It’s easy-and not wholly inappropriate- when one thinks of the American Revolution, to envision something with a decidedly New England cultural tinge. After all, most of the important events leading up to the War for Independence occurred there- actually, in pretty much one city, Boston. The Puritan malcontents who ran the area had long chafed at anything that threatened their religious freedom, their mercantile activities, or their freedom not to pay taxes. Their imperial masters back in Parliament, in the wake of the expensive French and Indian War, were inclined to impose their will on all three. Most everyone there from the erudite autist John Adams to his distant cousin, the Proud Boy-esque Sam Adams, was thus ready to throw down by 1775.

Sam Jackson was also a patriot.

But there were other groups in America with different reasons to hate the British government, perhaps none more thoroughly than the Scots-Irish. Originally inhabiting the border areas of England and Scotland, they were a proud and quarrelsome people, culturally distinct from both other Scots and the people of Northern England. When they were content to raid their peers in the opposing kingdom they could be left well-enough alone, but when the two nations fell under the rule of a single monarch, ultimately leading to the Act of Union in 1707, the Crown now faced the problem of these violent recalcitrants occupying the middle of what was meant to be a prosperous and homogenous Britain. There was also the problem of their being religious dissenters- all the Calvinist truculence of the Puritans without the leaven of their being otherwise peaceful and law-abiding. So the British leadership made a clever move. Much like modern urban governments with Section 8 vouchers, the establishment of the day decided to give their surplus ruffians free homes among people the government hated even more. But instead of enriching suburbs with extremely valuable vibrant diversity, the people of the borderlands were told they could have all the land they could steal from the Catholic Irish, provided they were willing to kill over it. And boy were they!

All the government in England had to do was leave them alone with their small holdings and Presbyterianism and all might have been well, but that proved beyond the capabilities of the state. Hounded and impoverished, many of these Scots-Irish looked further afield, to America. They didn’t really have a lot of money to buy land in the New World, but that hardly mattered to them. As soon as the boat hit the dock, they made their way far inland, past any line of settlement where anyone had bothered to survey anything, and just built homes wherever they felt like it. For a good number this meant western Pennsylvania, but the greater part ended up in the backcountry of Virginia and the Carolinas.

This caused no end of problems for all sorts of people. The land offices often had no idea that squatters- often armed and dangerous ones- occupied plots they were selling to actual buyers, some of whom were wealthy speculators. Many of these Scots-Irish had no problem moving into Indian territory and just chasing off whoever happened to be there, which of course could lead to the eruption of native violence against other white settlements, which would then require the expensive attention of the army. Among themselves they were fractious and litigious, equally inclined to sue and brawl- or duel, for those with pretensions to status. To the more settled people nearer the coast they often seemed barbaric, an impression not helped by gangs like the Paxton Boys descending from the far west intending to sack Philadelphia. But they were equally a people of tremendous energy and enterprise, and united in a common purpose, they were honorable allies and deadly enemies. More than any other group, they gave the South its cultural character- proud, independent, religious, violent, and family-centric. Their descendants still represent a pool from which a disproportionate amount of military volunteers are drawn.

The Revolution was as much a southern phenomenon as it was a Yankee war. The character it took on there was naturally different, though, and in many ways more chaotic and destructive. The Scots-Irish were a major factor in this, their characteristic mode of small-scale clan based reaving lending itself well to the ad hoc militia forces raised throughout the region. In particular, two battles there- King’s Mountain and Cowpens-, small but profoundly important, illustrate the ways in which the distinctive characteristics of nascent Southern culture shaped the course of the war, and the way it is still remembered today.

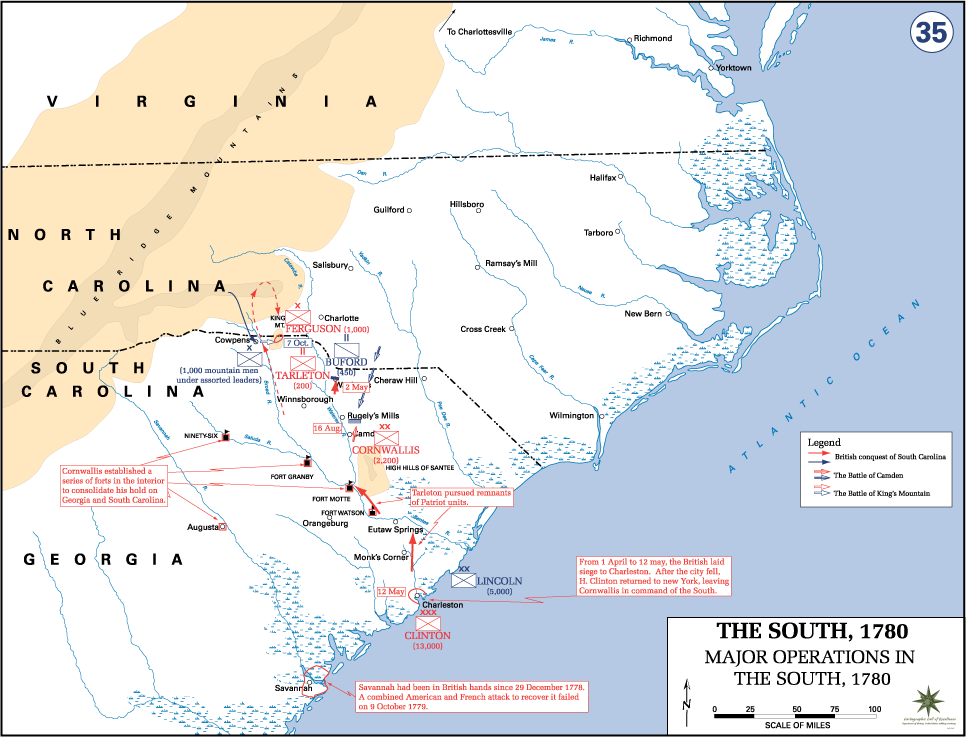

By 1780, the British had been fighting to suppress their rebellious North American colonies for nearly five years. While they controlled a number of major cities, the Continental Army was still in the field, and still surprisingly formidable. By defeating the British as Saratoga in New York in 1777, the Americans had earned enough clout to secure French recognition and an alliance, which for the British now meant a global conflict with a major power. Clearly, this irritating war in the New World needed to end.

The King’s Cabinet settled on a new strategy. Fighting the rebels in the north had proven largely indecisive. Why not focus on the South? High command was very receptive to the rosy picture painted by loyalists flocking to London of great hosts of southerners just waiting to be recruited into militias to fight for the crown, forces much cheaper and much more expendable than regulars. On one level it made a lot of sense; unlike the bothersome dissenters in New England, the southern colonies had an elite of Anglican grandees who lived like British landed gentry. Surely they would jump at the chance to fight for George III. The British already controlled Savannah, one of the only two real cities in the South. All that remained was to build on the previous success.

So it was that new commander-in-chief, General Sir Henry Clinton, ordered an attack on Charleston, South Carolina (the other city) in early 1780. Clinton- a difficult man who seems to have quarreled with all of his fellow officers, both subordinates and peers in the navy- commanded the siege personally, and despite the difficulties of launching an amphibious, combined arms assault, took Charleston in May, along with its entire garrison of 5,000 Continentals. It was a stunning and serious defeat for the Patriots, and seemed to bode well for the campaign as a whole.

After some further operations, such as the victorious Battle of Waxhaws in May, Clinton departed for the north, leaving his subordinate (whom he characteristically didn’t like), Major General Charles Cornwallis, in charge of the Southern Campaign. His job was to pacify completely the Carolinas before heading north to Virginia. To subdue the rebellious provinces, populated by close to 400,000 people, Clinton allotted Cornwallis about 3,000 men. He was told to recruit militia to make up any additional strength he needed.

Cornwallis’ push to do that would ignite a ferocious internecine conflict among the locals, especially in the backcountry. There the population was heavily Scots-Irish, and while few of them had any love for any distant government, they did have longstanding feuds with neighbors that flowed nicely into the scaled-up bloodletting opportunities the war promised. They joined rival militias, some only ostensibly under any higher command, and proceeded to burn each other’s homes and commit sundry other atrocities. It was arguably the most horrific fighting in the Revolution.

Cornwallis engaged two deputies to move further afield and secure his flanks with armed locals, while he himself rode off to fight the main Patriot army in theater near Camden, South Carolina in August. His foe was Major General Horatio Gates, who had been in command of the Patriot forces at Saratoga. Many people suspected that Gates was a blowhard who took credit for the work of subordinates and lacked actual talent as a leader, a thesis confirmed when Gates- who outnumbered Cornwallis two-to-one at Camden- not only lost the battle in an utter rout, but was last seen fleeing the scene as fast as his horse would carry him. It was a disaster for the Americans, who for the time being were left with nothing but bands of militia acting on their own initiative while the British consolidated their gains.

Bart Simpson’s succinct but trenchant summation of the career of Horatio Gates.

But British dominance of the region was paper-thin when it wasn’t wholly illusory. Like the Americans in Iraq, they were trying to do colonial pacification on the cheap. Clinton gave Cornwallis little in the way of money to pay his loyalist recruits, on the apparent theory that he could just tax the locals to get the cash he needed. Needless to say, this probably did more to turn the population squarely against the British than the deaths in battle. On top of that, those various local Patriot militia units, though uncoordinated, were still very active. Cornwallis had a plan, though.

One of the aforementioned deputies he sent out to deal with the rebel militia groups was Major Patrick Ferguson. Ferguson was a brave and talented commander who, among other things, had patented an early type of breach loading musket. It was too expensive to catch on, but his intelligence and creativity marked him as a man on the rise. Cornwallis sent Ferguson on a mission well-suited to his talents- he was to go to the far west of the Carolinas, to the foothills of the Appalachians, and recruit loyalist militia to suppress their rebellious counterparts. Ferguson set up a command post for his loyalists close to the border between the Carolinas near what is today Tennessee, and demanded that the rebellious locals lay down their arms, promising that if they didn’t, he would “lay waste to their country with fire and the sword.”

His begging to be made an example of attracted the attention of the local Patriot colonels of area militias- Isaac Shelby, John Sevier, Benjamin Johnston, William Campbell, and Joseph McDowell. The lot of them agreed to muster together under the overall command of Campbell and deal with Ferguson. These were the Overmountain Men, hardy hillbillies used to hunting and fighting like Indians, and to those joint ends were generally equipped with long rifles. These weapons were far more accurate than the smoothbore muskets favored by line infantry commanders of the day, who preferred the latter’s speed and volume of fire to the former’s precision. The top of the line longarm on the frontier was the Kentucky Rifle, more properly the Pennsylvania Rifle, as that was where expert immigrant German gunsmiths perfected the design. A beautiful and highly effective instrument often five feet long or more, in the right hands it had more than twice the effective range of the standard musket used by regular infantry. The disadvantage of the piece was that it was slow to load and a bit delicate; its long, thin barrel couldn’t mount a bayonet, which in the warfare of the time was a serious handicap. Such a weapon was really only practical for small companies of highly skilled light infantry, acting either alongside conventional infantry as a force multiplier, or, as in this case, as a fast moving strike force sent against an isolated target vulnerable to surprise.

Daniel Day-Lewis in full frontier rizz. This maniac actually lived in the woods the whole time they filmed Last of the Mohicans, and was an expert with his long rifle by the end.

And so it was that the militia group made its way after Ferguson, who, sensing something was coming his way, did the prudent thing and took the loyalists he’d raised on a march back toward Cornwallis, who now occupied Charlotte. Each body was around 1,000 strong. Like nearly all British officers, he had a low opinion of the effectiveness of America militia, and perhaps for that reason failed to move quite as quickly as he ought to have. One imagines he felt fairly secure setting up camp on the border-area ridge known locally as King’s Mountain. He didn’t anticipate that the militia pursuing him would acquire horses from friendly locals and ride at speed through the night, catching up to him on October 7th, 1780.

The surprise was total. Ferguson’s men only discovered the presence of the Overmountain Men when the rifle balls started flying. But Ferguson was no Gates; he took control of the situation immediately, formed up his loyalists, and prepared to engage. Some Patriots made their way up the gentle slope toward the front while others worked around to the steeper side and ascended more slowly. As they drew closer Ferguson ordered his ment to fix bayonets and charge.

The bayonet was essential to 18th century warfare, the decisive element of standard infantry combat. Bullets and cannonballs would soften up a foe, but rarely could they drive him off unaided. That was the job of the bayonet. It’s a weapon that requires very high discipline to use, or more importantly, to face. Even the bravest green soldiers, men who will stand under withering fire without flinching, will generally break ranks and flee in the face of a determined advance of men intending to impale them. American militia had a well-earned reputation for being willing to shoot but unwilling to stand a bayonet charge, a fact that the British had used to their great advantage when facing them.

And so it was that the Patriots scattered from the loyalist charge. But here their unique organizational structure worked to their benefit. Spread out as they were in largely independent tactical groups, and under no real central command, the various companies were immune to the infectious panic that would hit similar units organized into conventional lines. If one group was charged they simply fell back and came on again, moving from cover to cover, even as the other men around them kept converging. Ferguson was surrounded.

His men kept up a steady fire, but it was inaccurate. Line infantry marksmanship was meant to be directed at other lines, not well-concealed small groups. Firing downhill as they were, the tendency in any case was to err high. Realizing that he was cut off from relief, and that his only option was surrender or death, Ferguson- who was mounted and wearing a distinctive checkered shirt- used his sword to cut down the little white flags his men were attempting to hoist to stop the killing before he himself took a bullet and toppled from his horse. His boot remained caught in a stirrup, however, and his horse bolted, carrying him into the midst of the Patriots. He answered a demand for surrender by producing a pistol and killing the man addressing him, which prompted the others nearby to open up on him. He had seven bullets in his chest when they finally counted.

His men attempted to surrender, which was met with some unpleasantness. The war in the Carolina backcountry had featured some nasty and very recent atrocities, particularly at the Battle of the Waxhaws, where surrendered to Americans were (to some controversial degree) killed by vengeful loyalists. Some of the Overmountain men refused to stop fighting and kept firing into the loyalists even as they threw down their weapons and gave up. The officers took charge before a massacre could take place, but it was a near thing. It should be noted that Ferguson was the only British national at the Battle of King’s Mountain; it was otherwise a purely- and bitterly- American on American fight. Still angry at his last minute and pointless slaying of one of their comrades and mindful of his promise to devastate their homes, the Overmountain Men took turns urinating on Ferguson’s corpse before wrapping him in an oxhide and unceremoniously burying him, because f*** that guy.

Ferguson with the gun he invented. Fun fact, for some reason he brought his mistress to the battle at King’s Mountain with him, and she got shot as well.

Victory at King’s Mountain raised Patriot morale throughout the region and proved they were still very much in the fight. It also demonstrated that the great groundswell of loyalist sentiment the British were counting on was nowhere near what they’d hoped. The Overmountain Men operated with the expectation of civilian support, and, especially after their triumph, could no doubt continue to count on it. There was no force the British could call on in the area capable of suppressing them.

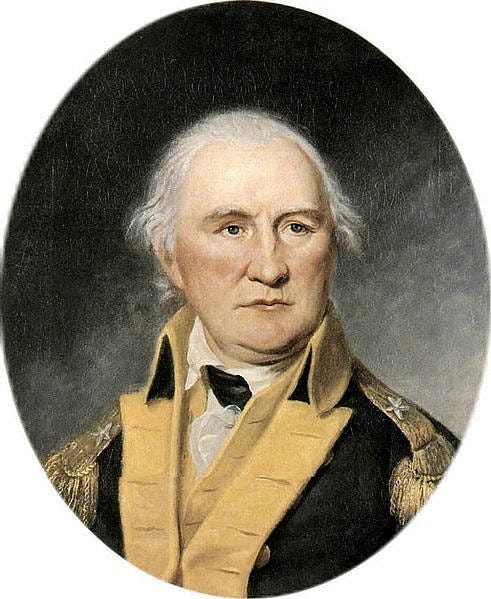

October of 1780 also saw another major development. With Gates presumably still galloping north, Major General Nathanael Greene had been selected to replace him as Washington’s theatre commander in the South. Greene was everything Gates was not- brave, self-effacing, and a born fighter. That he came from a Quaker background mattered little; he was a warrior, and more importantly, he recognized other warriors. To aid him in stemming the British onslaught, he called on the services of Brigadier General Daniel Morgan.

Nathanael Greene. Not pictured: Quaker pacifism.

Morgan was not technically Scots-Irish (his family was Welsh) but having run away from his New Jersey home as a teenager he lived among them in the Shenandoah Valley and absorbed no small amount of their culture as he clawed his way out of poverty. Even in a milieu of violent men Morgan stood out for his toughness and willingness to fight. He was a massive and powerfully built man, a natural leader, though in peacetime he spent a good bit of time in front of judges due to his fondness for liquor and gambling. His girlfriend taught him to read; he married her in gratitude. He became a teamster, what we would call today an owner-operator, though of a wagon and some oxen rather than a semi truck, which made him a man of some means. In that capacity he served in the French and Indian War as a contractor for the British army, where, characteristically, he got into a violent dispute with an officer and beat him up. He was sentenced to 500 lashes, which was supposed to kill him- it didn’t, and he later served in combat. There, he was shot in the back of the neck, the bullet exiting his mouth. That didn’t kill him either.

When the Revolution came around, Morgan was ready to roll. He received permission to create a company of elite light infantry armed with the aforementioned Kentucky Rifles, which he naturally led personally into battle despite being in his late forties. Washington took notice of him and gave him a bigger command, and Morgan would play a major role at Saratoga, for which Gates took credit. Disillusioned, he left the service, returning only at the invitation of Greene.

Note the scar above his lip. Few men take a bullet into their faces; fewer still have one fly out.

Morgan’s task would be to fight the other of Cornwallis’ lieutenants in the Carolinas. If Ferguson had been a bit supercilious, Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarlton could only be described in two words, the second being bag. The dissolute son of a slave merchant, Tarleton partied his way through most of his inheritance before realizing he needed to do something to stave off starvation and creditors. He therefore purchased a commission as an officer in a cavalry regiment (the then practice was for officers to post bonds for their good service) and became a soldier. He proved surprisingly good at it, so much so that he was further promoted without needing to buy the ranks, and by the time he came into Cornwallis’ employ in the Carolinas he had a solid history as a brave and hard-driving officer.

Tarleton created a mixed regiment of infantry, light artillery, and cavalry, including both regulars and loyalist militia, which came to be known alternately as the British, Tory, or Tarleton’s Legion. He led it to numerous victories, and his success gave him a fearsome reputation. But what really set Tarleton apart was his approach to the Patriots. Technically, everyone who took up arms against the king was guilty of vile treason, deserving of a Braveheart-esque punishment. In practice, however, British policy in the American colonies was to win hearts and minds and to treat the Patriot forces as de facto legitimate combatants. Tarleton disagreed with this, and regarded the Americans as so many deluded traitors. He despised the tactics of the local Patriot militias, and had no problem burning homes and confiscating property to send a message. Most controversially, it was his British Legion who had killed the surrendered men at the Battle of Waxhaws. Patriot propaganda had it that the cruel officer had ordered the slaughter of unarmed men; Tarleton claimed that he’d been trapped under his horse (shot out from under him while leading a charge) near the end of the battle, and his men, thinking he’d been treacherously shot, started killing prisoners out of justified anger until he quickly resumed control. But the word was out, and whatever happened, everyone knew that dealing with Tarleton meant a fight to the death, one way or another.

A later painting of Tarleton in his Legion uniform. The pose conceals the loss of fingers he sustained fighting at Guilford Courthouse.

Greene sent Morgan west from his headquarters near Charlotte with the goal of shoring up local Patriot support and gathering more men. He had under his command not only experienced militia from Virginia, but also around 300 veteran Delaware and Maryland regulars from the Continental Army, as well as cavalry units. Moving through the border area he was joined by a number of local militia units, including some who’d fought at King’s Mountain, and a substantial contingent from South Carolina under Andrew Pickens. It’s unclear how many men he had; as militia could come and go, and there is no exact contemporary record, it was somewhere between 1,000-2,000 under arms.

Tarleton, having been bolstered with regulars of his own, now commanding around 1,100 men, set out to destroy what he regarded as the latest batch of amateurs sent out to give his men saber practice. His plan was to move fast and destroy Morgan before he could consolidate any larger body of men. Discovering that Morgan had put himself with his lines of retreat blocked by the overfull Broad River, he saw his chance. This meant some hard marching, though. Over a 48 hour period his troops only got around four hours of rest as Tarleton drove them relentlessly, his only thought to destroy his foe while he was vulnerable. That his men were tired was irrelevant; he was, after all, chasing a bunch of farmers with nowhere to run. He was also unaware he was probably outnumbered significantly.

Morgan set up defensive positions in an area known locally as Hannah’s Cowpens, which featured a broad, open pasture and a low hill. He put his militia in the front, which was normally a bad idea tactically, as he knew militia were not inclined to stand and fight. But Morgan knew that Tarleton knew that as well. He was counting on it. He had some surprises in store.

Tarleton arrived on the scene at dawn on January 17th, 1781. True to form, he launched an immediate infantry attack on the assembled militia in front of him. True to form in turn, they fired two volleys before hurriedly withdrawing. Without further investigation, Tarleton sent most of his remaining troops into the fray, their goal to secure the top of the hill, while his mounted troops waited in reserve to run down the Patriots he expected would soon to be fleeing in every direction.

What Tarleton didn’t know was that Morgan had specifically ordered his militia to pull out. Their flight was feigned; moving around the base of the hill, they reformed out of sight. And cresting the hill, Tarelton’s confident troops discovered not a panicked mass of militia but a hard line of veteran regulars, who did not run. Firing at 30 yards, the Continentals’ musketry was devastating, many of Tarleton’s exhausted and suddenly demoralized men collapsed in surrender where they stood. For those further back, the regulars fixed bayonets and charged. Moving downhill at speed, they crushed the remaining Legion infantry there. Tarleton’s flanking forces were in turn met by the reformed militia on one side and Morgan’s cavalry charging out from the other. It was a rout.

Tarleton, like Ferguson, was no coward, and took the forty or so horsemen he still had willing and able to fight on a charge straight into the heart of combat, seeking to at least recover his field guns. Accounts differ as to exactly what happened next, but it was something like what follows. Seeing Tarleton, the commander of the American cavalry, Col. William Washington (cousin of George) charged him in turn. “Where now is the braggart Tarlton?!,” he shouted, and the two went at each other. A British officer struck at Washington, breaking the latter’s sword, whereupon Washington’s orderly shot the man. Washington parried a blow from Tarleton with his sword hilt and dealt him some kind of blow in return. Tarleton got off a pistol shot that grazed Washington’s knee before he was able to disengage and, seeing no further hope for any kind of success, fled the field with his few remaining men. The rest, his whole command, were either dead or captured.

Cornwallis kept fighting, and won a Pyrrhic victory against Greene at Guilford Court House that March, but his losses, coupled with the fact that the Patriots had control over the backcountry, meant that his position was untenable. The Patriots of the South had foiled British plans to pacify and draw recruits from the area, which meant that if Cornwallis was going to preserve his command, he would have to link up with other British forces, which meant in turn marching north. This led him, fatefully, to position his forces on Virginia’s Yorktown Peninsula, where he was trapped and defeated by Washington that October. The British surrender there marked the end of major battles in the war, though it would be two years before the Treaty of Paris (1783) formally ended the War for Independence with British recognition of the United States.

This Mel Gibson documentary tells the story with incredible fidelity. If I remember correctly, it ends with him personally spearing Cornwallis with that flag while saying, “It’s ‘pendance time!” Everyone in the theater cheered.

Raids and reprisals continued long after in the South, as partisans settled scores not accounted for by the peace deals of the powerful far away. Loyalists fled or blended into the new nation where they could. Veterans, like a young Andrew Jackson- who’d served at Waxhaws at 13- made their way west, where the Indian allies of the British were left to the mercy of the victorious settlers. There, as in the Revolution, the Scots-Irish were a major motive force in American expansion.

Andrew Jackson remains the only president to have been both a child soldier or a prisoner of war, much less at the same time.

Many of the leaders of the militia coalition that won the day at King’s Mountain became prominent men in the new state of Tennessee; John Sevier was elected governor. He famously quarreled with Jackson, which led to a semi-comical duel and a lot of bad blood. Greene bought a plantation in Georgia, where a visiting Eli Whitney would one day develop his design for a cotton gin. Morgan retired, but was called up once more when Washington and Alexander Hamilton needed his personal touch to deal with rebellious Scots-Irish frontiersmen in Pennsylvania, apoplectic over taxes on their homebrew liquor. Together, they managed to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion without violence, but secessionist sentiment on the edge of the new nation never really went away. Tarleton returned to England, where he was elected to Parliament, becoming notable for his strident advocacy to keep open the slave trade and sharing a mistress with the Prince of Wales, a personal friend. This latter relationship paved the way for further promotions, all the way to lieutenant general. He lost out to the Duke of Wellington for command of British forces in the Peninsular Campaign against Napoleon, however, perhaps due to his ongoing public disputes with carping critics of the British efforts to preserve their North American Empire.

It would be too much to say that the War for Independence was won in the South, by southerners, but their contribution, especially that of the often despised (then and now) rough rurals of Scots-Irish descent, was critical and decisive. In peace they caused problems for the peaceful; in a war they in turn were the bane of those who sought to harm their communities. Given some great work, their energy was and is unbounded. Their contemporary social woes are solely due to there being no good outlet for their ancestral motive urge to conquer.

This Independence Day Weekend, give a thought to the brave men of the South who fought so hard for their homes, and reflect that the current system of managerial neoliberalism is far more comprehensively oppressive than anything Thomas Jefferson experienced. Bear in mind as well that in history, things can move very quickly; it was not even a decade between total British triumph in North America after the French and Indian War and the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Things that seem quite secure are often the most ephemeral.

“The Battle of Cowpens” by William Ranney (1845). All pictures are from Wikipedia or the American Battlefield Trust unless otherwise noted.

I prefer the term Ulster Scots, because it avoids any confusion with the ethnic Irish, which I had to have a huge argument with my cousin about. Anyhow, one of my blood ancestors was in the first wave from Ulster to South Carolina in 1713, and his grandson was commissioned an ensign in the 2nd South Carolina in 1776, and later fought as a partisan under his old commanding officer, the Swamp Fox himself, Francis Marion. Too bad my ancestors didn't win their second rebellion in 1861. Also Patrick Ferguson's silk officer's sash was stripped off his body and John Sevier claimed it and it is in a museum in Nashville today.

If anyone's interested in a nice concise history of the Southern Campaign, check this out.

https://www.amazon.com/Road-Guilford-Courthouse-Revolution-Carolinas/dp/1620456028/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&dib_tag=se&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9.wuziFxcGJM0BUhI07rAbyW3uXW_K6jWl1UiLTKmUu5A.rDX3XlAccbVq57SiiGsnq16qxCKyeaEEsXo-w4xNjks&qid=1751746012&sr=8-1

Very well done and very educational . You write about military history very well and with a wide lens.