With all the recent troubles stemming from our degenerate leadership class facilitating an invasion of the US (and the West more generally), many have taken Christianity to task for ultimately being behind such rampant cuckery. Even those who concede that the real culprit is liberalism seldom deign to admit that that political philosophy is itself less an outgrowth of Christianity than a necessary expedient for mitigating various confessional claims of warring sects while cementing the newly-centralized governments of the Early Modern Era and their attendant middle-class bureaucracies and commercial concerns- the forerunners of the managerial class. Liberalism is a response to a breakdown in Christian unity, from which the West has yet to recover.

But how did Christians respond to the prospect of invasion in the past, when its cultural power was more in evidence? Supporters of the faith rightly point out that when the cathedrals were full, the borders were defended, and the various peoples of the West conceived of themselves as at once particular nations and bound to a more universal identity as believers. But some would have it that this is less an artifact of Christianity than the legacy of pre-Christian cultural forces. Critics of the Church point to The Germanization of Medieval Christianity by James Russell as evidence that Christianity was a largely otherworldly faith unconcerned with the practical realities of earthly life, over and against a Germanic culture that stressed kinship and engagement. The impetus to militant faith that so characterized medieval religiosity was therefor a product of sociology and biology, less any superstrate intrusive ideology. The implication for supporters of this thesis is clear: Christianity is a foreign import that weakens western man against foreign invasion by dissolving his rightful sense of ethnic self into an abstracted human unity that forces him to accede to demands placed upon him by needy foreigners.

The based world that might have been…

The thesis is interesting and at points plausible; certainly Christianity spread through insightful missionaries taking care to address converts in language and philosophy comprehensible to them. Celtic Christianity drew on pre-existing Druidic religious structures with the result thst monasticism was far more central to it than the episcopacy. Saints Cyril and Methodius created the forerunner of the Cyrillic script in order to introduce Christianity to the Slavs. Matteo Ricci, sent to China, studied (and translated into Latin) the Confucian Classics and other Sinic philosophy in the original Chinese before even attempting any conversions; Chinese Bibles use "道" (Dào/ “way, path”) for Logos- “in the beginning was the Dào.” St. Innocent of Alaska took his family to the Aleutian Islands, studied the local dialects, created an alphabet for Aleut, translated the Bible into Aleut, and wrote a book on Christian doctrine in that language, as well as authoring dictionaries and sociological studies on the Native Alaskans. Many such examples could be shown. But the notion that Christianity- and “eastern” religions more generally- stand antithetically opposed to the native traditions of the west along a “world-affirming/ world-denying” dichotomy is tendentious and not especially evident either historically or theologically.

There’s little that’s ostensibly “world-denying” about the Old Testament, for example, large sections of which concern ethnic feuds, bloodlines, wars, dynastic struggles, and laws governing the most minute aspects of daily life in communities. The Ancient Israelites were meant to live in a particular place according to a particular relationship to their tribal God, something that would have made sense to the Romans, or even the Aztecs. That the theologically deeper books, particularly Isaiah, gave metaphysical significance and universalized the ideas of universal ethical monotheism inherent to the Israelite faith in no way negate that God meant for his human creations to engage with their world. Christianity was the culmination of this dual understanding- in the world but not of it, made for eternity while living as mortal creatures, our families and communities meant to be reflections of divine relationships. How to live in the world is as Eastern a notion as anything Western.

If you think Buddhism is a solely a religion of serene renunciation, you might be a bit confused by the psychotically militant sects of yamabushi (also called sohei) from medieval Japan. Note the cowl and characteristic naginata for negotiating with government officials.

These were questions that engaged the earliest generations of Christians as they do today. The proof text cited by critics and cucks alike, Galatians 3:28 (“There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”) signifies that differences of race, class, and sex have no meaning in terms of being barriers to God’s love and the love we should show to those in Christ, but the categories are transcended, not dissolved. After all, Paul elsewhere embraced his Jewish heritage, established that men were heads of their households, and told slaves to obey their masters. Men have to live in the world as they await the return of Christ, and that means living under human government and its hierarchies, for which the Christian should have respect, even when the state is a persecuting force. The faith is a revolutionary political project only in the sense that it inspires a longing for the holy in those in place to change things.

Along those lines, Emperor Constantine I established the model for Christian government, sacralizing his office as being a secular form of Apostolate, the emperor as worldly bishop. His laws were informed by both pragmatic Roman experience and Christian notions of human worth. His wars were similarly posited as defense of a rightly ordered society against barbarians and usurpers seeking to destroy it. The Christian emperors that followed him did not bear the sword in vain either.

The model that came from this collection of influences would be labeled ‘synergy’ by later scholars. This denoted the close interworking of the distinct institutions of Church and state. The former gave legitimacy and moral force while the latter protected the worldly realm in the former’s name. The concept appears as early as the Ecclesiastical History of Eusebius, and informs the Justinian Code later that proved so foundational to later Continental legal systems. This meant no small degree of overlap between offices sacred and profane, but at the same time, there were clear boundaries maintained both by tradition and practical necessity.

In his official histories Procopius was quite laudatory of the Emperor; in his Secret History he described Justinian and his wife as literal demons sent from hell to destroy the Roman Empire. At least Trump’s haters go straight to the New York Times to vent their estrogenic spleens.

The society that emerged from the Late Antique collapse of the Classical world is commonly called the Byzantine Empire, though the inhabitants never thought of themselves as anything but Romans, nor outsiders as more than barbarians. The empire possessed a well-defined cultural identity based around Nicene Christianity, Roman political and legal norms, and the Greek language and attendant classical heritage. It represented perhaps the most thorough example of practical Christian nationalism in history, lasting around a millennium (depending on when you think it began) and provides numerous examples for those interested in the practical applications of Christian ideals to government and society.

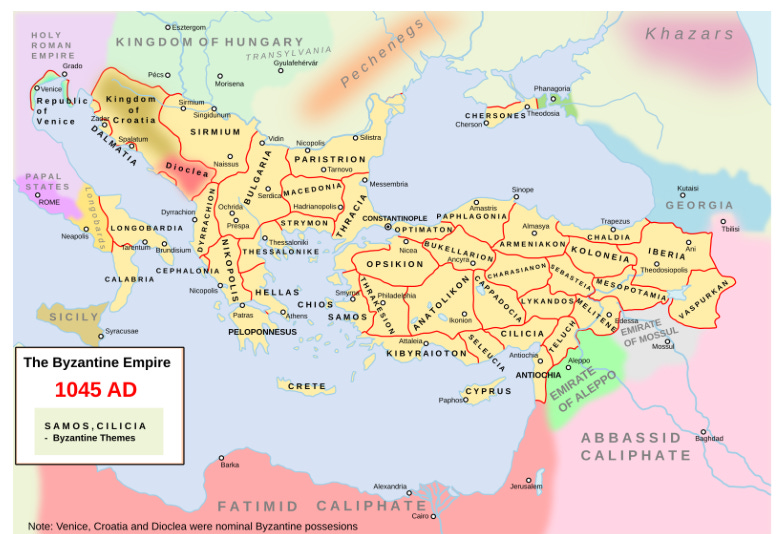

To begin with, however otherworldly the Byzantines would have preferred to be, the world around them was hardly conducive to a society of would-be monastic contemplatives. The Byzantine Empire had no natural boundaries, and the surrounding territories were occupied by either large and permanently threatening states (Persia, the Caliphate, Ottoman Empire) or smaller tribal kingdoms, behind which lurked more nomadic and predatory forces always waiting for an opening. The diversity and energy of these hostiles- various groupings of Slavs, Germanics, Arabs, Turks, Iranians, Mongolians, and others- demanded constant attention at ever-changing flashpoints. This meant leadership of a profoundly military character. However much an emperor- a basileus, reviving the Ancient Greek title for king- saw himself as an autocrat appointed by God, in practical terms he was either a successful combat general or soon replaced by one. The Mandate of Heaven for his dynasty was demonstrated through victory, and constant struggle made the empire surprisingly meritocratic.

Osprey: for when you think you’ve outgrown those Eyewitness books. Yes, they’re awesome as well.

The state was organized to prioritize military readiness and efficiency. The great armies of expensive barbarian mercenaries of Late Antiquity were phased out during the long Persian Wars of the 6th-7th centuries in favor of a new structure which would become the backbone of the empire during its apogee- the Theme System. The empire was divided into military districts called themes (themata), each of which was headed by a general (strategos) who had both civil and military power there. Each theme was further subdivided all the way down to the village level, where most citizens lived as farmers. Much as the Ancient Israelites held their land in trust from God, Byzantines were given free land with the covenant that each farm would supply a soldier.

The whole made for an interesting blend of classical Greek ideals with eastern centralization, an almost Jeffersonian vision of an agrarian yeoman militia wedded to a Hamiltonian vigorous executive able to harness resources on a continental scale. To counterbalance the obvious temptation to overweening ambition of any particular strategos, and to make sure there was always a supply of self-supporting soldiers, the Byzantine government ruthlessly cracked down on any grandees attempting to increase their land holdings and turn free men into tenants, realizing that a social system of rent-seeking would be destabilizing and result in a hollowed out military. At its best, it was an enterprise that paradoxically combined hierarchy and autocracy with egalitarianism and economic independence.

Supplementing this was a full-time professional army made up of various tagmata, or regiments. These were an elite, based in Constantinople and important strategic points, and included heavy cavalry, horse archers, and companies of young aristocrats (Hikanatoi) eager to distinguish themselves. The emperors also made use of mercenaries on a limited basis, usually for their particular skills or else because their service was part of the tribute offered by some subject people. These troops further offered the emperors security against any rebellious strategoi who’d developed an independent power base.

But even for a wealthy state wars were an expensive undertaking. In an empire of perhaps 12 million people, the whole of the regular army never exceeded the size of a modern division (10,000-20,000 men). Beset on all sides by enemies, it would have been easy to exhaust the treasury in a few campaigns, leaving the empire open to different foes. Well aware of this, the Byzantine state developed a long-term strategic philosophy, explored at interesting length in Edward Luttwak’s The Grand Strategy of The Byzantine Empire.

For reasons both practical and idealistic, the Byzantines saw war as a last resort. While they lacked what moderns would consider a professional diplomatic corps, there was no shortage of clever aristocrats wiling to live long-term among the various peoples who surrounded the empire, who both provided intelligence and acted as agents of influence. The Byzantines made full use of their cultural prestige, seeking to convert the barbarians around them to Christianity, creating a settled buffer zone of allies around them where possible. Tribes would be invited to settle areas rendered uninhabited by war or disease, trusting that the force of Byzantine culture would work to assimilate even large numbers of people to both Christian and Hellenic norms- largely successfully. The diplomats made extensive use of bribery as well as threats of shifting alliances. Both the Byzantines and the people around them understood that there was always another group still more venal behind the most proximate barbarians, and the Byzantines were past masters at playing tribes off each other. After the disastrous fallout from the Persian Wars, when both empires were rendered too weak to fight off the surging Arab Muslims pouring out of the southern deserts, the Byzantines never again made the mistake of creating power vacuums. They chastised their nearest foes, but if it became necessary to destroy them, they preferred to engage that group’s further enemies to do so. The Byzantine army was thus preserved to fight when absolutely necessary.

And so it was in 941, when the Vikings invaded. These were the Rus, otherwise known as Varangians, Swedes who, unlike the Norse and Danes, had migrated east, where they set themselves up as a ruling caste in what is today Ukraine. Like their fellows elsewhere, they were alternately pirates or merchants, depending upon the relative strength of whoever they were dealing with, and had created a lucrative trade for themselves selling European women to Middle-Easterners, among other things. Proudly non-Christian (for the most part) they had adopted the Slavic pantheon, which mirrored their Scandinavian one, their sharing a common Indo-European origin. Previous Viking experience with Christianity had surely given them the general impression that the strange men who worshiped a crucified criminal and hoarded treasures under the care of unarmed contemplatives were easy pickings. The Rus were not unfamiliar with the Byzantines; 80 years earlier they had launched an attack on the city that devastated the suburbs and placed it under siege for weeks before either ending with the miraculous intervention of the Virgin or the invaders getting bored and leaving, depending which source you trust. The emperor then had been Michael III, who was both away fighting the Arabs and carried the unfortunate nickname “the Drunk,” and was thus not especially effective. It’s a wonder the Rus waited eight decades to come back in force.

Thanks again, Osprey! Seriously, the whole catalog is peak bingeability.

This time, the Viking leader would be Igor, (Ingvarr) son of the wily Rurik, leader of the Rus, as much as anyone could be said to be. The charm of the family name, the prospect of immense loot, and Igor’s own evident talent for command allowed him to amass a force of perhaps 1,000 ships for a trip through the Black Sea to the Bosporus, where Constantinople and its riches awaited. He wouldn’t be alone either; accompanying the Rus would be their Pechaneg allies, a neighboring Turkic people who alternately warred against and alongside the Rus. Igor planned to take advantage of the absence of the current emperor, who was away fighting in the east as his predecessor had been during the last Rus assault. Ideally, he would overwhelm the defenses left behind and force entry into the city proper, loot and pillage, and make his way back home before anyone could be stirred to stop him. He had every reason to be confident; the Vikings were the best in the world at amphibious assault and their prowess in battle was legendary. What could a bunch of decadent townies do to stop them?

Unfortunately for Igor, the emperor this time was not an inept alcoholic. Michael III had been usurped by one of his former drinking buddies, the son of a peasant who he’d brought into his bodyguard due to the latter’s huge size and wrestling prowess. But that man, Basil, was both ambitious and talented outside the ring as well, and soon developed his own following, with Michael naming him co-emperor before the newly minted Basil I had his friend assassinated while the latter was characteristically intoxicated. Basil’s treachery had the paradoxically happy effect of founding the Macedonian Dynasty (Basil was from the Macedonian theme). Basil would be succeeded by his son (who may have been Michael’s son) as Emperor Leo VI, called Sophotatos (the most wise) for his brilliant scholarly pursuits. Leo had less success with family life; his father-who seems to have hated him- married him off to a saintly but offputting woman, and after her death he had three more marriages before finally producing an heir. But that proved more tenuous than he’d hoped, as he died shortly after his son’s birth, and the young Constantine VIIPorphyrogenitas (born in the royal purple) would endure a very uneasy regency under a powerful military commander named Romanos.

The closest we could get to that is Richard Nixon appointing King Kong Bundy as his replacement for Spiro Agnew, then upgrading him to co-president after a few too many scotch and sodas, with Bundy then founding a legendary dynasty both in the White House and the WWE.

Romanos came from a prominent family with the noble but comically unfortunate name of Lakapenos, so we won’t mention that again. Having been successful as both a general and an admiral (drungarios) he was motivated by both personal ambition and concern that the empire was in the hands of a baby, his former side-chick mother, and a bunch of eunuchs and personal enemies, and thus he acted decisively to secure the situation. He exiled the dowager empress to a convent, disposed of his rivals, and in the name of the toddler-basileus, had himself proclaimed co-emperor- the one who actually did things. Romanos I put down rebellions, stopped invasions, secured peace with the Bulgarian Empire to the north, and having done so, departed to fight against the Abbasid Caliphate in the Middle East. It was then that the Rus pounced.

As they had the last time, the Rus sought to test their foe by attacking the area near the capital first before assaulting it. They landed in Bithynia, directly across the Sea of Marmara from Constantinople, and with their characteristic ruthless audacity, began pillaging and- apparently for the fun of it- torturing the locals. It’s uncertain, but they were perhaps testing the response time of the nearest Byzantine force; with no one showing up to stop them overland, they were poised to sail across the Bosporus and take the city by sea.

But Romanos was well-apprised of their movements, having been informed of the advancing host by his new friends in Bulgaria. With the navy assisting with operations in the Mediterranean, there was little they could do in the short term, but Romanos didn’t slide into power without being a font of useful ideas. Remembering that there were a number of decommissioned naval vessels in Constantinople awaiting scrapping, he ordered them re-activated, had them crewed with anyone who could sail, and most importantly, outfitted them with a nasty surprise for the invaders.

The Byzantines were not merely the heirs to the culture of the Classical world, but its science as well. Since ancient times, military engineers had been brewing various concoctions of petroleum, naphtha, phosphorus, pitch and other nasty, flammable substances into a chemical weapon known as Greek Fire. The Byzantines perfected it and kept it a state secret (its exact composition is still unknown today), deploying it on ships through giant pneumatic pumps. Thus equipped, the hulks set out in pursuit of the treasure-laden Vikings.

It’s unclear, but the Rus must have turned around on their pursuers, perhaps reasoning that the small force would be worth destroying. The ad-hoc navy turned on the spigots and napalmed the Viking fleet. Longboats, covered in flaming ooze, turned to ash before sinking. The oily mixture sat atop the water and continued to burn, giving the Northmen the option of drowning or being roasted alive. Those who did manage to swim away were promptly captured. It was a total rout.

But this was but one prong of the offensive. Another group, this one led by Igor, had landed in Thrace, in northern Greece, where they engaged in their usual depredations. This time, the army was on the way. Catching the Vikings in retreat, heavily laden with loot, the Byzantines fell upon them, Rus fighting prowess no match for the steely professionalism of men defending their homes and empire. Those who didn’t escape were captured. The rest of the fleet was destroyed at sea, with only a few escaping, among them Igor. The captives were taken back to Constantinople and beheaded at the Hippodrome.

Igor wasn’t quite done yet, though. Over the next couple of years, he amassed a new and somehow even larger force, and invaded once more. This time, the Byzantine response was different; Romanos met them halfway at the head of his army and negotiated. Having demonstrated in their previous encounter that he was more than capable of defeating them, he had no wish for further bloodshed and expense when it could be avoided. To the Byzantines, there were neither permanent enemies or friends, only permanent interests. Destroying the Rus in a long and costly campaign would simply create a space for some other barbarians to fill. Plus, they were good material, and you don’t waste that. True to Byzantine form, everyone walked away happy. The Rus got enough treasure to go home content and the Byzantines gave them special trading privileges. In return, the Rus stipulated that they would accept Byzantine control of the Crimea and, most importantly, would supply warriors when summoned to aid the emperor. So long as peace held the advantage was all to Byzantium’s favor, as their cultural power would work its way into the fabric of Rus society as it had with so many other barbarians. Igor’s wife became a Christian at some point, and the warriors who made their way south to the city they called Tsargrad- the City of Emperors- came home impressed by the richness of life there, and more than a little conditioned by it. This relationship would evolve into the formal establishment of the Varangian Guard, a permanent tagma of mercenaries fanatically loyal to the Universal Autocrat. The Rus would become Christians at the hands of Igor’s grandson Vladimir, who, having converted, proceeded to stand as godfather over the whole of his subjects.

Igor’s end was not especially pleasant. Returning home, he sought to bully a neighboring Slavic people called the Drevlians into paying him tribute. They seized him through treachery and apparently tied him to two bent trees, which they then released, ripping him in half. But they hadn’t reckoned with his widow, who, though a Christian, was still a Viking. Her vengeance was, well, thorough…

She remains a revered Orthodox saint and the namesake for many Russian girls.

Romanos, Byzantine that he was, was capable of both great ruthlessness and great repentance. His guilt over the way he’d sidelined the infant emperor Constantine gnawed away at him as he grew older, and reflected that the son of Leo VI held far more promise than his own brood. He either abdicated or allowed his two sons to depose him, knowing that Constantine would certainly end up in power when the dust settled, and Romanos spent the rest of his days as a monk in a small island monastery, seeking forgiveness for his sins. Only about a third of Byzantine emperors died peacefully, and he was blessed to be one of them.

There are a number of lessons to be learned here. Open borders are not a Christian value, and leaving one’s population to be despoiled by foreigners represents an abdication of power entrusted to the soverign by God. While immigration can represent a positive, it must be in the interest of society and with the expectation of assimilation to Christian norms, which society should enforce as a both a practical and transcendent consideration. The integration of faith and statecraft was normative in the West (and East) up to the Age of Enlightenment and ascendant liberalism. Rightist models of good governance regarding migrants, foreign affairs, and sundry other areas have a rich heritage to draw upon. We should make use of it.

Christianity is against "The World". People confuse what that means. "The World" is Saturn, the black cube, the force of despotic demons that wish to drag humanity into its lowest nature and into death.

Sometimes being against the world could mean being a monk on a mountain and renouncing all possessions. But countless other saints have shown us that being against the world can look like building empires and waging war. "The World" can be fought on many fronts.

Excellent essay, as always in defence of the Faith. I imagine the hamburger guy will assail this comment like with the others as he tries to assign himself the role of homo-pagan defender of the faith.

But the fact of the matter is that Christianity and Nationalism have always walked hand in hand with one another. The fact of the matter is that for example the ancients or Medievals if you will of Greece, France and other places never did separate their Faith from their sense of themselves as a tribe. If anything a separation between them is odd and unnatural.

It is also why when writing a 'Great Romance' for any nation of Christendom you will never be able to fully extricate the Christianity from the work. I tried in my youth and there was always a sense that it wasn't quite right. It is only now as a fully matured individual who has come to embrace his Faith and love for his civilization that I can write to the fullness of my abilities for Scotland, France & Japan.

All that said, nice picture of Nixon there lmao. And this goes really well with the essay I'm writing right now for Mythic fiction and story-telling as being something that is Christian and Nationalist by nature.