Introduction to Issue 1

Featuring commentary on:

I invite you to subscribe to them all.

This is an experiment. In some ways, this project is a response to the recent small dust up around a note posted on the subject of curtailing participation on Substack by writers with under 1,000 subscribers- more on that below. But it is also a long-running, back-of-the-mind germinating idea related to how I might both progress as a writer and offer something to my paid subscribers beyond my normal content. It seems to me that one thing lacking on Substack, at least as far as I have been able to find, is a true literary review, or at least, one dedicated specifically to showcasing those writers who have talent but lack exposure, which we can arbitrarily designate as those with below a thousand subs. Hence the proposed title for this project, Sub Mille

I have in mind something like the digest (currently on hiatus) produced by John Carter and other great aggregations like New Right Poast, but I want to take it a step further. While those fine publications put great work on blast (and, full disclosure, have sometimes condescended to feature this author), I mean to go beyond simple mention and overview to offer a critical and comparative understanding- a more thorough focus on fewer authors, reviewing their work and presenting it for what I hope is a wider, or at least different, audience. I plan to focus overwhelmingly on authors who currently have fewer than 1,000 subscribers, but I will occasionally feature those with more. Most of this will involve newsletters, but occasionally lengthy notes that become the subject of wide discussion will be featured. To that end-

Controversy and Consensus

Morgthorak the Undead and Adam Wilson- CONTROVERSY; Kruptos, et al.- Consensus

In his piece, “Woke communists seek to control Substack,” Morgthorak takes to task James Richardson’s recent note advocating exclusionary measures to screen out writers with fewer than 1,000 subscribers, on the grounds that allowing in everyone needlessly complicates the efforts of more prominent writers to identify and groom talent. Richardson offers that this is how any successful community operates, communities which are necessarily “hierarchical, gatekeep entry, enforce rules, and create vertical obligation (master, apprentice).” Morgthorak in particular takes issue with this, and Richardson’s overall elitism, while at the same time labeling this worldview “communist.”

Here is where I feel some refining of terms might be in order. I agree with Morgthorak that Richardson’s ideas, if taken up by Substack management, would destroy the platform. But while I think Richardson’s instincts are authoritarian, I do not think they are communistic. A communist would advocate for control and censorship, but also a rigid ideological conformity that Richardson does not mention. His viewpoint is neoliberal; the good writers are the ones the experts like, and the experts are those writers revealed to be great through market, rather than ideological, forces. His view of art is not that it exists to serve the masses or advance a revolution, but that it is a commodity, the value of which is determined by the same means as the price of eggs, and those able to generate such value are the only real artists, by definition. This seems to be the frustrated subtext of Richardson’s original note- he, a PhD and unaffordable corporate consultant, unaccountably (to him) has fewer than 1,000 subscribers, and he can only attribute this to some distortion in market forces. All the people writing about their crazy cats amount to “noise” that prevents him being properly noticed by and uplifted to the ranks of his betters.

There is also the problem of the term “community.” Both Morgthorak and Richardson seem to agree that Substack is a community, disputing only what sort of community it should be. But is that the best way to think of it? Adam Wilson, in his “Labor, leisure, service, and belonging,” offers a critique of the concept of community being offered as a marketing strategy, taking advantage of people’s desire to belong in order to profit. Certainly, one might offer a critique of Substack along those lines; sensitive, artistic souls long for a sense of connectedness with other like souls, and in a lonely and disconnected world, the internet can seem to offer some facsimile of that. But as Wilson points out, real communities are defined by a sense of belonging unconnected to belongings (he explores that distinction in the meaning of the word in a way I found truly insightful). Our relations to each other must transcend the material. Substack, to avoid a word he finds “flaccid,” is less a community than a platform, an agora or shopping mall, where one socializes and conducts business, but any real sense of community must mean more than that. Community is that which one would sacrifice for, that from which one draws one’s identity. Would any of you readers go to literal war for Substack; if the website went down, would you cease to be who you are? I think that understanding what we are doing here is essential to getting the most out of it, whether that means ruthlessly climbing Mount Checkmark or writing installment 34 of your series on Gay Rappers of the Illuminati to your literal dozens of fans.

On a less contentious note, Kruptos, joined by Johann Kurtz, The Black Horse, Riley S., and Christopher Brunet, hosted a discussion in his Christian Ghetto series on building resilient communities able to resist the dark trends on the horizon. The post is also a gold mine of links to the respective participants’ works, all of which are brilliant and deserve to be shared. Please take an hour or two to explore; you’ll be grateful for the experience. Kurtz’ idea that talented dissidents should join liberal organizations is one I agree with as a matter of tactics, and though I would hesitate to boast of any talents I am quite busy climbing the greasy academic pole in my own career, with the end in mind of earning the credibility and connections to be of service to frens. It would be useful, I think, for such people to find some way to signal to each other, to form nodes within the networks of managerialism so as to be able to direct up-and-comers in the right direction- frens up, enemies out. Perhaps someone can take one for the team and become an HR director; the rest of us can set up a Yasukune Shrine for such spirits.

For those brave gyukusai who gave all to work in HR.

Culture

Rachel Haywire, Alexandru Constantin, and Sarah Eckel- Loneliness

Along the lines of people seeking out community, I went down a bit of a loneliness rabbit hole these last few weeks on Substack, reading several entries on the subject, some of which are older, but all still relevant. Substack and places like it are interesting places for discoursing on solitude, for the reason that many writers are profoundly lonely people. After all, if they had people on hand to discuss their favorite subjects, they’d be talkers instead; writing is a way to put a message in a bottle and send it floating onto the internet, hoping your message will compel someone to rescue you from your island. But is it any better for non-writers? It would seem not.

Haywire’s “Why Can’t We Be Friends” focuses on the act of acquiring friends, and how the internet, with every promise of making the process easier, actually complicates things and reduces friendships to sterile rounds of texting and cat pictures. It’s a strange situation that limits human interaction to an interplay of media representations; lost is nuance, non-verbal communication, physical intimacy, and all the subtleties of sharing a space with another. Some, especially in the wake of Covid, seem to have permanently retreated into this ether. Haywire doesn’t delve into the underlying psychology behind this, but I suspect a lot of the unwillingness to meet in person comes down to fear, a deep-seated insecurity about how one presents to others, the result of an internet-warp-field distortion about how others live and how one measures up to them. Am I pretty enough, am I rich enough; will people discover that I’m not that interesting in person? I’ve seen firsthand, recently and publicly, how those fears can destroy the potential for positive connections in real life. So long as we succumb to the temptation to retreat to the screen we will never overcome this fear, which will endure as long as we prefer comfortable manipulation to a risk of judgment.

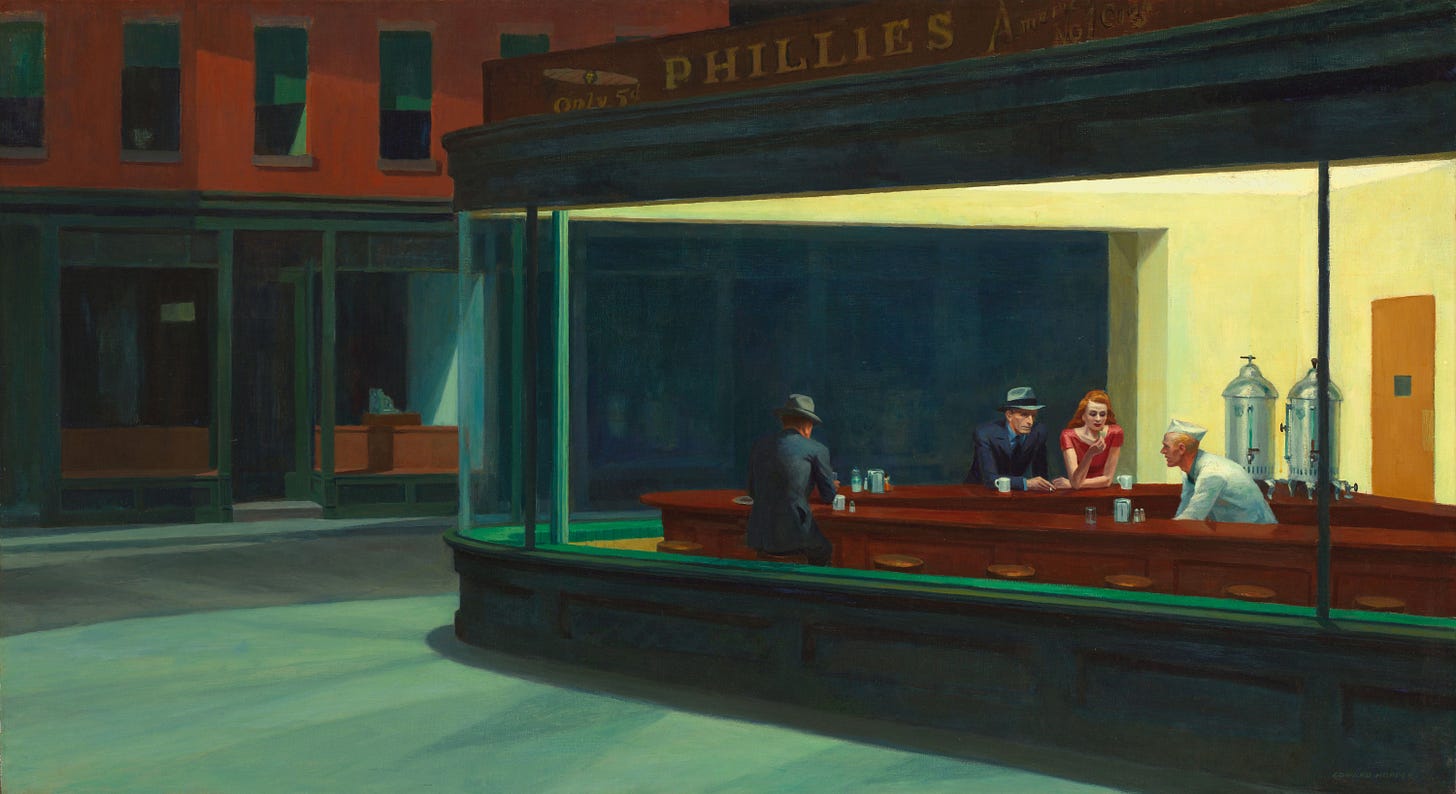

Through a restack, I discovered an older post by Alexandru Constantin, “A Pint With Friends,” that deals with similar issues. While Haywire’s piece focuses on activity, Constantin’s deals with place, specifically the “third places” of Ray Oldenburg, those settings that offer a respite from the stresses of work and home. I was reminded immediately of Hemingway’s “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” in his description; in my own life, I have been each of the waiters and the old man himself. While Haywire’s central problem is a lack of people willing to meet in person, Constantin explores the related issue of there being no place to do so. The hubs of community life are disappearing, out of convenient reach of those with significant work and family responsibilities, along with different social and economic norms that drive us indoors at night like penned-up sheep. People socializing together outside the office, that zone of control, would always be problematic in a system designed to grind down the private associations. Burke’s ‘little platoons,’ where people can discuss the foibles of the regime and cohere under some sense on independent normalcy, run a real risk of turning into zones of resistance. Being able to buy things from your couch resolves any economic hesitancy for the system to keep you under house arrest, and so, that is where we find ourselves.

Even when one tries, it can be difficult to find a third place. A mention from Constantin led me to Sara Eckel, who notes this in her “The Loneliness of the Modern Restaurant,” which explores how the settings that used to facilitate the kinds of interactions necessary to facilitate friendships and community get ground down by the logic of capitalism. The friendly neighborhood pizza place becomes the corporate revenue extraction engine which has accomplished its mission the minute it has your money and can immediately send you out the door with your rapidly congealing meatball sub. Something as well about the scientifically-engineered ‘friendly’ atmosphere places one in the uncanny valley; somehow the strange décor of Tony’s is more welcoming than the clean lines and shiny metal of its replacement. Perhaps it’s the knowledge that the décor is the means to a different end in the latter than the former, one being to make the patron feel welcome, the other to calm misgivings to facilitate transactions.

What is the solution to the problem of loneliness? Courage. Unless we would be a nation of hikikomori, we must never be satisfied with a society that hounds us from a public presence. As writers, this is especially true. Looking at the lives of the greats, one consistently sees them as members of fellowships, clubs, guilds, associations, but above all, networks of talented and sensitive friends who were able to serve as sounding boards, fair critics, and support systems. Lewis and Tolkien had the Inklings; there was the interwar modernist scene in Paris; Ficino and his patron Il Magnifico spoke freely in the Florentine academy, etc. It should be the same for us as well. Substack is a great place to get acquainted; real life is where we become actual friends.

Back when loneliness was the biggest problem in Chicago

Academia

Jon and Dan Allosso- The Perils of Reductive Thinking

Academia, a few generations ago, might have proven an intellectual haven for aspiring writers or those interested in the liberal arts more generally. I certainly can’t have been the only one who hoped to leave provincialism behind when I went off to State U. in search of the scholarly brotherhood I was sure to encounter. Sadly, the norms of neoliberal life that have stripped mainstream culture of its depth and meaning have long since engulfed the academic world; some would argue they began there. Thus we find the replication crisis rearing its ugly head again in Jon’s “On the Funny Failure of Psychology,” where he details the fallout from recent revelations that the field of experimental psychology is not just rife with fraud, but fundamentally illegitimate, which elicited a collective ‘meh’ from the relevant parties, who simply went on doing what they were doing, as it in no way became less profitable for its having been shown to be fake. The managerial state needs things like experimental psychology to be true; the people behind the system need the human spirit to be quantifiable, and a ‘science’ that gives them some way to describe humans in terms of inputs and outputs is essential to their mental framework. One need only read James Scott (Seeing Like a State) or Rene Guenon (The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times) to understand this characteristic of the managerial class.

I suspect that something like this is behind the tendency to ignore the realities of the lives of common people in favor of abstractions. Dan Allosso, in “Holbrooke’s Lost Men,” explores this by way of a brief synopsis of the work of Stewart Holbrooke, author of the 1946 Lost Men of American History. Writing in a time where titans like McArthur and Stalin seemed to bend the fate of nations to their will, Holbrooke offered the counter that it was often lesser known, idiosyncratic personalities, or sometimes entire groups that entered and left history in the blink of a historical eye that worked to make things happen. Sometimes one sees the surfer and ignores the wave; this is entertaining, but does little for understanding why things are in motion, nor does it prepare one for the crash. Allosso has a lot of other interesting things to say; do check out the rest of his work for a personal look at the state of the contemporary academic world. If you have any illusions about academics floating on some cloud far above the realities of globalist capitalism, allow him to disabuse you.

Scott lays out how the problems of the modern world began with efficient forest management.

Big Tech and Its Discontents

Alexander Hellene and Neoliberal Feudalism- The Great Glass Eye, at once all-seeing and fragile

Hellene, in his “The Perfection of the Unnecessary,” opens with a postmodern take on a no longer funny joke- how many websites does it take to screw in an iLightBulb? The answer is actually fairly sinister and the laughter you hear is the distant chuckle of a California tech oligarch discovering a novel form of rent-seeking that will enable him to drain a bit more juice out of our financialized and overleveraged economy. Planned obsolescence is an old concept, but one which has taken on new life as the logic of unbridled yet managed capitalism plays out to its conclusion. Ownership becomes ever more nebulous and contingent, but as we become a nation of renters and subscribers we also, paradoxically, have less and less invested in the system every day. A man’s home is his castle; a man’s apartment is his rented mule. As the Roman Republic discovered to its great detriment, men without property are the natural constituency of warlords, and when a res publica becomes a res privata, the loyalty of the masses needed to sustain the system disappears. There is much more to learn from this piece, so do check it out.

The ubiquity of financialization would be impossible without the great tech panopticon, and thus we segue to Neoliberal Feudalism. NF technically has over 1,000 subscribers, but as he has two publications, I will do some complex long division in order to shout him out here. His “Profiles in courage” series continues this month with a long take on Julian Assange. I must admit I only knew the bare outlines of Assange’s story (I actually thought he was French for some reason; he’s Australian) and the essay is a great introduction to Assange’s history and philosophy. Assange seems to have run afoul of nearly every government on Earth, and being unable to make it to Russia, is now imprisoned in the Free World awaiting a probable stint in the horrific American oubliette known as ADX Florence. NF disagrees with Assange’s commitment to total transparency and faults him for not exploring more deeply the forces behind the scenes, which for NF are Rothschild bankers. He also critiques Assange’s seeming reverence for the masses, and points out, correctly as I see it, that there has never been a time, nor will there be a time, when the masses are engaged and committed philosophically to the work of maintaining a democratic form of government. While I would not go as far as NF in my assigning ultimate mastery to a cabal of bankers (I think the forces behind the scenes are ultimately not as coordinated and coherent as they appear), I largely concur with the substance of his very thorough take, including Assange’s advocacy of cryptocurrency. Do read it and decide for yourself.

This image is from a Vice article, “The Long Suffering Partners of Crypto Bros Hate Their Lives Now.” One wonders why they loved them before.

Fiction and Poetry

Shaina Read and Dan Ackerfield –A bit of the uncanny

I will confess that I do not read enough fiction. What I do read tends to be old and time-tested. I hope to remedy this lacuna in my life by reading and showcasing some interesting and thoughtful work. I was fortunate to have caught the first installment of a series by Shaina Read, “Chattel,” that looks promising. The title, “It Ain’t a Coyote,” was what grabbed me; as Substack’s leading expert in coyote philosophy, I felt like this was something I needed to explore. The story features a rancher encountering what seems, to this point in the narrative, like a classic cattle mutilation scenario. Such stories were a staple of my youth, hours of my life spent in the school library reading about UFOs, Sasquatch, MIBs, and other such Fortean staples. To this day I have a fascination with the paranormal, those phenomena at the intersection of the real and the impossible, shading one into the other, shaping and being shaped by popular culture. To encounter something like that is to meet the uncanny, that which causes both fascination and revulsion by its very weirdness. Read conveys this very well, as her rancher, a very ordinary and seasoned inhabitant of his world, grows increasingly unsettled at the growing realization that what he is dealing with on his ranch is something beyond his comprehension. I look forward to reading the rest.

Dan Ackerfield’s short poem “The Dancer” evokes the uncanny in a more hopeful way. The eponymous dancer is a ghost, the subject of legends within his own Noreni lore. There is the same note of Freudian ambivalence here; the dancer is alluring, but the effect of her beauty is to draw men to their deaths in the water. She is a kind of Lorelei figure, a siren, a representation of the feminine that every man contends with, who inspires a compelling and forceful desire experienced as both longing and fear. The death and longing are incidental and the ghost is oblivious to the ruin she causes; the dancer dances from her own desire to be reunited with her lost love, at which point the author gives hope that upon acquiring a mature relationship the energies she inspires will have found a menaingful outlet, and her haunting will cease, all feelings having been reconciled to their proper end. Read it; it brought to mind Robert Browning and Tolkien’s Beren and Luthien.

This is seriously the only sort of picture that comes up when you Google ‘Lorelai.” Who is this?

Thank you for reading. If I didn’t mention you, please know that for constraints of space I could not include everyone I hope to write about. If this proves successful I plan to release a new issue every month as part of my effort to provide content for paid subscribers. My current plan is to release each issue for paid subs and to keep it paywalled until the next issue comes out, whereupon I will release the older issue to my general audience. This first issue is free to all, and I am very interested in what you think.

Great compilation and summary. Happy to see you diving into the psychology of loneliness here too. Funny enough, I am working on a new piece about the lack of a third place and how to create one IRL. Perhaps the issue is that the online world has become our third place, and that many feel we must choose between the astroturfed world of centralized social media or the alienating world of decentralized media. Neither option is appealing. So, we need something better, and I’m seeking to lay out a blueprint for how to build this.

During this transition from online to offline, I’m glad to have run into you and others in this sphere who I’ve been able to connect with, many of whom you also mention in this post. It makes things less lonely for me. I’m excited for an IRL gathering. I’m excited for our community as a whole.

Got hung up on this Richardson/Morgthorak-thing.

So Richardson is neo-liberal and therefore believes market forces delivers best, but he still wants a formalistic top-down predetermined frame-work for who get what exposure?

That's not "market forces".

The contradiction at least proves he is a real neo-liberal: pro-free market as long as it guarantees him profit and progress, otherwise pro-planned economy (in this case, the economy of viewer's time and ability/desire to sponsor Stackers).

In other words, Richardson is actually a corporatist socialist democrat, if we're to use formal labels and their original meanings.

Then again, all capitalists, neo-liberals and libertarians are pro-"market forces" only as long as it profits them with a minimum of risk and responsibility; being amoral and without any set of ethics above and beyond "Does it benefit me, now?" is an inherent and intrinsical feature of said ideologies.

Actual free market, which is simply evolution but as economics instead of organisms, plays no favourites and always throws up a clique (or a species) which totally dominates and monopolises the economy (biotope/eco-system).

Right. I've got logging to get on with. "Peace out", or whatever the hip phrase is nowadays. Will be back to read the rest later.