Like most of you, I saw the now infamously viral Harris campaign video where a group of real men emerged briefly from their closets to inform America that real men deadlift, eat carb(uretor)s, and vote straight (no pun intended) longhouse. Here it is in case you missed it.

The more you declare you’re not afraid of women, the more true it makes it. Also, the original seems to have vanished from YouTube . . .

Filmed somewhere in the uncanny valley and presumably directed by

, the video was obviously roundly mocked by every male not regularly consuming three meals a day of Cinnamon Toast Crunch and soy milk. But if I might venture into controversial territory here, I would say that the short ad evoked more than just ridicule. Laughter is, in the end, a type of mild fear reaction, and for my part at least, I found the video to be subconsciously unsettling in a subtle but pervasive way. It reminded me of something, something much better that conveyed the same sense of unease in a more powerful and visceral manner.What else?

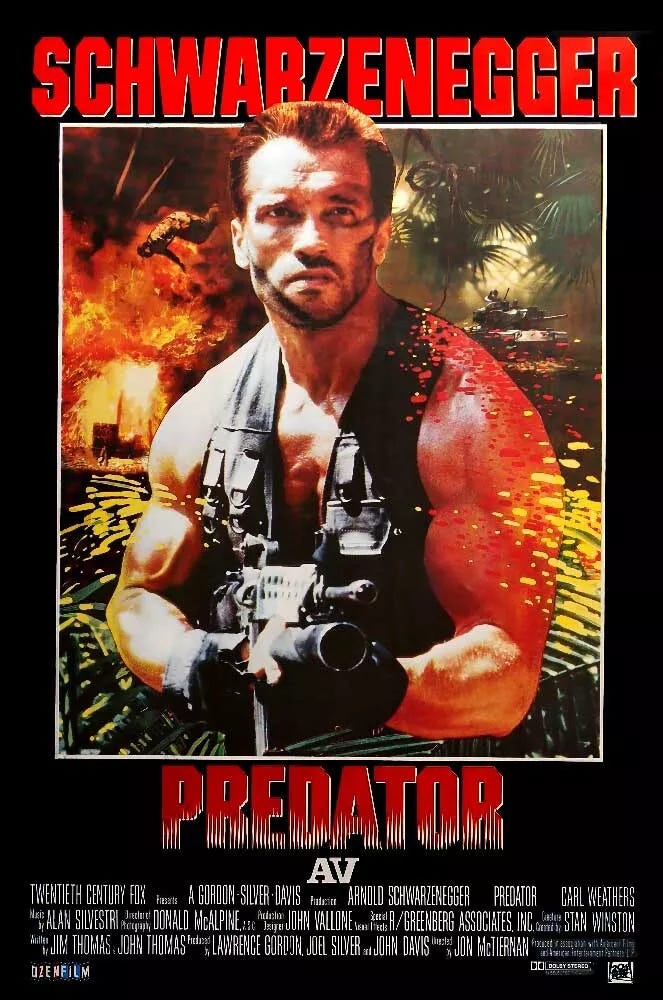

Predator (1987) is not what you remember, or at least, it’s not just what you remember. Ostensibly a clever sci-fi/action/horror film, it’s not a classic solely due to the cast of 80s greats, explosions, and innovative plot. There’s a subtext to Predator that makes it truly frightening in a way that none of its sequels, crossovers, and reboots ever really captured. It speaks to a deeply primal part of the male mind because in the end, it’s not really about a monster killing people. The Predator isn’t really a scary alien; he’s an allegorical parallel for those forces in modern life that strip men of their manhood, the most important of which being that managerial neoliberalism that robs men of agency, energy, and any scope for courageous action.

The movie opens with a shot of a spacecraft, of obviously alien origin, heading towards Earth. It will be a while before the meaning of this is made clear, but it introduces from the outset that there is something foreign to the human experience at work. The audience is then introduced to the main cast, flying in on military helicopters accompanied by some of the greatest movie scoring of all time. I have no doubt you can hear it in your head as you read this (dadadadaDAHda, dadadadaDAHda, duh duh duh . . . ).

The only way it could possibly be improved would be for it to be performed by the Guitar Army from Idiocracy.

To an audience in 1987, the imagery of a Huey flying in over a jungle into some kind of forward operating base would have evoked two things; the relatively recent debacle in Vietnam and the contemporary and controversial American presence in Central America. In both cases, the US military was sent to face a shadowy enemy, the human elements of which were mere avatars for ideological struggles between rival systems of managerial control. But the men exiting the choppers are clearly not the fungible regulars or hapless draftees of the Vietnam era. Dressed in civilian clothes and carrying themselves with swaggering distain, they are quite obviously less soldiers than warriors.

This will be a running theme of the movie, right down to the ambiguity about who they actually are. They have- or had- military rank and are addressed as such by the officers who summoned them. But it’s also made clear that they are not under normal command, as their leader, Dutch, played (iconically and memeably) by Arnold Schwarzenegger, explains that he “passed” on a previous job due to it being an assassination mission, while his men are a rescue team. As we’ll soon see, both their physiques and equipment are wildly impractical for men operating under normal military protocols, but exactly the sort of presence a buffed-up modern Viking might affect. Are they Delta Force? Mercenaries? It’s difficult to tell, but one thing made clear in that brief exchange is that Dutch and his men live by a code of honor in which warfare is a noble profession but certain actions are beyond the pale.

The basic plot of the movie is outlined in this scene; it is explained to Dutch that his unit’s mission is to rescue a cabinet minister and his aide being held hostage deep in guerilla-controlled territory in the unnamed Central American country just over the border from the base (possibly the fictional Val Verde beloved of 80s writers). When Dutch inquires why his men have been asked to perform this operation rather than a more conventional unit, he gets the answer from a familiar voice, Dillon (Carl Weathers). Evidently old and welcome friends, Dutch and Dillon share the most unironically macho hand holding and deep eye contact possible as they test each other’s strength since they last met.

There’s an important subtext to all of this that’s easy to miss on the first viewing. Dillon’s past affiliations notwithstanding, he now works for the CIA, at the very center of the managerial state. Dutch explicitly connects Dillon’s new role to a loss of masculinity, manifesting as physical weakness with the implication of a loss of solid morality as well. On that point, despite knowing Dutch well, Dillon expresses incredulity regarding the former’s professed reluctance to engage in targeted killings, and there is clearly something that both he and the general in charge know that they are not saying. Dutch is skeptical of the mission and is chagrined to discover that Dillon will be accompanying his team despite Dutch’s standing policy against such. The general’s reply that “I’m afraid we all have our orders” is another tacit admission that Dutch is dealing not with warriors but functionaries, men content to fill a role in a some grand design, the scope of which they are not aware of and which they’ve accepted will demand of them moral compromises of a type Dutch disdains. Dillon’s presence on the team amounts to a type of emasculating spiritual pollution, the full implications of which will only be made clear later.

The team sets off, and another excellent scene follows in which the remaining team members are introduced. Among other great reasons to watch Predator is that it serves as a master class in efficient characterization. In just a few minutes, and with virtually no exposition, the audience gets a clear idea of who these men are and their bonds with each other. They are almost parodically manly, though the real chemistry between the actors keeps it surprisingly grounded- listening to classic rock music, reading comic books, telling dirty jokes, and for the bombastic redneck Blaine (Jesse Ventura), chewing the tobacco that renders him a “sexual tyrannosaurus" compared to the “slack-jawed faggots” who refuse to join him. Having associated his cheek of Grizzly with his manhood, Blaine then spits out the juice onto Dillon’s boots, an act of territory marking and sexual aggression. The most ostentatiously macho member of the tribe, Blaine seems viscerally sensitive to the threat Dillon poses to their unit cohesion. Mac (Bill Dukes), Blaine’s closest friend in the group, will also later (and more directly) threaten Dillon along those lines.

The group lands and makes its way to the site of the cabinet minister’s helicopter crash where the trail they expect to follow should begin. Predator is in many ways a Cthuluesque film, in which humans in an ostensibly normal universe are gradually made aware of cosmic horrors beyond their understanding, and it is here that that element is first introduced. The way it’s done is worth noting. The helicopter didn’t simply crash, it was shot down by a heat-seeking missile- thought to be beyond the capabilities of the local guerillas- and the cabinet minister and his aide were then captured. But the unit’s tracker, Billy (Sonny Landham) discovers that that group was followed by six men in US Army boots, which Dillon claims to know nothing about. Ramirez (Richard Chaves) then stumbles onto a horrifying scene, the six men, skinned and gutted and hung from vines, their entrails spilled out onto the jungle floor. Billy finds evidence of a firefight, but inexplicably one-sided, with the six men- who turn out to be Green Berets, one of whom Dutch knew personally, firing in all directions against a foe that left no tracks. Meting out such a gruesome death is uncharacteristic of the guerillas, who also would not have left behind the soldiers’ valuable equipment.

The evidence at the scene makes no sense to the unit, and though it will be clear to the audience in time what is going on, it is important that the movie here layers two mysteries together. The characters are as yet unaware that the government is lying about the circumstances of the crash and that the titular Predator is the one who killed the Green Berets. The dead men are victims of both, put in place by one and slaughtered by the other. Two forces, both distant and alien, work in narrative tandem to snuff out life in this jungle warzone.

The group makes it to the rebel base, and seeing one of the hostages being executed, decide to attack. As this is an 80s action movie, the prospect that there might be other hostages still present and alive is ignored in favor of immediately launching a truck-bomb at the mess tent and just shooting and blowing up everyone after unlocking the infinite ammo mod. It’s a great scene, making liberal use of the ‘giant-fireball-human-flipping’ grenades that movies love so much.

What actual grenades do isn’t quite as visually compelling, but definitely effective.

This is the peak of the action movie aspect of the film, standard 80s stuff- buff Americans shredding foreigners with lead while dropping one-liners. The team are clearly meant for this sort of thing, born warriors in their element. But this scene is important for a lot of other reasons as well. There are several shifts that happen here that color the rest of the film and set the stage for the true horror to come.

First, near the end of the fight, Dutch is stalked by one of the guerrillas, whom he knocks out with a butt-stroke from his rifle. He’s chagrined to discover it’s a woman. Why she walked towards him with her pistol extended instead of simply shooting him while his back was turned is unclear; perhaps, being a lady communist, her instinct was to nag him to death instead. This is Anna, (Elpida Carillo), who, at Dillon’s insistence, will be joining the crew as a prisoner. It’s also revealed at this point that the whole operation was a lie, that Dutch and his men were meant to destroy this guerilla base, and that Dillon knew about the Green Berets. Though he feels some measure of guilt for sending those soldiers to their still mysterious deaths, he coldly informs Dutch that he and his men are expendable assets, and that his lies to get them there were simply part of his job. Dillon also curtly notes that he is in still in charge in any case.

With the addition of a woman to their group (the only woman in the entire film) comes the major narrative shift for which her presence serves as a marker. The movie switches from being a military-style action movie and transitions into sci-fi/horror. The team in turn go from being subjects whose agency drives to action to objects forced to react to increasingly bizarre events instigated by a new force- active manhood replaced by feminine passivity. It’s a subtle shift but very real, and the rest of the film, up to the conclusion, sees this new dynamic play out.

The Predator has at last noticed them. That he is the driver of events from this point is represented by his being the only character shown consistently in first-person view, his iconic infrared vision reducing the individual characteristics of the team to blobs of heatwaves. The parallels suggested by the initial mystery manifest themselves here once more. Like the managerial state that sent the unit to the jungle, it’s quickly revealed that the Predator views them, quite literally, as nothing more than meat and energy that he can exploit for his own ends.

First to die is Hawkins (Shane Black), sent to chase down the escaping Anna. The Predator slashes him to death with a blade and makes off with his body before anyone can see him. The characters are as yet unaware of the full implications of what is happening, and Dillon attributes his death to the guerillas, who the team realize are massing to counterattack before the latter can reach the border. Dutch points out that Anna didn’t run away and that the guerillas would have no reason to take Hawkins’ body. For her part, Anna keeps repeating in Spanish that the jungle came alive and took him. Nothing about the situation makes sense, and on top of the mysterious death of their friend, the strangeness of it all begins to unnerve the team.

Blaine is killed, shot through the back by an energy blast from what will come to be known as one of the Predator’s signature weapons. Mac catches a glimpse of the strange being, cloaked in a light-bending camouflage energy field. Beyond the practical value of such equipment, narratively speaking the cloak represents the formless and invisible nature of the threat they face. Parallel to this the team learns by radio that they will not be evacuated, as having destroyed the guerilla base as intended, the Army won’t be taking any risks to get them out. Dillon learns that he is just as expendable as the rest of them. There is no face to the being that hunts them and no face to the managerial system content to leave them alone to confront it.

As they trek through the bush toward the border it begins to dawn on them that they are up against something that is unlike any threat they’ve ever known. They begin to break down mentally. It’s not entirely one-sided. When the Predator is wounded in a firefight while attacking them, the team sees that what stalks them bleeds fluorescent green (the practical effect was created by blending KY Jelly and glowstick fluid). Dutch alone takes heart from this, noting that whatever it is “if it bleeds, we can kill it.” However, their efforts to do so come to nothing. Billy, previously calm and collected throughout, starkly announces that he’s afraid, and when challenged by Ramirez that Billy fears no man, Billy just as passively declares that what they face is no man, and that they’re all going to die. Mac collapses into full hysteria, chasing the creature alone into the jungle. Dillon, in an act of redemption, pursues him despite knowing it means his own death. Both are killed. The audience sees the Predator more clearly here, and though the men he hunts are massive, he towers over them. More importantly is the narrative counterpoint; the same men who earlier casually took out an entire battalion’s worth of armed insurgents are now mentally and physically helpless to defend themselves against a threat they don’t yet fully comprehend.

They come to understand at last that they are being hunted, that their mission has intersected a strange point between an omnipresent managerial military colossus unwilling and unable to help them make it ten miles out of the country and an alien force representing the most atavistic form of death-dealing possible. In between, their sense of themselves as warriors and men is ruthlessly deconstructed as they find themselves reduced at the same to both fungible assets and literal prey. Interestingly, it’s Anna who finally confides that her people have some idea of what they’re facing. Living in the jungle and in harsher conditions that her First World American captors, she is situated as an outsider in the sense of being both female and foreign, able to offer some perspective on their situation. As the final few run from the oncoming threat, Billy, in a Nietzschean-existential moment, refuses to run further and faces death on his own terms, knife in hand, refusing to surrender to his fear or to what anyone else would make of him. We later see the Predator stripping his body like a trophy buck, ripping out his spine and carefully treating his skull for evident display.

The audience and Dutch realize together that the Predator, for all its ruthlessness as a hunter, has a kind of sportsman’s code whereby he refuses to attack the defenseless. It comes too late to save Ramirez, but knowing this, Dutch makes a distraction of himself in order to allow Anna to flee. His self-sacrifice earns him a plunge into a river and the accidental discovery that the cold alluvial mud masks his heat signature such that the Predator cannot see him. In a sense, his adherence to his own warrior code in the face of cosmic horror results in a kind of rebirth, almost a baptism into a more primal mode of existence. He enters the water a modern soldier and leaves a painted warrior. No longer does he have a team with high-tech gear; a subsequent montage shows Dutch alone, half-naked, setting traps and armed with a primitive bow.

This is interesting because, from a narrative standpoint, the logical thing for Dutch to do at this point would be to make his escape. He knows how to make himself invisible to the Predator and that so long as he presents no challenge the Predator would not bother with him in any case. But there’s something deeper at work. Both the Predator and the mission have challenged and upset his self-conception as a man. His identity as a warrior has been shaken by those parallel forces that have thus far has demonstrated their power over him. The fight with the Predator is not about physical survival, but rather the psychological preservation of his masculinity, and by extension, that of his fallen mannerbund. To redeem their warrior manhood, and his own, he must win this fight.

The battle is initially a hard-fought back and forth through the jungle. Dutch and the Predator initially fight with ranged weapons, but draw ever closer as they each attempt to kill the other. Despite Dutch wounding the Predator, or perhaps because of it, the Predator at last elects to face him hand-to-hand. The fight that follows is remembered as an epic action scene, but here too there are unsettling elements one might miss from a casual viewing.

The combat opens with the Predator unmasking and revealing his face for the first time. While his physique is that of a physically imposing humanoid, his visage is alien yet evocative. His brow ridge and dreadlock ‘hair’ give an aura of primitivism, but the most memorable trait is the mandibles, the verticality of which convey the impression of a strange vagina dentata. A Freudian would have a field day with all of the phallic-destruction imagery already present in the film (Dillon’s severed arm; Billy’s wrenched spine…) but that mouth strikes nerves even in the most obtuse normie. It goes without saying that the Stan Winston practical effects in the movie are amazing and still hold up today.

The fight is less combat between champions than the Predator slapping Dutch around like dinner wasn’t ready when he came home from the bar. In fairness, this was at least partially due to the actor in the Predator suit not actually being able to see and his moves having to be executed blind from a practiced sequence, thus limiting the range of strikes. But visually it furthers the impression of the unmanning being executed upon Dutch, reduced from blowing up commies to domestic violence victim.

There’s a telling moment in the fight that illustrates this perfectly. Knocked to the ground, Dutch crawls away from the Predator to a trap he’s pre-stationed. The Predator calmly approaches behind, extending his two (paging Dr. Freud) arm blades in anticipation of his kill. In horror movies there’s a trope called the Dramatic Slip, where the (almost always) female victim of a slasher villain inexplicably trips while running from him, but rather than get up and keep running, she always equally inexplicably just desperately crawls away while the psycho killer casually and menacingly approaches, implement of death in hand. If you replaced the Predator and his arm blades with Freddy and his glove or Jason and his machete you’d have the exact same visual cues that would resonate with an 80s audience, provided of course that the role of helpless cheerleader was filled by Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Here’s a supercut.

But despite sensing the trap the Predator is oblivious to its counterweight component hanging above, and Dutch is able to drop it on the alien hunter, crushing it beneath a log. Leaping up the execute the coup de gras, Dutch is instead transfixed in curiosity. He asks the creature, “what the hell are you?” The Predator, able to mimic human speech as a hunting lure, responds by repeating the same question back to Dutch. What is he indeed? He bested the Predator, but only through a trick; he survived, but, having undergone this inhuman ordeal, will he ever be what he once was again?

The final sequence is where the parallels finally cross and the full cosmic horror manifests itself. The mortally wounded Predator activates a self-destruct mechanism. Sensing this, Dutch flees to the sound of the Predator’s maniacal imitation of his dead comrade Billy’s laughter. The explosion is that of an atomic bomb, which Dutch manages to outrun (just go with it) and finally make it to the helicopter, flying away, the audience sees the mushroom cloud in the distance.

Ernst Junger wrote of the atom bomb as the culmination of nihilistic modern warfare, a super weapon that eliminates human significance from martial struggle, obviating the very possibility of courage. The premise of managerial rule is technocratic omnicompetence; whether liberal West or communist East the elites ruled according to the same premises and the bomb, under their control, was the ultimate backstop to their power. But here at last they’re revealed as just as powerless as Dutch. An alien force, outside of their control, has brought along the most powerful weapon humans have and uses it to clean up after a failed hunting trip. Not only nihilistic but absurd- if the point was to cover up your alien presence, why do so in a way that sets off radiation detectors globally, and if the Predator didn’t care if the humans knew it was there, why blow up in the first place? The pointless atomic destruction in that contested Third World space between the superpowers symbolizes at last the impossibility of manhood in the modern age.

Bleak stuff ostensively, but there is a hint of hope. It would be too much to say that Predator prophesied the ultimate unsustainably of the managerial state under the weight of its own contradictions, but in the years since 1987 the Soviet Union, the less capable manifestation of Enlightenment scientific progressivism has collapsed, and it’s not to much to hope that liberalism follows suit. Men like Elon Musk dream of technology harnessed not to managerial control but in fulfillment of human meaning. Such wonders that might come will support, indeed demand manliness, perhaps not the sort that blows things up, but definitely the same sort of moral courage at the heart of the film, the bravery that binds men together for noble ends. And if Predator can inspire that, then I would call it a happy ending.

For fun, try watching this other famous scene with a monster portrayed by an actor unable to see through the mask. Ignore the fact that they both move like they’re fighting underwater and that the alien sounds like he has a two-pack-a-day Lucky Strike habit and notice the similarities, right down to the strike with a tree branch.

I must admit I didn't expect a Predator deep-dive at the Library, but I'm very happy you wrote it. You've got a talent for finding metaphor in the most unusual places. One thing that came to mind is that to the managerial state, anything outside the state is alien, to be killed or brought under control. Illegible things are terrifying to the managerial technocracy. Rednecks surviving a hurricane in the deep south are completely inscrutable, invisible, and thus, dangerous.

To the longhouse schoolmarms we're the Predator.

Great movie, and a great essay. Thanks!

Very interesting review, and I suspect you're on to something. A lot of manly action movies of that period that were broadly dismissed as brainless jingoism actually have some pretty sophisticated themes and an anti-establishmentarian streak reflecting the technocratic failures of Vietnam and the Carter years. Appreciate the "Arena" clip also, quite possibly my favorite episode of the original series!