but the unhappy catch was that Jackson took a round to the chest in the meantime. Dickinson died in agony the next day, leaving behind a wife and infant son. Jackson took a bit of a hit to his reputation over this, but for him, matters of honor were life and death affairs, and he had no regrets about the widow and orphan he’d produced or the .50 bullet that would remain bouncing against his heart for the rest of his surprisingly long life.

He would probably be pleased to learn that there is an entire Wikipedia page dedicated solely to his personal violence.

Such was the world of the southern frontier. It was a place where Scots-Irish notions of retributive violence, a slave system necessitating a constant pose of preening toughness among masters (and would-be masters) a very much contested contact line with powerful native tribes which demanded vigilant militarism, and spectacularly copious amounts of grain alcohol all blended together to produce a society that was both dynamic and destructive. The legacy of all of this still forms much of the cultural infrastructure of the South.

Jackson was an alpha in this world, the sort of man who naturally made enemies, some of whom started as his close friends and protégés. Perhaps his most positive trait was his tendency to recruit talented young men into his circle, mentoring them and helping them achieve status in both local and national affairs. Fatherless and self-made himself, he genuinely enjoyed this role, and an entire generation of politicians, including multiple presidents, would owe their careers to Jackson’s patronage. However, these relationships were often tense, strained by competitive ambition among the fierce young men he cultivated, and when they didn’t flame out, they could end in violence.

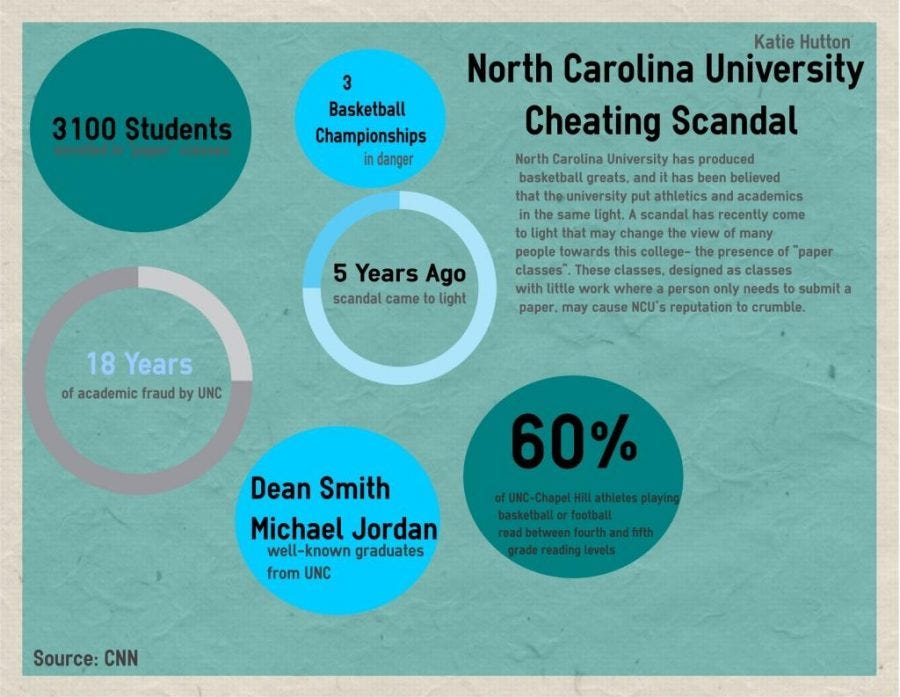

Among Jackson’s circle was a young man from North Carolina named Thomas Hart Benton. Benton had something of a checkered past, having been expelled from UNC for stealing, and he had made his way to Tennessee under a bit of a cloud. Jackson didn’t hold this against him; few men on the frontier hadn’t left behind something unpleasant, and they became acquainted with each other when Jackson was a district prosecutor and Benton a young lawyer.

Their relationship solidified during the then-famous Patton Anderson murder trial. Anderson was a violent, drunken blowhard who had gotten into a horse-trading dispute with the Magness family. Threats were made and Anderson ended up shot to death on the street in Knoxville in 1810. As it happened, Anderson was a business partner of Jackson’s who, incensed by the death of his friend, assembled a team of prosecutors to go after the Magnesses. Benton was a junior member of the crew.

The probable course of events that emerged at the trial was that the Magnesses, fearing Anderson’s very plausible and public threats to murder them, basically baited him into drawing a knife on father Jonathan Magness, whereupon son David shot him with a gun prepared by his brother Perrygreen. In other words, the Magnesses created a scenario where they technically plotted Anderson’s death but did so such that they could just as technically claim self-defense. Fortunately for the Magnesses, they were ably defended by the best lawyer in Tennessee, Felix Grundy and Jackson himself delivered the defense an own-goal when he took the stand as a character witness for the deceased and basically described the Magnesses as just the sort of people Anderson would want to kill. The jury basically split the difference, convicting the Magnesses of the far lesser charge of manslaughter. This meant they would be branded with the letter M on their hands and be forced to pay court costs. When they couldn’t come up with the money, they were jailed, that offense being far more serious on the penurious frontier than shooting a quarrelsome alcoholic, of which there was no shortage.

Jackson was pleased with Benton’s performance despite the loss and eagerly advanced his prospects. By 1812, Jackson had become major general of the Tennessee Militia, the most important military command in the state, and was serving in that capacity when the eponymous war with Britain began. In January of 1813, Jackson, at the head of 2,000 volunteers, marched off to New Orleans to defend against an expected British attack. Benton was by his side as a staff officer.

Things proceeded normally enough until Jackson arrived at Natchez. There, he found a waiting message from the Secretary of War, thanking him for his service and informing him that he was to disband his militia and return home. His supplies were to be forwarded to Major General James Wilkinson of the regular army, already in New Orleans. Jackson was quite naturally confused and angry at this, not least because Wilkinson was a barely-disguised traitor on the Spanish payroll, who’d earlier been involved in the Burr Conspiracy that had almost ensnared Jackson as well. But to disband his militia hundreds of miles from home meant that his men would have to return on their own dime, which would be a disaster for poor frontier farmers. Jackson wasn’t having it. Not for the last time, he ignored orders and marched off on his own initiative.

Fortunately, we’re long past the days of greedy, sellout, disloyal generals.

This wasn’t without risk; apart from the insubordination, Jackson would have to feed 2,000 men from his personal funds and hope that he could sort the matter out later. His decision could well have not only bankrupted him but ruined his career, or even see him facing court martial. But Jackson, for better or worse, was a man of honor, and he led his men home. It was here that Jackson earned the nickname ‘Old Hickory,’ after that unbreakable pillar of a tree.

But if his will was unlimited his finances certainly weren’t. Jackson was essentially gambling that the federal government would see the wisdom of his position and reimburse him. Someone would have to go to Washington and sort things out, a delicate mission that would determine Jackson’s future. And for this task he chose Benton. It must have seemed to the young man that this was his ticket to the big time. Securing Jackson’s position would more than secure his own as well. One can well imagine the prospects that must have been dancing around in his daydreams- LTC Benton as Congressman Benton, Senator Benton, Governor Benton..? And indeed, after protracted negotiations he was able to successfully complete the mission and get the War Department to assume Jackson’s debts. He returned to Tennessee full of pride, only to discover than in his absence everything had gone horribly wrong.

The problem began with his younger brother, Jesse Benton. Nowhere near as talented as Thomas but just as ambitious, he had gotten into a dispute with another of Jackson’s followers, William Carroll. A theme that runs through all of these accounts is the odd warping of masculinity at its edges. In the hyper-manly world of frontier life, largely unleavened as yet by the ameliorative effects of the Christianity of the Second Great Awakening, the constant need for macho display worked its way along a kind of horseshoe until it became vaguely feminine. The toughest men of the age spent an extraordinary amount of time on the pettiest gossip, sending endless letters to one another on the subject of who said what about whom, or demanding explanations for rumors, or otherwise just facilitating empty cattiness that would embarrass a sorority girl. Unfortunately, these episodes ended not in social media meltdowns, but pointless and destructive violence.

Jesse Benton called out Carroll, who asked Jackson to be his second. To his credit, he’d originally tried to stay out of the dispute, but Jesse Benton proved so obnoxious in the meantime that Jackson changed his mind and backed Carroll, despite the fact that brother Thomas Benton was at that moment fighting the government on his behalf. Honor was everything to Jackson, and believing Carroll in the right, he ultimately felt bound to support him, regardless of the consequences. These would prove more grave than he could have imagined. The actual duel was at least less a tragedy than a farce. Both men fired; Benton missed, but Carroll’s aim was true. The wound wasn’t life threatening because at the last moment Benton flinched and turned around. The bullet hit him squarely in the ass.

From The History Channel documentary.

This was the situation that Thomas Benton faced on his return to Tennessee, the man he’d rescued from oblivion facilitating the humiliating wounding of his brother in a stupid quarrel. Unfortunately, the best way anyone could think of to resolve the situation was another quarrel that was even stupider. Benton probably understood that his brother had been in the wrong, but was more or less forced by the prevailing code of violent retribution to publicly rebuke Jackson for his role in the fiasco. Jackson likewise must have realized that Benton was honor-bound to defend his brother, but couldn’t very well endure the younger man calling his character into question. That they had been so close before only made it worse, and Jackson’s crew of hotheads egged it on. Things finally descended to the point, after weeks of mutual slander, that Jackson declared he would horsewhip Thomas Benton on sight.

This was not an invitation to a duel. Horsewhipping or caning was a public physical rebuke one dished out to someone deemed a social inferior. Gentlemen traded shots; beatings were for slaves or children. Jackson was so angry at Benton that he essentially declared him beneath contempt and meant to cement that status into the public consciousness by flogging him in the street. The Bentons, naturally, had no interest in enduring such an assault, and let it be known they were armed and prepared to kill to defend themselves.

So the matter stood in Nashville on September 4th, 1813. Jackson rode into town from his plantation about nine miles away, ostensibly to get his mail from the post office there. With him was his close friend and relation by marriage John Coffee, a hulking bruiser of a man of the type one generally has tag along for errands other than picking up letters. Jackson and Coffee hitched their horses at the Nashville Inn and learned there that the Bentons were at the City Hotel, one side over on the town square from their location. The post office was directly across, meaning that their path there would take them past the brothers.

Jackson and Coffee walked to the post office and, sure enough, the Bentons were sitting there on the front porch of the City Hotel, glaring at them. Jackson and Coffee glared back. And then . . . the pair kept walking. They picked up the mail and returned, but this time, only Thomas was sitting outside. It was only then that Jackson made his move.

Why he didn’t attack Thomas Benton “on sight” as he’d proclaimed is a matter of conjecture, but it may have involved some hesitancy on his part to needlessly risk harm to Coffee over what was ultimately a pretty meaningless dispute. With both brothers there it would immediately have devolved into a shootout, but Thomas alone meant Jackson could face him one-on-one with Coffee only needed if Jesse returned and jumped in. This interpretation is borne out by the what happened next. Jackson rushed at Benton brandishing his horsewhip, calling him a damned rascal. Benton went for his pistol, but apparently it was not ready at hand such that Jackson was able to drop his cowhide and draw his own gun first. Benton raised his hands and started to back up, cursing Jackson. Jackson followed and they both entered the lobby of the hotel. Coffee did not immediately follow.

The situation must have been immensely awkward. Jackson had Benton at gunpoint, but the latter was clearly unarmed with his hands in the air. He couldn’t shoot him, but he couldn’t drop his gun either. The lobby was full of people and everyone must have been staring at the spectacle. Fortunately for Jackson, the standoff didn’t last long. Unfortunately for him, this was because Jesse Benton jumped out from a concealed position and shot Jackson in the back with a double-loaded pistol. One might speculate that there were echoes of the Mangess’ plan in what happened, the dangerous Jackson drawn into a scenario where he could be shot in the back in a way that could be plausibly argued was self-defense.

All hell broke loose. True to form, Jesse Benton failed to kill immediately the man he was shooting from behind from a few feet away. One bullet entered Jackson’s left shoulder and another broke his left arm. He went down, but not before his own gun discharged, missing Thomas Benton but close enough that the igniting powder burned his coat. Thomas pulled his gun and shot quickly at Jackson, but the latter had fallen so fast that he missed as well. Coffee burst into the room and opened fire, missing Thomas but causing him to backpedal such that he tumbled backwards down a flight of stairs. As it happened, a friend of Jackson’s named Stockley Hays chanced to be in the lobby when the fight began, and he drew his sword cane and stabbed at Jesse, only for the blade to hit a heavy coat button and break. Jesse aimed his remaining pistol at Hays and pulled the trigger, but the gun misfired and Hays was unharmed. In the confusion the Bentons fled. Jackson was taken to a hotel room.

The future president was grievously wounded, blood pouring out of his shattered shoulder. The doctors summoned collectively agreed that Jackson’s arm needed to be amputated. Before losing consciousness Jackson apparently threatened them with death if they did so, and not willing to risk it, they bandaged him up as best they could. He ruined two mattresses with bleeding before they managed to staunch the flow. Men marveled that he survived, but such was the iron constitution of Old Hickory that they may as well have shot the actual tree.

None of this attracted any interest from law enforcement, nor, in a town of around 4,000 people, did a shootout involving one of the most prominent men in the state make the news. Years ago, when I first researched this, I recall the first mention of the fight in the media being an open letter from the Bentons published about a week after the fact wherein they lamented the death threats they were receiving from Jackson partisans. That’s not to say that public opinion wasn’t engaged. In general, while people were tolerant of personal feuds extending into homicide attempts, the overall consensus seems to have been was that this was all a bit much. Jackson was 45 and held an important military command during a war. Even by frontier standards he was a bit old for stuff like that. Brawling in a hotel lobby was worse than criminal; it was undignified.

Jackson, as always, cared nothing for the opinions of the crowd. He’d upheld his honor and had no regrets despite almost dying for essentially nothing when his country needed him. Indeed, shortly after this Jackson was summoned from his sickbed to avenge the Fort Mims Massacre and lead the Tennessee Militia into the field once more. His arm was still in a sling at Tallushatchee and Horsehoe Bend, and he was not wholly himself even at New Orleans.

For their part, the Bentons departed Tennessee amidst the controversy and threats for greener pastures. Thomas settled in the Missouri Territory, where he once again reinvented himself as a man of consequence. Indeed, once Missouri became a state, he became one of the most important champions of westward expansion in the Senate, a voice for the common man very much along the lines of Jackson’s program. And that leads to perhaps the most unexpected part of the story.

Benton and Jackson met again when Jackson was elected to the Senate and later as president. The former friends-turned-deadly-enemies found they still had a lot in common, and gradually, what started as an alliance of convenience became a rekindled fellowship. At one point, the bullet that Jesse Benton (who never stopped hating Jackson) had fired into his arm migrated under Jackson’s skin to the point where it was just below the surface. Jackson had a surgeon remove it and mailed it to Thomas as a symbol of reconciliation.

They remained good friends until Jackson’s death in 1845. Thomas Benton, the man who’d so violently quarreled with him, eulogized him profusely, both at his funeral and in his copious memoir, Thirty-Year’s View. Of their dispute, Benton graciously noted only the following:

His temper was placable as well as irascible, and his reconciliations were cordial and sincere. Of that, my own case was a signal instance. After a deadly feud, I became his confidential adviser; was offered the highest marks of his favor, and received from his dying bed a message of friendship, dictated when life was departing, and when he would have to pause for breath.

He went on to sum up the man with whom he’d had such a turbulent relationship. While the public thought of Jackson as a violent and contentious man, he begged to differ, offering this very personal account as representative of the real Old Hickory:

He was gentle in his house, and alive to the tenderest emotions; and of this, I can give an instance, greatly in contrast with his supposed character, and worth more than a long discourse in showing what that character really was. I arrived at his house one wet chilly evening, in February, and came upon him in the twilight, sitting alone before the fire, a lamb and a child between his knees. He started a little, called a servant to remove the two innocents to another room, and explained to me how it was. The child had cried because the lamb was out in the cold, and begged him to bring it in—which he had done to please the child, his adopted son, then not two years old. The ferocious man does not do that! and though Jackson had his passions and his violence, they were for men and enemies—those who stood up against him—and not for women and children, or the weak and helpless: for all whom his feelings were those of protection and support.

It’s a nice note to close on, that men of such ambition and violent energy, killers and conquerors, could rise above pettiness and pride to reconcile and become once more friends and allies. Jackson and Benton were flawed men, like the rest of us, their particular sins more evident only because they were simply so much more than the common run. But like all of us, they had the ability to rise above those defects of the soul and forgive, the capacity for such being that quality that ultimately divides the civilized man from the barbarian, the focal point of Christian life. It’s a pleasant thought that even such rough creatures as those can point men of a more placid age to a better path.

This is a great example of why Jackson is my favorite of the U.S. Presidents. The man's life is both wild and fascinating, chalk full of so many interesting facets that every time I read about him, even in relatively short form as is the case here, I feel like I come away with a mountain's worth of new and gripping information. I find myself in disagreement with him almost as often as I find myself in agreement, and that honestly just makes me like Old Hickory all the more.

Andrew Jackson paying off the National Debt easily makes him the best President we've ever had.