[As Fathers’ Day approaches, and with the anniversary of D-Day just past, I thought I might combine something of both themes into a single post, though with more of the former than the latter. Our society too often denigrates fathers, which is of a piece with the general rejection of God, and even those charged with encouraging reverence for the latter commonly take the occasion of Fathers’ Day to disparage the latter. Enough of that. Fatherhood is a high calling, and great examples of fatherhood- and leadership more generally- should be the prime focus on that one day, if not commonly. As such, I offer the following on Theodore Roosevelt and his family. He and they were by no means perfect, but one would be hard pressed to find a notable public man who tried harder.]

Theodore Roosevelt, like most great men, was a mix of positive and negative qualities, all bound up with the whirlwind energy of his ambitions. Remembered today primarily as the youngest man ever to become president, though not the youngest man elected president (look it up for trivia night), to think of him solely this way is an impoverished take on his life. He was, over the course of his relatively short time on earth, a groundbreaking historian, a gifted naturalist, a big game hunter on four continents, a legislator, a cowboy, assistant secretary of the navy, a martial artist, a lawman, a military officer, a governor, a civil service reformer, an explorer, a journalist, and of course, a statesman. I have no doubt commenters will name some things I missed. He was also a chauvinist and a warmonger, a man for whom violent action was an end in its own right, possessed of the notion that white imperialism was a progressive force that would uplift benighted brown people the world over. But perhaps the most important aspect of his life, the point at which all of his traits came together, and the most personally rewarding to him, was his role as a father.

Roosevelt came from an (in American terms) ancient family that was long accustomed to money and high social status in his native New York. His father, Theodore Roosevelt Sr., was a beloved civic benefactor and a genuinely kind man who loved his children dearly. Theodore was the second of four and the oldest son (his younger brother Elliot would father Eleanor, who would marry a fifth cousin from another branch of the family). A sickly child, asthmatic and scrawny, Roosevelt was the butt of bullying, for which his father prescribed a strenuous life, hiring prizefighters and muscle men to teach his son to embrace his physicality, which would prove a lifelong pursuit. Despite terrible eyesight, he took to the life of a sportsman, hunting the American wilderness, which as president he took such pains to preserve.

TR’s constant need to prove himself was not only rooted in his father’s positive exhortations, but in another -to the son- shameful episode in his father’s life. Roosevelt Sr., like many men of his social class, paid a substitute to take his place during the Civil War conscription. This was on one level a perfectly rational choice; the Lincoln government needed the $300 more than the front-line service of a businessman in his 30s with no military experience, and Roosevelt Sr. had an important role administering several charities for the Union cause. There was also the fact that Mrs. Roosevelt was the former Martha Stewart Bulloch of Roswell, Georgia, and openly supported the Confederacy, with her three brothers serving the Southern cause in various capacities (TR remembered helping his mother make care packages for Confederate soldiers whenever his father was away). As such, it made sense for him to stay out of the conflict for all sorts of reasons, but for his son, burning with a profound compulsion to cultivate and demonstrate his own masculinity at his father’s urging, such rationalizations could only cause a psychic wound, the pain of which urged the young TR forward like the spur in the flank of a warhorse.

He would never know his father as a man; while TR was away at Harvard his father died from an illness he’d concealed from the family until it was obviously mortal. TR raced home but arrived hours too late to his father’s deathbed. Some have argued that TR’s characteristic whirlwind energy and passion for action represented a type of arrested development that manifested itself in a lifelong need to prove himself to as an adult to a man he would never relate to as one. True or not, I think the premise of such thinking is that a mindset like that is something unhealthy, and though the notion now is common, I think there’s a good bit positive about feeling a need to demonstrate your worth at all times, especially in the eyes of worthy people, and most particularly in the estimation of a worthy father. Looking up some dates on Wikipedia, I found this quote from a letter from TR about his father that perfectly epitomizes this idea:

I was fortunate enough in having a father whom I have always been able to regard as an ideal man. It sounds a little like cant to say what I am going to say, but he did combine the strength and courage and will and energy of the strongest man with the tenderness, cleanness, and purity of a woman. I was a sickly and timid boy. He not only took great and untiring care of me—some of my earliest remembrances are of nights when he would walk up and down with me for an hour at a time in his arms when I was a wretched mite suffering acutely with asthma—but he also most wisely refused to coddle me, and made me feel that I must force myself to hold my own with other boys and prepare to do the rough work of the world. I cannot say that he ever put it into words, but he certainly gave me the feeling that I was always to be both decent and manly, and that if I were manly nobody would laugh at my being decent. In all my childhood he never laid hand on me but once, but I always knew perfectly well that in case it became necessary he would not have the slightest hesitancy in doing so again, and alike from my love and respect, and in a certain sense, my fear of him, I would have hated and dreaded beyond measure to have him know that I had been guilty of a lie, or of cruelty, or of bullying, or of uncleanness or cowardice. Gradually I grew to have the feeling on my account, and not merely on his.

TR would marry twice. His first marriage, to Alice Lee, produced a daughter, also named Alice, but the delivery sadly resulted in her mother’s death. This was in fact the second tragedy of the day; in the same house, earlier that morning, TR’s widowed mother had passed away from typhoid fever. It was Valentine’s Day, 1884. Devastated, TR left his newborn daughter with his older sister Bamie and headed west to the Dakota Territory, looking to start life anew, but after a few years, his cattle ranch went under during the “Big Die Up” series of blizzard-filled winters from 1886-1887, and he returned to New York. There he reacquainted himself with a friend of his younger sister Corinne, Edith Carow, and he married her shortly after. He resumed his political career and started family life once more.

Roosevelt strongly believed in big families for a number of reasons. Practically speaking he was concerned about what he saw as a dearth of white people in the world, and believed that nothing would threaten the progressive ascendency of white supremacy like modern elites going the way of the childless, decadent Romans. TR famously believed that “all the great masterful races have been fighting races,” but alongside that they were also reproducing races- in his essentially Darwinian worldview battles were fought as much with babies as with bullets. That said, TR also genuinely loved children and wanted as many of them as he could. Thus, he was overjoyed when Theodore “Ted” Roosevelt III was born in 1887, followed by Kermit in 1889, a second and final daughter, Ethel, in 1891, Archibald (Archie) in 1894, and Quentin, the last, in 1897.

Roosevelt was a supremely ambitious man who fetishized strength and action and wanted his country to do the same. He was at once a passionate believer in what he saw as progress and liberal democracy, but at the same time recognized that he belonged to a privileged aristocracy which he firmly held should run not only the US, but the world. He squared this circle in his own mind by demanding of himself excellence in every area that could be expected from a man of the ruling class, and taught his children, boys and girls, likewise. Saying you were better than others because of birth and breeding meant nothing; being better than others by proving yourself meant everything. It should be emphasized that this vision of constant striving for domination was leavened by Roosevelt’s Dutch Reformed faith and was, for him, primarily a moral enterprise- what the white rulers of earth would offer others was a something uplifting, a more hopeful existence brought into being by the hard work and sacrifices of men like him. It was not for nothing that Kipling and Baden-Powell were family friends.

Thus, the Roosevelt children grew up in an environment where they experienced great love and great expectations. Others, particularly in their own social class, considered them a bit rowdy and unmanageable; for their part, they were a close-knit bunch who could be a bit hard on outsiders. Cousin Franklin, for example, was athletic enough for most people, and no dullard, but behind his back the Roosevelt boys called him ‘feather-duster’ and ‘Miss Nancy.’ They hunted and fished and camped in the wilderness, with their father telling ghost stories and leading every hike with his irrepressible energy. Sports were a constant- Roosevelt was a huge believer in the benefits of football in inculcating the proper spirit of militarism in coddled modern boys. Roosevelt wrote about the subject in 1900 in an article for St. Nicolas magazine called “The American Boy.”

The great growth in the love of athletic sports, for instance, while fraught with danger if it becomes one-sided and unhealthy, has beyond all question had an excellent effect in increased manliness. Forty or fifty years ago the writer on American morals was sure to deplore the effeminacy and luxury of young Americans who were born of rich parents. The boy who was well off then, especially in the big Eastern cities, lived too luxuriously, took to billiards as his chief innocent recreation, and felt small shame in his inability to take part in rough pastimes and field-sports. Nowadays, whatever other faults the son of rich parents may tend to develop, he is at least forced by the opinion of all his associates of his own age to bear himself well in manly exercises and to develop his body—and therefore, to a certain extent, his character—in the rough sports which call for pluck, endurance, and physical address.

But Roosevelt was hardly anyone’s idea of a jock. Possessed of an eidetic memory and a first-rate intellect, he authored an astonishing forty-six books throughout his extremely busy life, on a range of subjects that included natural science and ecology, travelogue, history and historiography, political science, hunting, womanhood (I really need to find that one), exploration, and even philosophy (The Strenuous Life, from a speech he delivered, very much falls into that category). That sort of output demanded huge input, and it was nothing for TR to read serious books as the rate of one per day even in the midst of his other activities. If he wasn’t the most well-read political figure of his day I don’t know who would be. His children absorbed this commitment to learning and studied their father’s grown-up books, fearing anything like a poor showing in school.

But perhaps the most unique feature of their childhood was the fact that they grew up with the glare of the world upon them. Their father’s (authentic and energetically self-advertised) heroism in the Spanish-American War made him a celebrity, and the Republican Party of his day knew exactly what to do with a young zealot passionately committed to reforming political and business corruption- they packed him off as the inoffensive William McKinley’s vice-president, the then-traditional office where political careers went to die. Ironically enough, it would be McKinley’s career that would come to a sad end, with Leon Czolgosz doing his part for the popularity of anarchism and foreigners by shooting the president while shaking his hand. Roosevelt was now president without owing any favors to his party’s power brokers and had a free hand to impose his considerable will on the country, with his children along for the ride.

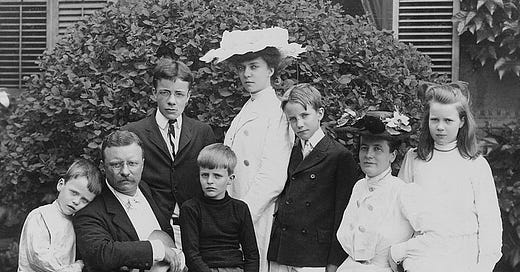

The above photo captures a lost world. The image is of an alien people, with a demeanor hard to fathom in our far different age. The picture is from Roosevelt’s first term in the White House, but was taken at the family home of Sagamore Hill on Long Island. TR, then 44, is obvious on the left, as is Edith, 41, matronly at a time when that was still something women aspired to be. Alice, 19, stands in the top middle. Ted, to her right, looking like a bank president, is 16. On Alice’s left is Kermit, 14. Ethel- a stout girl her loving-but-not-always-sensitive father nicknamed ‘Elephant Johnny’- is 12. Archie, sitting on his father’s knee, is 9. The boy with his head resting on his father’s shoulder is Quentin, 6. He has thirteen years to live.

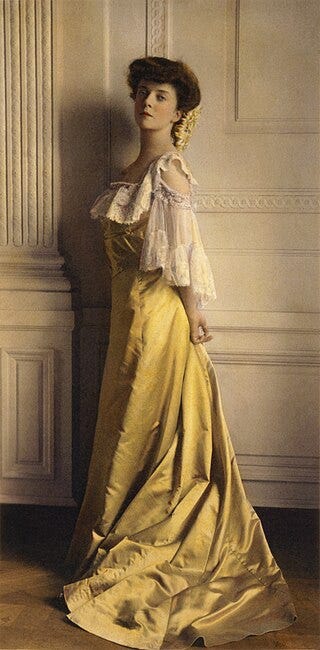

All of the Roosevelt children merit essays of their own, but Alice could really only be done justice by a book. Unflatteringly but fairly accurately nicknamed ‘Princess Alice’ by the press of the day, it is easy to see why. There are no pictures of her from any point in her long life where she does not appear haughty. Her childhood was the hardest of the Roosevelt children and of all of them her relationship with her father was the most strained. Theodore Roosevelt never mentioned her mother, even to the point of excluding his first marriage from his memoirs, and called Alice ‘Baby Lee’ rather than the name that reminded him of his first wife. She did not get along with her stepmother and for her part Edith could be cold to the girl who was living proof she was TR’s second choice, once remarking to Alice that had her mother lived she would have bored Theodore to death (an older Alice came to appreciate Edith more and even agreed with that assessment).

She inherited her father’s need for attention and his willfulness, and was like him in ways that certainly made him uncomfortable. Alice was by far the wittiest of the lot and the most insightful, always acid-tongued but seldom wrong in her characterizations of others. Of her father she remarked he “always wanted to be the corpse at every funeral, the bride at every wedding and the baby at every christening.” She shared the same longing, but whereas her father was drawn to public service, Alice preferred to go her own way in all things, living the life of a celebrity at the dawn of the age of mass media. She smoked and drank and gambled, refusing to attending the tony but conservative girls’ school her parents wanted for her. She married exactly the wrong man for exactly the wrong reasons, a congressman fourteen years her senior who would shortly become Speaker of the House, and they promptly commenced cheating on each other such that her only child was sired by one of his political rivals.

And yet, she was not without her virtues. Alice spent her entire life in Washington and knew everyone who mattered, the sort of character Dominick Dunne would have invented if she hadn’t actually lived. She could make or break political careers- her characterization of Thomas Dewey as resembling the plastic groom on wedding cakes was widely held to have helped tank his campaign as much as the Low-Energy Jeb tag from Trump did to the Bush dynasty’s aspirations. Asked about cousin Franklin, she stated she would prefer to vote for Hitler. She was a great friend and a powerful enemy, respected by the likes of brilliant men like RFK and Nixon, who both greatly esteemed her advice. She was a journalist and active in numerous charitable causes, pursuing every activity with characteristic Roosevelt energy, even in her old age after a double-mastectomy following breast cancer, calling herself “Washington’s only topless octogenarian” in order to raise awareness. Those close to her remarked on her great personal warmth and solicitude. Though she was the oldest of TR’s brood she outlived them all, finally slowing down long enough for death to catch her in 1980, at the age of 96.

Of the others it would perhaps be most useful to examine them from youngest to oldest. Quentin was the most intellectually gifted of TR’s children, a promising scholar from a young age who was additionally a gifted poet and writer of fiction. Like all the Roosevelt boys he was both tough and fearless, and had fully absorbed the fighting ethos of his father. When WWI began he was at Harvard, but, along with his brothers, commenced military training on his own initiative in anticipation of the US becoming involved, for which TR was a passionate advocate. When the US joined the Allies, Quentin used his rich people connections to get into action quickly, and demonstrating both his courage and his forward-thinking nature entered the fledgling Army Air Corps.

Flying those early warplanes was a hazard in itself, even absent combat. Roosevelt crashed more than once in training, which may also have had something to do with the bad eyesight he concealed to get his billet. He managed to down a German plane in combat, and bad vision or not, his comrades remarked on his reckless bravery and said often that he would either achieve greatness or die. He might have been the American Junger. But it was not to be. On July 14th, 1918, four months before the end of the war, and after only nine days in action, Quentin was shot down behind enemy lines. He was probably dead before he hit the ground. Though buried respectfully by the German army, civilian authorities made a postcard out of a photo of his crashed plane and mangled corpse. They intended it as propaganda, but it backfired among the German ranks, as the soldiers understood that the sons of the former US president were fighting at the front while the sons of the Kaiser and his general staff had cushy appointments in pleasant places. One of those postcards was actually mailed to the Roosevelt home in order to upset him. TR chose to display it proudly, though the death of his youngest son devastated him and he passed away a year later. Quentin Roosevelt remains the only son of a current or former president to die in combat.

Archie also fought in WWI, where he served as a captain in the 26th Infantry Regiment, part of the 1st Division. Horribly wounded in the leg by shrapnel, he was declared 100% disabled by the army and sent home. He commenced a career as a businessman, his reputation somewhat tarnished by his tangential association with the Teapot Dome scandal that everyone remembers hearing about in history class but no one can recall exactly. When the US entered WWII, Archie used his connection to his cousin Franklin, then president, to waive him back into the army. He served in the Pacific, this time as the Lt. Col. of one of the battalions of the 162nd Infantry Regiment in New Guinea. There, he was again horribly wounded and again evacuated and again declared 100% disabled. He remains the only man to date to have this distinction.

Check it out. Albert Fall was probably a murderer.

In addition to being the most militant -in the purest sense- of the Roosevelt boys, Archie was also a committed political crusader in the mold of his father. By far the most right-wing of the Roosevelt children, Archie devoted the rest of his postwar life to uprooting communist subversion wherever he found it, which was pretty much everywhere, including- to his constant and furious dismay- at his alma mater, Harvard. Sadly, this also represents the greatest defeat suffered by the Roosevelt clan, as communism has not, to say the least, been excised from the Ivy League. Archie might have been an American Pinochet had he not had a penchant for getting blown up too often to continue his military career, with presumably only better medical record documentation keeping him from violently pursuing commies into the jungles of Vietnam. He passed away in 1979, the last of Roosevelt’s children with Edith.

Ethel most fully embraced her father’s love of public service, a quiet and devoted matron of charities and public causes throughout her long life. Unlike her older sister, who loved the limelight, Ethel embodied the WASP ethos of never appearing in a newspaper unless it was announcing your birth, wedding, or funeral. She was the solid one, the secure center around which the rest could align themselves. Never a beautiful woman (the Roosevelts were not an attractive bunch as a whole), she nonetheless married well and happily to a surgeon named Richard Derby. But unassuming as she was she was no less courageous than her brothers. Shortly after WWI began, Ethel, then 22, made her way to France alongside her husband and served as a nurse in field hospitals. This was in 1914; she arrived long before her brothers got there. It is difficult to imagine the pure horror that a young woman of her social class must have experienced thrown into a cauldron of wounded, dismembered, and traumatized men, men the ages of her brothers, torn and screaming and dying. Nurses worked alongside the surgeons- during big battles this meant sometimes for thirty-six hours at a stretch. Much was learned about shell shock during the war, but little of that knowledge was applied to the female medical staff who hadn’t been in actual combat. They did learn, however, that the ships transporting the nurses back home had to be encircled by chaser craft at all times- to rescue all the jumpers. In her official portrait Ethel appears in her Red Cross uniform, rather than the expected formal gown. She survived the war and no small amount of family tragedy to die shortly before Archie in 1977, aged 86. Only he, she, and Alice would reach old age.

Kermit was his father’s favorite travelling companion, the most gifted sportsman of the bunch and the most adventurous. He accompanied his father on his famous African Safari in 1909, where they killed something like 500 animals between them. Unlike his brothers, Kermit joined the British Army during WWI, seeing action in the Middle East, only later resigning his British commission in favor of serving in the AEF. He was a brilliant natural linguist, learning fluent Arabic in a month, and was preferred to the natives for his translation ability. After the war he became a businessman in South America, mastering Spanish and Portuguese, and again accompanied his father on another trip, exploring an uncharted arm of the Amazon River in Brazil. The trip did not go well, with both father and son becoming seriously ill with malaria, but they succeeded in documenting the region. Kermit would later travel with his brother Ted to Asia in pursuit of the giant panda, as having heard of this peaceful and reclusive animal they were overcome with the powerful Rooseveltian urge to shoot one, which they did, along with hundreds of other animals.

Unfortunately, Kermit inherited some of the darker family traits. The Roosevelts were prone to two debilities- alcoholism and depression- each with the capacity to be fatal. Their uncle Elliot, the father of Eleanor, had succumbed to both, and though he escaped any inclination to over-drink, at many points in TR’s own life what looked like fearlessness could be argued to in fact represent a death wish. Depressed people are very much like sharks; they have to keep moving or they suffocate and sink. Apart from the familial predisposition Kermit had seen great horrors both at war and in the jungles of the Amazon, and when not engaged in some activity that demanded the full exercise of his considerable powers he tended to brood, drink, and self-destruct. To the consternation of his family he engaged in repeated and embarrassing benders. When WWII came about, he managed to wrangle a commission like his surviving brothers, but to dry him out it was felt best to send him to the middle of nowhere. Bored and lonely, suffering from the effects of malaria, prior service, and his own demons, Kermit shot himself in 1943. They told his aged mother it was a heart attack. As a postscript, Kermit’s son, Kermit Jr., otherwise known as Kim Roosevelt, served in the OSS during the same war. Afterwards, he would join the CIA and orchestrate numerous clandestine operations, including the overthrow of the socialist government of Iran in 1953.

Ted, the oldest son, had always carried the greatest burden of expectation. He was not only the first son but bore the name of the man TR most admired, which meant there was never any chance he would be allowed to lead a mediocre life. As recent examples show, being the child of a prominent person can be a suffocating prison, especially when opportunities abound for trouble. But Ted, perhaps more than any of the others, rose to the occasion of his birthright.

He was the first of the lot to go to Groton, part of the then-novel network of prep schools designed to feed into the Ivies. Spartan places that harbored a culture of bullying on the British model, these schools were designed to toughen up future leaders, and Ted was given no passes because of his lineage. All the Roosevelt boys would attend school there or similar institutions. He played football despite being undersized, repeatedly breaking bones. It should be noted here that TR was fully aware of the burdens his children shouldered, most of all his eldest son. He understood from both personal experience and his broad knowledge of the lives of great men how hard it is for a heathy plant to grow in a shadow. Without Ted knowing, he passed word to the coach to bench him. TR was a demanding father, but he was first of all a loving one, and though no one is perfect, he knew his duty to strike a balance and had the sense of discernment to know when to push and when to pull back. He had his father’s own example to thank for that.

Ted fought in WWI, where he was wounded and gassed. Like his brother Archie, he was caught at the edges of the Teapot Dome scandal. He tried to run for office, but never quite got off the ground with his political career; while earnest and certainly talented, he lacked his father’s charisma. He didn’t especially mind. Ted stayed in the Army Reserves and kept up his training, and by the time WWII came around, he had been promoted to full colonel, soon to be made a brigadier general. Like his brothers, he used his rich guy connections to get a spot in combat, going to North Africa as commander of his old outfit, the 26th.

Ted was not the typical WWII officer. He preferred to lead from the front rather than coordinate at the rear, which was not good leadership as far as many of his fellow officers were concerned. George Patton, his overall superior, also disliked his easygoing manner with the enlisted men and his general indifference to spit and polish; he viewed Roosevelt as an over-eager dilettante, “brave, but otherwise no soldier.” At one point Patton relieved both Roosevelt and the latter’s division commander, but Roosevelt wrangled another post, this time as the deputy commander of the 41st Infantry Division, then stationed in England in preparation for Operation Overlord, the amphibious invasion of France.

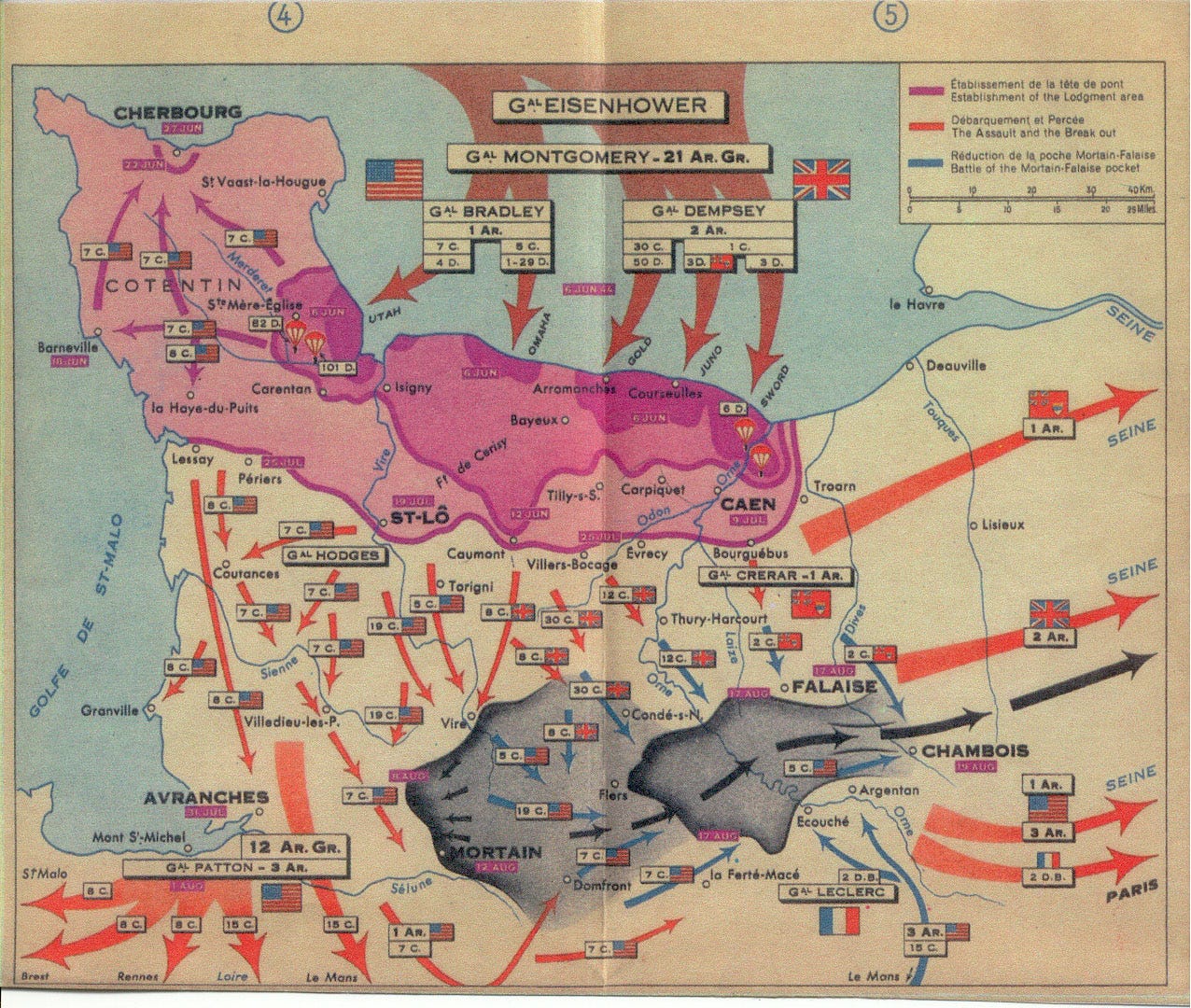

Roosevelt fully understood the high stakes and high risk of the operation. As originally intended, lower-level officers would lead men on the initial invasion, with higher ranks moving in after the beachhead was secured in order to coordinate further. He saw this as a bad idea, believing that someone of field grade should be on hand at the outset. Naturally, he believed it should be him. He managed to convince his very reluctant immediate superior of the necessity of his presence, and thus, Ted Roosevelt would hit Utah Beach at Normandy with the first wave. He was actually one of the first to put boots on sand.

It should be noted here that he was first of all, at 56, by far the oldest man in the invasion, more than twice as old as most of the enlisted men around him. His son, Quentin Roosevelt, was a captain in charge of a unit hitting Omaha beach a few miles away. Furthermore, his WWI injuries and age had left him with arthritis so debilitating that he had to walk with a cane. Yes, imagine Saving Private Ryan, and then picture that opening scene with a man in the midst hobbling along, propped up by a walking stick. Witnesses reported his unbelievable calm in the midst of the death raining down, even as he realized they were in the wrong place. But Ted quickly realized this represented an opportunity, as their incorrect position was actually better than the intended one, and thus he stood on the beach waving his cane to indicate to the next wave to move to the improvised spot, proclaiming to his subordinates, “we’ll start the war right here!” In other words, he turned his back to the German machine guns and artillery and stood in the open swinging a stick above his head in order to attract attention as someone obviously important. The men who landed in those subsequent craft uniformly remarked on Roosevelt’s relaxed manner. He recited the poetry his father had taught him in the midst of it all.

He was also dying. No one else knew, not his superiors, not even his wife. His heart was failing him after a lifetime of the superhuman demands he had placed upon it. He’d had one heart attack by this point and knew another was due. But he kept fighting. In the subsequent weeks, his division pressed inland. On July 12th, he finally met up with his son Quentin, and they had a pleasant conversation for several hours. Ted betrayed no indication that he was in the midst of another infarction. His son having departed, Ted died peacefully at his command post that very night. He had every right to have spent his final days in peace and ease, having already given back to his country everything it could have expected from him. But Ted was the truest aristocrat among his father’s children, and as the scion of the family embraced the ethos of sacrifice to its fullest. He died with his boots on in the lands he’d conquered from his nation’s enemies, having been given everything, and having given everything in turn. Patton called him one of the bravest man he had ever known and served as one of his pall bearers. Like his father before him, he was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Not all of us can be heroes. But we can each of us do our part to raise them. Whether with boys and girls, rich and poor, this Fathers’ Day remember that you have the power, by your words and example, to blow a mere spark of potential into a flame of excellence, and that even if our fallen world has given you nothing else, if you are blessed with children, you can achieve the most profound form of greatness by shaping the future by way of the legacy you leave to it through the generation that comes after you. Let us all work to be the men we need to be to send forth those young people who will create the world we hope will live after us. The future belongs to those who show up for it, and we fathers will guide what those who get there will do, whether our example is positive or not. Say a prayer for me in that regard if you get the chance, and happy Fathers’ Day.

This is a good essay and contains many things about TR's children that I didn't know.

There is much to admire about TR in his life, but in my opinion his full story also provides great warning about failing your ultimate test.

The year is 1912. TR hasn't been President for nearly 4 years, having handed the office over to his designated successor William Howard Taft. There is a rumbling split in the Republican Party, largely led by TR (meddling in politics after leaving the White House) who believes that the Republican Party is not progressive enough (yes, that progressive, the definition hasn't changed much) and so he stands for the nomination. He is narrowly defeated as the party stays with the incumbent, and most note that TR had already served almost two full terms as President, seeing how he replaced McKinley only six months in. (Serving only two terms was tradition only at that point, started by George Washington. The 22nd Amendment would not be passed until 1951 after the unprecedented four terms of another President named Roosevelt. TR had previously stated all the way up into 1912 that he would not run again but changed his mind.)

Not to be denied, TR immediately stood up his own party, the "Bull Moose" Progressive party, largely splitting the Republican Party along the nomination voting lines at the convention. This not only handed the Presidential election to Woodrow Wilson, it also created Democratic Party majorities in both Houses of Congress. The Progressive Party would then work WITH the Democratic Party to create supermajorities in both some state legislatures and the US Congress. (Wilson ended up with over 400 electoral votes but won only 41.8% of the popular vote.)

What followed was perhaps the most destructive Congress in the history of the United States.

The 16th Amendment had been floating around state legislatures since 1909 looking for ratification and was largely understood to be a dead letter as the more conservative wing of the Republican Party wouldn't support it. With the team up of the Progressive Party and the Democratic Party, it was finally ratified in February of 1913. The Seventeenth Amendment was likewise ratified in April 1913 largely on the same wave of Progressive or "Reform" sentiment.

The Revenue Act of 1913 beginning the permanent Federal Income Tax was passed on October 3, 1913. The Federal Reserve Act was passed on December 23, 1913. And Woodrow Wilson went on to two terms, including getting the US involved in a European war and firmly entrenching the American managerial state.

To my mind, Roosevelt had up until 1912 already clenched a very nice legacy, only clouded by his strong support of the beginnings of the United States as a contender for world wide Empire. He allowed his personal ego and elitism to lead him to support the radical liberalism of the French Revolution, ideas I believe TR himself roundly rejected in his personal life. Although I find much to admire in his personal life, I feel he failed his ultimate test and I no longer consider him a great President or politician as it is taught by our national mythology.

Praying for you and your family this Father's Day. I obviously don't know you personally, but if you're inspiring your children the same way your pieces inspire your readers, they're off to a great start.