N.B. The Librarian recommends reading the following books to accompany this essay:

Metternich: The First European, by Desmond Seward. This book is an extremely readable take on Metternich and his life and times. Everything by Seward, mostly a historian of the Middle Ages, is great, especially his The Monks of War.

Metternich: Strategist and Visionary, by Wolfram Siemann. This is the most through and up-to-date biography of Metternich. The prose is not as polished as in the Seward book (Siemann’s work was translated from German) but it is more exhaustive and scholarly. I don’t necessarily agree with Siemann’s interpretation of Metternich as a Burkean, but it is a must-read for anyone seeking to understand the man and his age.

The Birth of the Modern, by Paul Johnson. This is a great general introduction to the period between 1815-1830. Johnson is not as sympathetic to Metternich as the other authors, but does a wonderful and eminently readable job in describing the time period.

****************************************************************

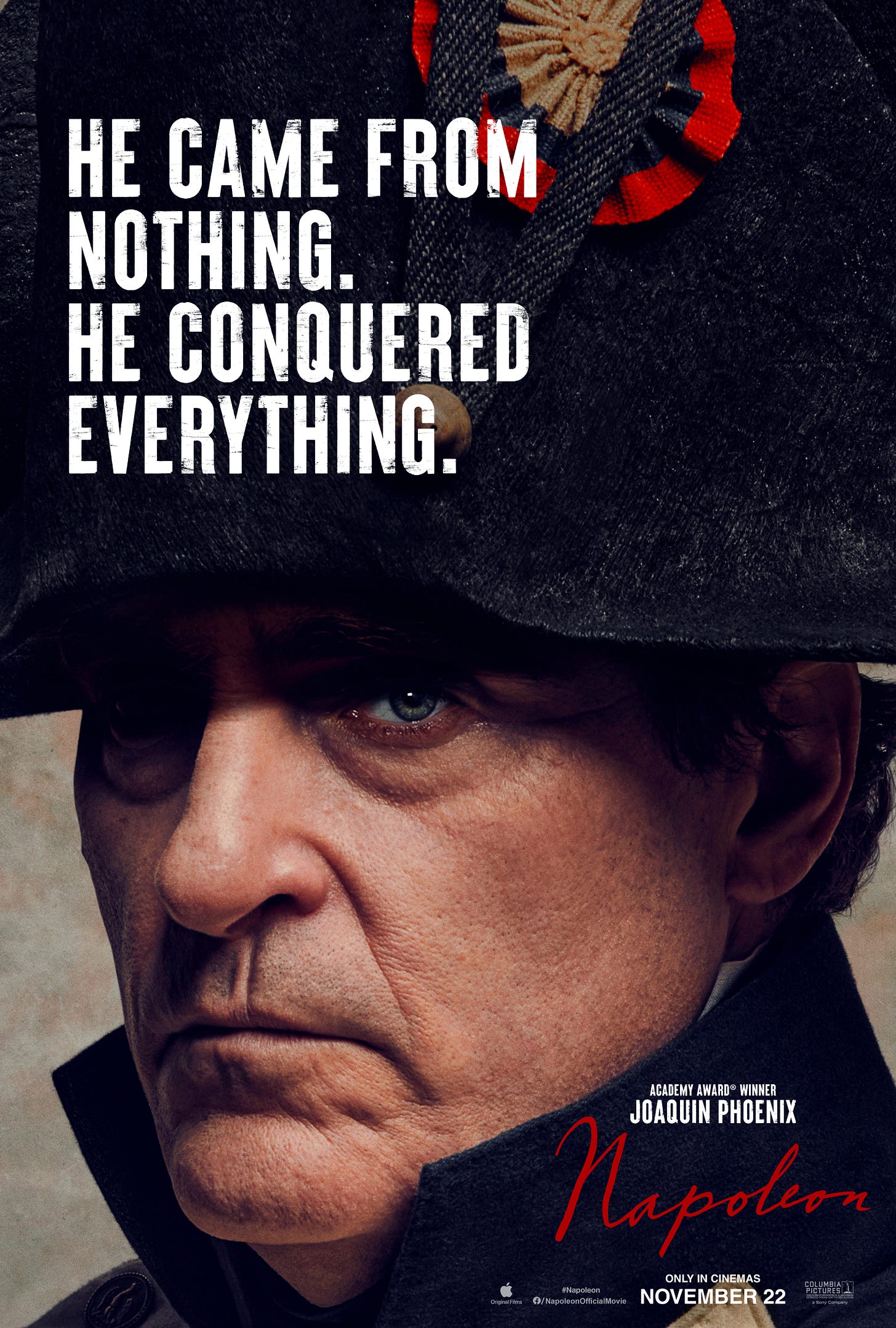

The new Napoleon movie has premiered and thus far the reviews among rightists have not been especially kind.

Nicer than 4Chan, though.

As the curt analysis above complains, it seems the film explores the psychosexual dynamics of Napoleon’s personality in a way certain sectors of the right wing internet find haram. The general consensus seems to be that the movie is a mockery of the actual historical Napoleon, the bold conqueror who imposed his will on Europe, personally leading his Grande Armée of imposing top-G alpha chads through the forces of longhoused betahood that sought to hate on his game. However, this interpretation of Napoleon owes little to history and much to Nietzsche, that most erudite of napofags, who saw the Corsican as one of his beyond-good-and-evil superman-artists, a warlord who made Europe into his personal masterpiece through sheer force of will, painting brushstrokes in blood before succumbing to his own legend and, well, caring too much about actual people, whereupon he was finally defeated by lesser men and exiled. Nietzsche had a thing for ruthless conquerors, as only a man whose most notable military achievement was severely injuring himself getting onto a horse can feel.

It is obvious that in his day-dreams he is a warrior, not a professor; all the men he admires were military. His opinion of women, like every man’s, is an objectification of his own emotion towards them, which is obviously one of fear. “Forget not thy whip”–but nine women out of ten would get the whip away from him, and he knew it, so he kept away from women, and soothed his wounded vanity with unkind remarks.”

I haven’t seen the film and don’t intend to, as when I perused the credits, there was no mention of the name I most wanted to see. A film that had space for “Mid-Shipman #2” but could not include even one scene with the real hero of the Napoleonic Wars is just not worthwhile. And yes, I mean Prince Klemens von Metternich (the film does credit someone as “Austrian Ambassador,” but if that’s supposed to be Metternich, that sucks).

Joachim Phoenix IS Commodus PLAYING the Joker starring AS Napoleon

If you don’t know Metternich well, you should, for he truly was the man of his age most imbued with an iron will, who saw clearly what needed to be done and executed his plans brilliantly and courageously against all odds. He was no ubermensch, merely a man who lived up to and surpassed the ethos of the station into which he was born, who rolled back the tide of revolution and chaos to give the people of Europe peace and order. That they later forsook his gift to them in favor of liberalism and democracy, and thus a century of war and destruction, speaks less of his powers and more of their failure to appreciate what he had done for them.

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar von Metternich was born in 1773 into a noble family of early medieval lineage, his ancestors having played a very long game of ascent within the Holy Roman Empire through the creation of an entailed collection of estates from which members could draw incomes provided they contributed to the family’s rise. Imagine a corporation that exists to provide a living to everyone in a bloodline, provided they stay normal and do something useful with their lives. By this means his father, Franz Georg, had risen to become one of the most important diplomats at the Habsburg court, and young Klemens received not only a first-rate Classical education, but practical experience at his father’s side. There was never any time in his life where Metternich might have become something else, or was given any choice in the matter of the course his life would take. His destiny was as predetermined as any peasant farmer’s, a life of service to the Habsburgs, and his entire youth was spent preparing for that. Such was the least that was expected of any aristocrat of his day, and he more than lived up to his early promise.

Sent away to college in Mainz, on the border of the Kingdom of France, he was there at 19 when the French Revolution crashed into the territories of the Habsburgs. While his father had been sympathetic to the Enlightenment, such that one of Metternich’s former tutors became a leading Jacobin and actual member of the Illuminati (among several of his professors and other acquaintances), Metternich’s direct experience of the guillotine-powered murder-cult of liberté, égalité, fraternité was viscerally horrifying, setting him on a lifelong mission of opposing revolution in the name of tradition and legitimacy. He was given his first diplomatic assignment in Belgium, from whence he had to flee for his life, and then had to watch his ancestral estates in the Rhinelands be overrun and confiscated by the Revolution. Things were not looking good for the long-term survival of the world he knew and loved.

“At least we don’t have some king telling us what to d-”

He was not dismayed however, and the losses only increased his determination to fight back. He was no Hegelian Zeitgeist respektor. Metternich didn’t care which way the forces of history were marching; having decided they were going the wrong way, he would do all in his power to wrench a change in direction. He studied closely the ideologues of the Revolution and the practical application of their ideas. He saw that a plain reading of documents like the Declaration of the Rights of Man spelled out eternal war against the unenlightened world, that no peace was possible with men who regarded your own society as ipso facto illegitimate. He also knew that he and his empire were at a disadvantage. The new French state benefitted from the unleashed energy of thousands of previously underemployed lawyers and administrators now bent to the single totalitarian purpose of crushing the state’s ideological enemies at home and abroad; the Holy Roman Empire, by contrast, was an inefficient hodge-podge of loosely associated territories that had a difficult time staging a meeting, let alone getting onto war footing.

It was a touch confusing, tbh.

At any rate, the Holy Roman Empire’s problems were soon enough solved by way of it no longer existing. It went the way of the French Republic, and by the same hand, that of the newly-ascendant Emperor Napoleon. It is important to note here, pace Nietzsche, that Napoleon did not so much impose his will upon his age as he adapted to circumstances as they presented themselves in a clever way. He was at once possessed of the conservative temperament of his backwater island home and a man of the Enlightenment, having benefitted from the French monarchy’s program of rooting out Corsican nationalism by providing scholarships for the brighter sons of landowning families like the Buonapartes. Napoleon as a youth was thus sent off to military school, where he proved to be a brilliant mathematician, such that he might have had an academic career. But Napoleon was at once romantic, ambitious, and cynical, and the military seemed a better outlet for his talents. The rest of the story is well known- a rapid rise during the Wars of the Revolution, alliances and betrayals, the seizure of power as dictator and then Emperor of the French in 1804, all accompanied by a string of conquests that brought him into total domination of Continental Europe by 1807. The Habsburgs had been forced to dissolve their own, now rival empire in 1806, retaining a rump state called the Empire of Austria, ruled by the former Holy Roman Emperor Francis II. In the wake of all that, in the same year, that same Emperor would send Metternich to Paris with the most important job in Europe, figuring out some way to stop Napoleon.

Metternich was 33 and not yet even at the height of his powers, but he was already known as a formidable political player. He had spent time in some of the most important posts in Europe, including a stint in England, and he knew most of the people that mattered all over. He sized up Napoleon on their first meeting, interestingly, by means of the emperor’s subtle error of protocol- the emperor received Metternich with his court dressed in their finest, but Napoleon wore a hat, despite being indoors. No one born in the purple would have made such a small mistake, and Metternich saw in this minor detail a key feature of Napoleon’s personality that he could exploit- he was a parvenu, and for all his power he retained both a deeply felt resentment against traditional aristocracy and a desperate need to be accepted by it. He was both greater and smaller than the place he occupied. He spoke of being a new Charlemagne, but Metternich’s family could actually trace its ancestry to the Carolingians, and they both knew it.

Metternich was fully aware that Napoleon was every bit as dangerous as he seemed, and realized that if he was to be defeated and Europe set right again, all of the powers of the continent would have to set aside their differences and unite against him. He never failed to respect the emperor’s genuine genius for organization and ruthlessness. Napoleon once told him that he’d spent his whole life in the camps and that the loss of a million men meant nothing to him; Metternich, possessed of a genuine horror of war and destruction, took him at his word. At the same time, though, being close to Napoleon and his inner circle gave him a valuable insight into just how unstable the whole structure really was. The emperor was not the only one nursing insecurities; Napoleon’s siblings, made kings and queens by his hand, his generals- the sons of butchers and innkeepers, and his nouveau nobility- they all had chips on their shoulders and a certain squalid need for validation Metternich could use to his advantage.

So, in addition to high-stakes intrigue involving secretly communicating with counterparts all over the continent, Metternich just started cucking everyone. An inveterate womanizer from a young age, tall and handsome, witty, rich, and powerful, Metternich fascinated women, a list soon to include Napoleon’s sister Caroline. It helped that she was pretty and had the morals of an alley cat, but it helped even more that she was married to Joachim Murat, one of Napoleon’s marshals and the newly-minted King of Naples. She happily fed Metternich information. Napoleon’s propensity to insult and belittle the few holdover aristocrats from the ancien regime meant that the venal Minister of Foreign Affairs, Prince Charles Talleyrand, was soon giving him troop dispositions. Things were looking up for the Austrian Empire.

What do you think, ladies?

Or at least they would have if the leadership hadn’t ignored Metternich and started a war with Napoleon early and on their own. After essentially being held hostage by Napoleon, Metternich was sent home to negotiate an end to the new conflict while Napoleon trained his guns on Vienna. This time Napoleon wanted something other than land; having divorced his coarse and unfaithful Empress Josephine, Napoleon desired a Habsburg trophy bride and the fully realized legitimacy he hoped would come with her. Francis was horrified, but Metternich was a realist, and had the foresight to see that if his plans to undo Napoleon came to naught it would do well to ensure that the next Emperor of the French was of Habsburg blood.

Needless to say, while these delicate, indeed existential negotiations we ongoing, Metternich not only continued his affair with Caroline, but took up with the wife of yet another general, Jean-Andoche Junot, at the same time. Caroline, who had access to her brother’s secret police files, found out that the man she was cheating with was cheating on her, and told Junot (with whom she was also having an affair), who, being an insane syphilitic, attacked his wife with a pair of scissors. Metternich’s wife, who it seems was a good sport about all this, chided him for the spectacle he created, and seems to have been the one who suggested the Princess Marie-Louise as the best choice of wife to Napoleon himself, perhaps impatient at the exhaustion all that diplomacy was causing her husband.

Caroline Murat, nee Bonaparte. After her husband’s execution, Metternich was kind enough to set her up with an estate in Italy. He did the same with Laure Junot, corresponding politely with them both for the rest of their lives, as he did with all of his former mistresses. He was a diplomat in every sense.

So Napoleon got his Habsburg wife, and his dynasty might have lasted a thousand years had it not been for that flaw Metternich saw so clearly. Napoleon browbeat and bullied the ancient houses he now held subordinate, and his rule only made him hated by peoples with a burgeoning sense of nationalism. The wars could never stop, driven as they were less by strategic need and more by Napoleon’s own political and personal insecurities. Invading Russia and turning on his onetime ally, the mercurial Alexander I, Napoleon’s expedition met its famous end in 1812. Metternich was quick to capitalize, using all of his diplomatic pull to create and maintain a coalition of Austria, Prussia, Britain, and Russia, even taking the leading hand in creating its overall strategy of not attacking Napoleon directly, but gradually weakening him and maintaining a united front.

There is a sense in which Napoleon was less an Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar and more of a Pablo Escobar, a latinate middle-class gangster (Metternich summed him up as an “Italian bourgeoise”) who was able to ride the waves generated by social instability to power, but having achieved that, was unable to make the final step to true legitimacy (Escobar ran for a seat in the Columbian Congress but was barred from taking it due to his narcotraficante past). The ruling class he so hated would never give him the recognition he longed for and thus there would never be an end to his war on the existing order of things. All of this culminated in the titanic Battle of Leipzig in 1813, the largest in Europe until WWI, where Napoleon was finally decisively defeated and forced to retreat to France, the armies of the Sixth Coalition in hot pursuit. Napoleon abdicated and was given the island of Elba as his personal domain. Marie-Louise and his young son were brought to Vienna; Napoleon would never see them again.

At this point the work of the generals was (largely) complete and what remained was for the diplomats to rebuild Europe. Metternich was the architect of the Congress of Vienna, a conclave of representatives from the newly re-established monarchies of Europe, that would complete that herculean task. It was he who had been the motive force of all the various coalitions, he who had faced down the Revolution and the warlord it had spawned, and though Austria was by no means the major power on the continent, that meant that he would, through sheer force of will, set the agenda.

That agenda was reactionary. All the old houses would regain what they had had before; the Revolution would be undone. In line with these principles the Congress produced two important agreements. One was the broader and more pragmatic Concert of Europe, which established the principle of balance of power in foreign relations. No political entity would be able to grow so powerful that it could potentially threaten others. This meant that there would be no single Germany, as German nationalists had hoped, as the resulting state would necessarily be too large for the others to abide. New countries were in fact created to even things out, like Belgium. Legitimacy, rather than nationalism, would be the new order as it had been the old order. The second was the Holy Alliance, made up of Austria, Prussia, and Russia, each bound to snuff out any manifestation of revolutionary sentiment, or even liberalism, in their territories.

Nationalism, liberalism, socialism- all the -isms, really, would be the enemy Metternich would combat for the remainder of his long life. Much is made by critics of his use of spies and secret police, but his repression pales in comparison to that employed wherever the forces he opposed gained power. Metternich was also far more pragmatic and realistic that his contemporary Joseph de Maistre (interestingly they never seem to have met, though both were diplomats) and did urge reforms (unsuccessfully) such that the later Otto von Bismarck was able to enact to steal the causes of liberals out from under them. In addition to the burgeoning nationalism brought about in reaction to Napoleon’s conquests (the Congress kept going during Napoleon’s return and subsequent second and final defeat and exile), there were also the Industrial Revolution and the bourgeois-tinged monarchy of England that loomed as threats. Metternich fought hard against the changes these forces threatened, but was finally toppled from power in the revolutionary year of 1848, and went into exile in the very England that had opposed him. Recalled home, he served in a basically advisory role to the Habsburg crown until his death in 1859.

Our modern governments’ main task is producing both.

Was he successful as a whole? I would argue that he was, and spectacularly so, at least for his time. The Concert system gave Europe its longest and most productive era of peace in its history, a peace brought about not by democratic consensus, but by aristocrats and monarchs caring for their patrimony. The forces he opposed, nationalism, liberalism, socialism, and the power of bourgeois finance and capitalism would in the end triumph and lead to two disastrous World Wars, colonization by American military and financial power, an inundation of Third-World immigration, crime, and loss of the very identity all that nationalism was supposed to ensure, and rule by managers who see their charges less as children to be loved as cattle to be farmed.

Metternich was a gifted man who spent his entire privileged life in service to others, always subjecting his own will to the greater good of the house he served and the people over whom he had power. Against the Nietzschean Napoleon, who conquered for the sake of conquest, Metternich understood that his station in life was a gift from God and that his worldly treasures and talents were not his own to be used for his own ends but for the benefit of others. Napoleon and the Revolution brought chaos and destruction; Metternich brought about RETVRN. He was a true aristocrat of the soul, and we will never arise from our current dark age until his like is seen again.

My entire piece was about how brilliant and essential Metternich was; at no point did I shortchange him as a “well-bred pimp.”

I’m not sure what your second paragraph means. Metternich was opposed to the Revolution and Napoleon from the start and Austria was the motive force on the continent behind the various coalitions.

Napoleon was a creature of the Directory, was sponsored by them, and betrayed them. I explained the Escobar analogy.

I point out in the essay how much Metternich respected Napoleon’s talents, drive, and genius. Napoleon’s aristocracy was just his aping of the actual thing, his crew of gangsters being handed titles for their loyalty to his regime. At no point did the French Empire have balanced budgets; it was a predatory enterprise that funded itself through plunder and kept its war machine going through forced levies of troops from conquered populations. The idea that women did not play an important role in the culture, diplomacy, and intrigues of the day is without support in the literature, primary or secondary.

The Bourbons are still the reigning monarchs in Spain. I make the same point about liberalism etc. in my essay.

When the warlord does come, it will be terrible, more so because their is no Metternich to oppose him. Such a figure, a true aristocrat of the spirit and not a bloody gangster, will have to emerge from the same mists of history as a true king, and may God speed the day.

What I'm getting out of this is that Metternich deserves to have a bunch of those neon RETVRN memes and maybe a Little Dark Edge edit. For real though, good write up for a criminally underrated figure of the Napoleonic age. Even though the eponymous French chud himself is, obviously, pretty important to the time, I think you only appreciate and understand his story and time period itself if you also understand most of the other players, but they all get overlooked because... they aren't flashy enough, I guess.

All sigma beta incel whatever jokes aside, the movie seems like it's going to just be fodder for pop history TEN THINGS YOU DIDN'T KNOW ABOUT type things to pick apart for the next fifty years. I don't think I've ever seen a movie's hype deflate as quick or as hard as this one. It's so over for Napofags.