This piece was inspired in part by a note by Ruth Gaskovski

Whenever I introduce a new history class, I begin by asking my students, “what is history?” The answers I get generally fall into three categories. There are those who respond with some variation of the Santayana cliché; history is that which recurs if we forget it. More commonly, however, are those who answer by defining history as either our past or our memory.

Santayana fans everywhere

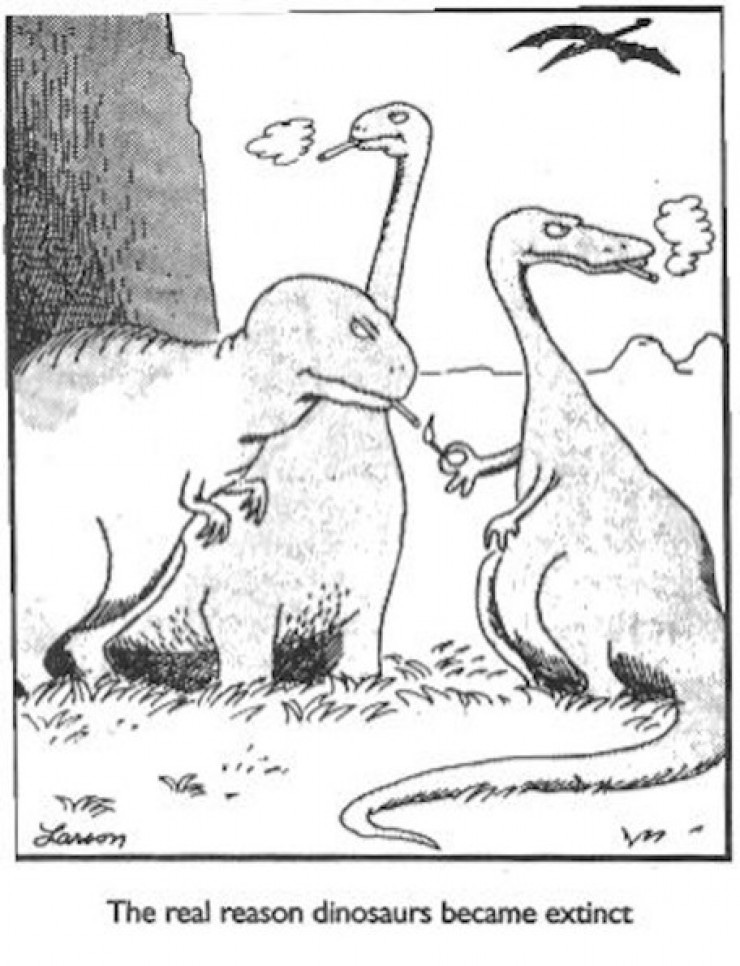

We spend a good bit of time breaking down both answers. The past extends back to creation, to a great cosmic explosion that birthed time and space, fiat lux. But stars and dinosaurs and the like are not really what we mean when we talk about history. I ask the students, “could one write a history of stars or dinosaurs?” The exercise would be both impossible and pointless, impossible because we both have no idea what stars or dinosaurs did in the past, individually or collectively, and pointless because, paradoxically enough, we actually have a good understanding of what they would be doing if we in fact had such evidence. Stars do what stars do, they are born in gaseous clouds, grow, steadily convert hydrogen into helium, run their course, and die in predictable ways, collapsing, exploding, disappearing. This is predictable mathematically. Dinosaurs were animals, and like extant animals, they roamed about, eating, mating, and being eaten in turn. Their modes of life are obvious from their fossilized bones, nature having written their story on teeth and claws and long limbs. To know one is to know its whole kind. Humans are the only weird things in the universe.

Where I learned about dinosaurs

But even when considered only in relation to humans history is not, strictly speaking, the past. Every human has the latter, but not necessarily the former. Consider: around 10,000 years ago what is now the Gobero region of the Sahara was a well-watered grassland, full of animals and their human predators. Between 8,000 and 6,000 BC, a group called the Kiffians lived there. They were giants, maxxing out on protein from the giant catfish they harpooned, and their bones reveal attachment points for huge muscles on their herculean frames. Then the desert appeared, and they departed, leaving only their graves behind. Around 5,000 BC the waters returned, and another group, the Tenerians, migrated to the same place, burying their dead in the same cemetery the Kiffians had used. More gracile than their predecessors, they made fine jewelry out of the bones and teeth of their prey, and dwelt in the land until around 2,500 BC, when the desert finally returned once more, where it remains. They probably merged with what would become the Egyptians to their east and the Berbers to their north, as the age of the hunter-gatherer came to an end in the MENA.

Above right: A scientific reconstruction of a Kiffian male, shown with a Late Cimmerian

That story is what their material remains can tell us, but otherwise, we know nothing, and can know nothing. Their names are given by scientists; we have no idea what they called themselves. We do not know the gods to whom they prayed, or the songs they sang to them, their heroes, their legends, their loves and hatreds. Aspects of their culture are humorously puzzling; what to make of the man buried with his finger in his mouth, or the one sent to the hereafter sitting on a turtle, or the one with his head in a clay pot? Sometimes, however, they become profoundly relatable. The most striking burial uncovered was that of a Tenerian woman with two children. They almost certainly died at the same time, but they did not die violently (both the Tenerians and the Kiffians were surprisingly peaceful, with none of the skull and forearm trauma often seen in Neolithic remains). Did they drown? In any case, they were buried together on a bed of flowers (pollen grains were identified in the sand) and facing each other. Whoever laid them to rest posed them holding hands. We do not know much about these people, but here human empathy can bridge an ocean of time; they, like we, knew death and love, and knew that the former could not conquer the latter. Beyond this, they must remain strangers to us. They had a past, and are part of our collective human past. But they did not and cannot have a history.

Seriously, this hits hard. Read about the site and the research here. Also, check out the picture at the top left and ask yourself why that guy isn’t playing the next Indiana Jones.

History is an artifact, a thing humans create out of the past. The past merely exists; history must be willed into being. The past in this sense is like a block of marble, the historian a sculptor, striking away in turn great chunks of time, then chiseling out years and months and days, then shaping what remains into a story. The purpose of this story is to answer a particular question or questions. History is not merely the recorded past, like a chronicle. It is the interpreted past, the past put to human use, at once a tool and a work of art. Like philosophy, its impetus is doubt. The work of history is to resolve that doubt by giving insight into human nature by means of examples from the past.

The first historian known by name, Herodotus, wondered how his people, the Greeks, were able to defeat the massive Persian Empire in a series of conflicts between 490 and 480 BC (he described his work as an inquiry, in Greek ἱστορία, or historia, hence the name). The Jews wrote history (the anonymous J source of the Old Testament corpus may in fact precede Herodotus), and the Chinese and Indians. Beyond that, history in the sense given here derives from examples from those cultures or else is non-existent. Modern humans have live on earth (so the scientists say) for around 200,000 years; writing came into being around 6,000 years ago, and Herodotus wrote his works around 450 BC. The vast majority of the human past is unrecorded and uninterpreted, forever outside of the reach of the historian, its stone having melted into magma, and is unavailable to sculpt. The past is ubiquitous; history is very, very rare.

Writing is necessary for history; it is at heart a written medium. While there is scope for orality, at heart history is only history if it relies on sources that have some physical existence against which assertions can be evaluated, and is itself such an artifact. As a product, history has an existence apart from the historian and the reader. It exists in a space as an object, tangible, visible, and permanent in the sense that, absent conscious intervention, it does not change (yes a book can rot, and someone can spill ink on it, but apart from that, a book does not change its contents spontaneously).

For this reason, saying that history is analogous to memory is misleading. While history relies on memory in part, and while history itself can be remembered, they are opposites. History, as noted, is a tangible product that exists apart from its creator in a space shared by others as an object to which other subjects can relate. Memory is entirely subjective, exists only within the individual, and cannot be shared (if you tell someone your memory, they do not have that memory, but only the recollection of you telling them about it). A work of history changes only through conscious effort. A memory cannot be consciously changed in this way (try to consciously forget something) but, insidiously, memories do change unconsciously all the time in response to psychological need. A boy gets dumped by his girlfriend and is beside himself remembering the good times they had. After a while, he reflects that she wasn’t especially interesting after all, and then after further consideration, wonders why he was with her in the first place, a process that culminates with him congratulating himself for getting rid of her to focus on his true passion, Pokémon.

And now he she is famous.

The digital age has given us an unhappy liminal space between those two opposites, a Hegelian synthesis of history and memory. Like history, the internet and everything on it (including AI) is a human artifact, with an existence distinct from that of its creators. Like memory, however, much of it exists in a malleable netherworld subject to change apart from the will of any human subject. It is also profoundly easy to alter, and to erase evidence of alteration. We are all familiar with the ‘stealth edits’ of media outlets, but would we know, really know, if all at once stories we all thought we knew changed en mass throughout the web? What if one night at 3:34 AM, Wikipedia and every major media outlet suddenly updated their spaces to reflect a new narrative that they had all stood heroically against Trump’s murder-vax despite pressure from Nazi Proud Boys and their leader, Vladimir Putin. What would it take for people to start doubting their own memories of the events of the past few years and to turn on neighbors who persisted in remembering what the right-thinking now understand was Tucker-generated misinformation? Would everyone recall with perfect clarity the time they saw Dr. Fauci on TV standing shoulder to shoulder with Joe Biden and Nancy Pelosi as they denounced Ron “Mäusenrein” DeSantis for closing the schools in the Sunshine State?

He personally held down and injected every kid in Florida with Zyclon-P(fizer)

The only possible check on this is physical media, which is why it is so important to preserve it. For my part this is easy, as I have always loved books as tangible objects. Much like the smell of leather, the scent that hits me when I enter a used book store is profoundly affecting; I can smell it even at I type at my kitchen table. Growing up, attending an awful and violent high school, I found solace in libraries. I carried books everywhere; I spent my limited funds on them, and over the years amassed a library I am very proud of. I think something like this is the way, to encourage in the young especially not just a love of information, but a real reverence for actual physical books. Give them as gifts, display them in your homes, and above all, read and set the example.

Of course, this idea extends beyond history, and beyond books. Preserve literature and science text; a time may come soon when even the most august authorities declare that there have always been 31 flavors of gender, just like Aristotle and Darwin said. Own music on records, tapes, and CDs, original art if possible, prints and reproductions otherwise. Prefer glass, wood, and metal to plastic, and plastic to e-anything.

As I write this, of course, I am aware that this essay will appear on the internet, in the ambiguous ether I am here decrying. If Substack shuts down, this work goes with it; if the system decides on a purge, I have enough keywords in my body of writing that my social credit score will be blasted into the screeching red zone. I am not anti-internet. It is a tool, one that I find useful. However I also enjoy a number of excellent publications that appear in print- IM-1776, Man’s World, The Asylum, etc., and such outlets deserve our support. For now, I print what I write and keep it on hand, a small gesture, but if the hammer ever drops, I can bury a folder in the woods in the hope that, in some better age, my work might be uncovered by some scholar with a trowel and brush, and that my words might serve to illuminate my own age, and answer some of the questions occupying the minds of the future.

I got a laugh out of the Conan picture. I honestly had no idea that Schwarzenegger was a Cimmerian and Wilt Chamberlain was a Kiffian.

It was a good article. History is supposed to be an unbiased recitation of our past, but as we all know, history is largely written by the victors or the corrupt.

Take, for instance, Afghanistan. There were a million Buddhas that once graced the countryside, but the Muslims that reside there now (Most specifically the Taliban) have blown them up. These same regressive desert-born rats also blatantly blow up pre-Muslim sites and destroy ancient hanging gardens and temples. They even move into new areas and destroy or repurpose cathedrals, thus eradicating history.

Elegant and thoughtful essay on what we talk about when we talk about history. I enjoyed reading it. Thank you!

On of the things I always try to remember about history is that all past events were once in the future. It sounds obvious, but it is exceedingly difficult to study history with the same mindset as those who made it. Unlike us, they didn't know what would happen.

robertsdavidn.substack.com/about