[With the recent state of the union speech, the arrival of a thoughtful and even-handed book, and recent comments from esteemed members of the media all warning of basically the same thing, I thought I might take a break from working on my fiction to visit a topic that seems to be ever so hot . . . ]

It was the spring of 1862, and things were looking up for the Union. Major General George Brinton McClellan had assembled the largest army ever seen in the Western Hemisphere and had contrived a clever plan- The Peninsula Campaign- to launch it in an assault on the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, just 90 miles from Washington, which itself was currently being menaced by Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston. He had only to land his army at the town of Urbana on the Rappahannock river and march it 50 miles west and Jefferson Davis would be fleeing with the silverware.

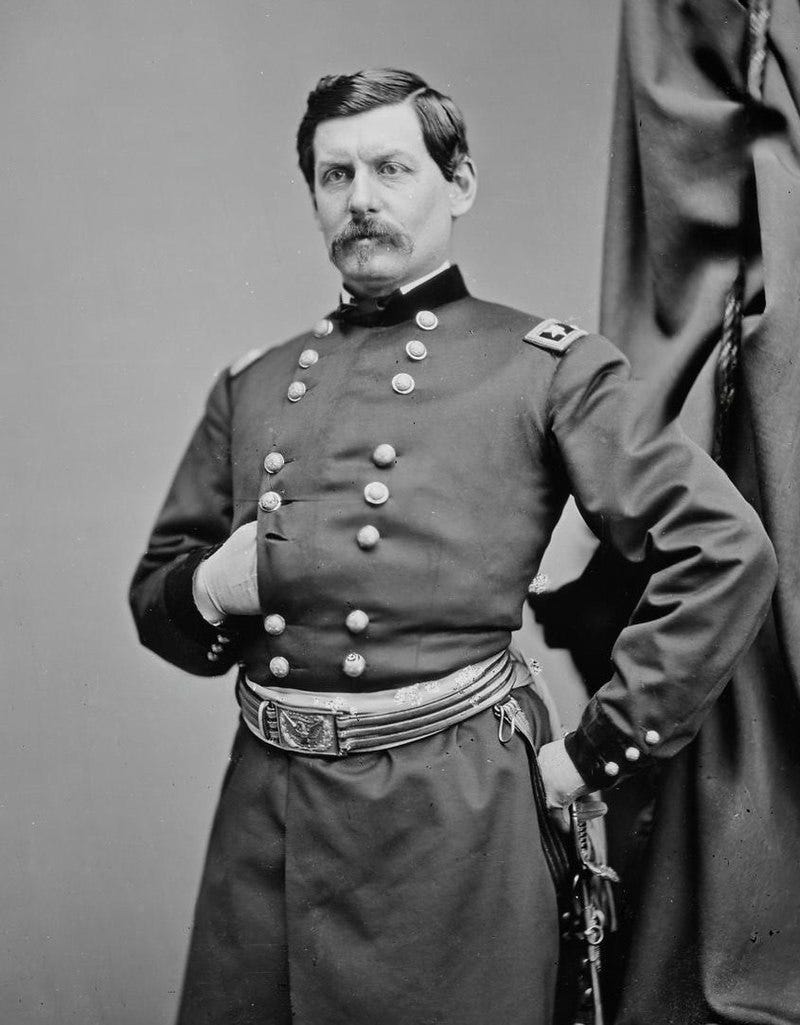

Unfortunately for the Union, McClellan was the purest example of a gamma male commander since Horatio Gates. Brilliant, physically brave, and outwardly gregarious, McClellan harbored intense insecurities and nursed deep resentments against those he considered inferior, a category which included everyone above him. In particular, the Democrat McClellan despised the Republican regime of Abraham Lincoln, whom he ostensibly served. And while he was a genius at organization and logistics- creating from nothing the Army of the Potomac he now commanded- when it came to actually hazarding his forces in combat he inevitably became fatally indecisive, terrified of bloodshed and bad headlines which would tarnish his reputation. So while a bolder man would have pushed his army forward and taken Richmond at all costs, mourned the dead and gotten himself elected president as the man who saved the Union, McClellan dithered, insisting that the the rebels had more men that he did (he generally outnumbered them 2-1) and allowed Johnston to make his way back from Washington to block his path.

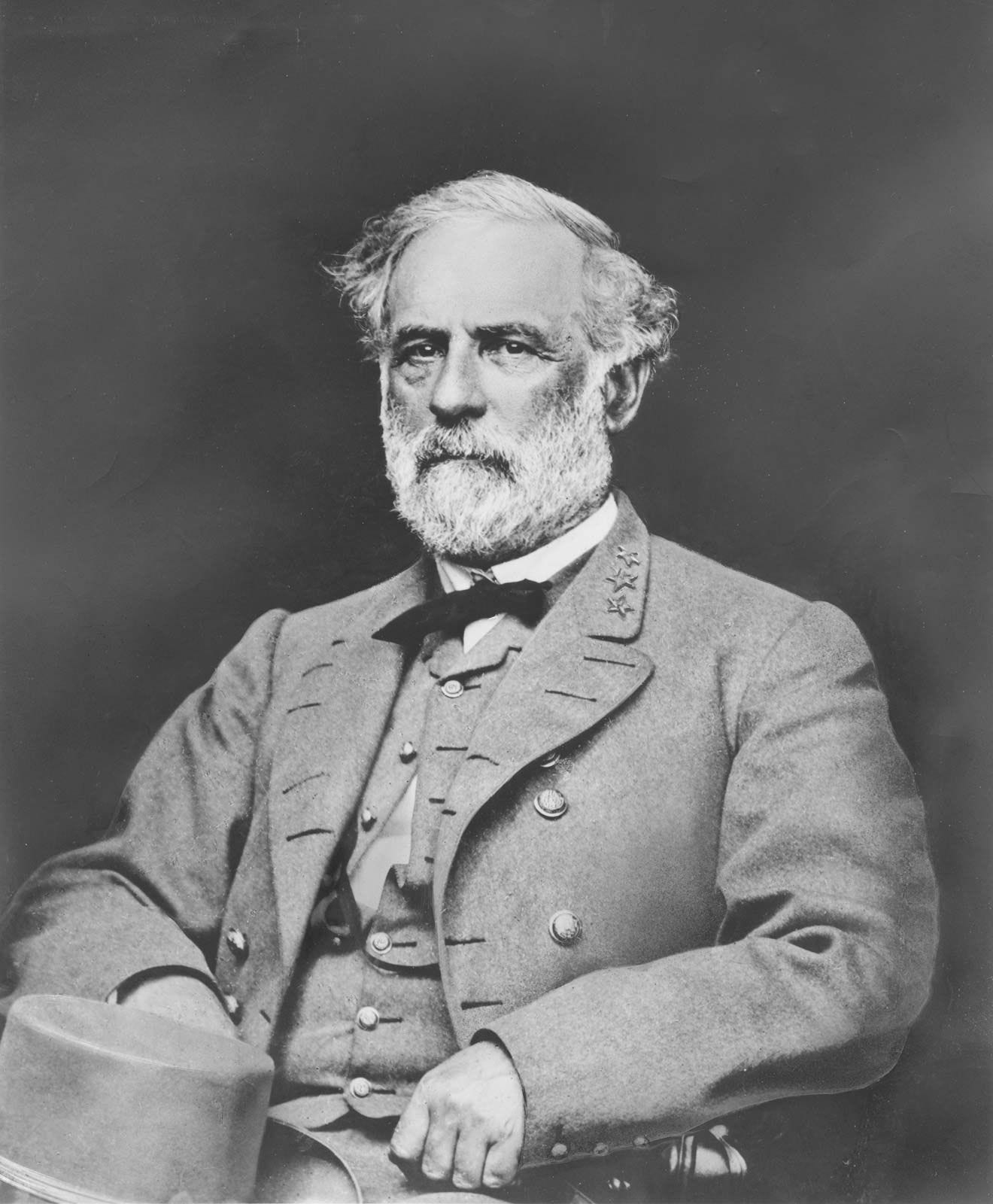

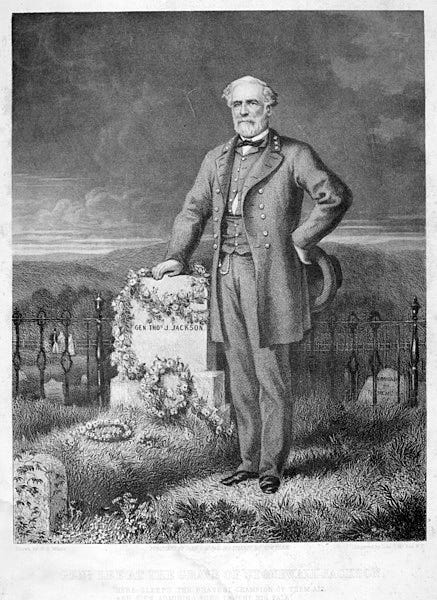

He and Johnston fought a number of indecisive battles, the main result of which was that Johnston was wounded and replaced by Robert E. Lee. While Johnston was a capable commander, Lee was a killer, his gentle, patrician demeanor belying one of the most brilliant, audacious, and aggressive military personas in American history. Rather than simply defend and be ground down by McClellan’s superior resources and manpower, Lee went on the offensive, sending his command, the Army of Northern Virginia, on a multipronged assault against his larger opponent.

Lee and his subordinates were new to operations on this scale, and the battles that followed, known as the Seven Days, were a series of near disasters and missed opportunities. Nonetheless, they had the desired effect of confirming for McClellan that he was indeed outnumbered (why else would the rebels be attacking?) and even when he achieved tactical victories he insisted on retreating back down the Virginia Peninsula. At Gaines Mill he simply disappeared from the battlefield, delegating when he should have been leading. Richmond was saved.

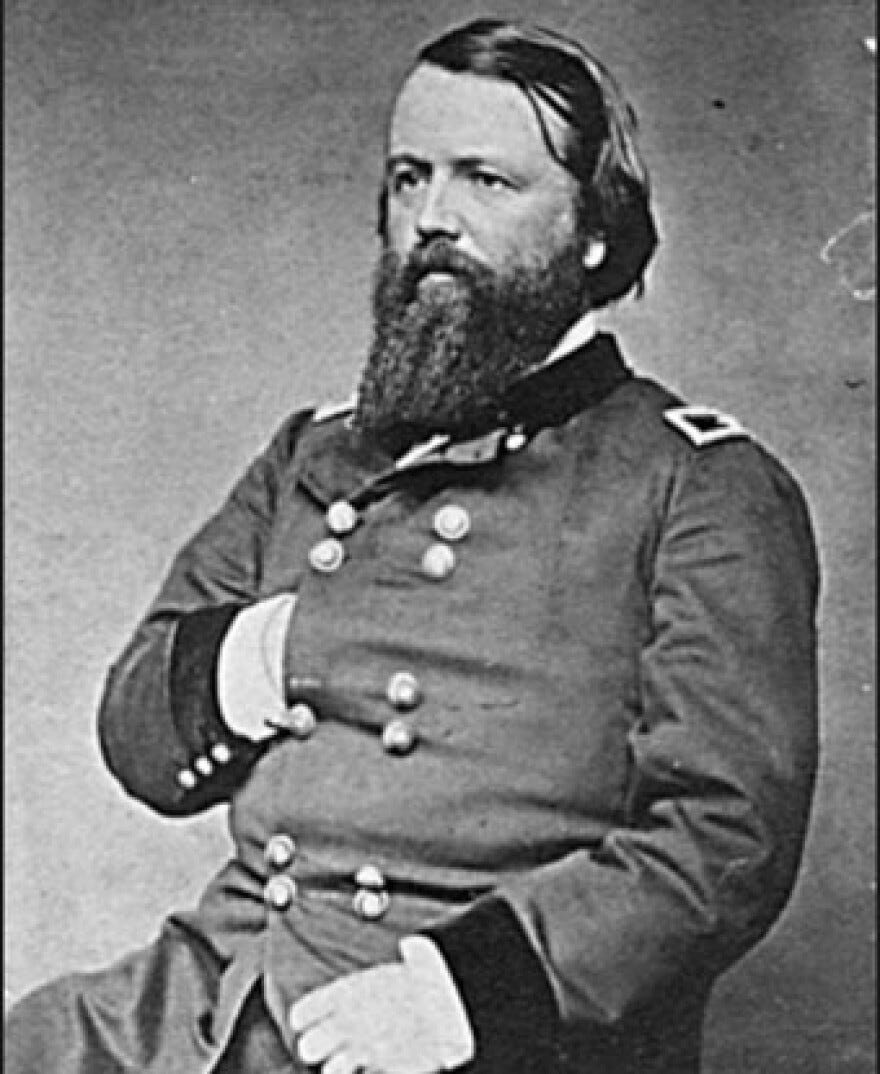

Lincoln was not happy. Unable as yet to rid himself of McClellan for political reasons, he decided instead to double-bank him, creating a second, more ideologically sound army to offset the Democrat general currently bunkered down in his estuary headquarters, angrily begging for more men to fight Lee’s phantom legions. He and his Commanding General of the Union Army, Henry Halleck (another risk-averse secret king), cobbled together units that had fought in the Shenandoah Valley into a new force known- confusingly- as the Army of Virginia. And to command it they chose not only a Republican in good standing but a personal friend of the president, Major General John Pope.

Pope had a few things to recommend him. For one, he had had a mostly successful career as a battlefield commander, notably capturing Island #10 from the Confederates and securing Union control of a good part of the Mississippi in the process. He was also a committed abolitionist possessed of a seething hatred of the “slave power” his co-ideologues in the Lincoln administration wanted to see brutally punished. Unlike the dithering McClellan, he meant to destroy the South, not reconcile with it. Naturally, the two men absolutely hated each other. Halleck’s plan was for Pope and the Army of Virginia to stand firm southwest of Washington while McClellan marched his Army of the Potomac up to meet him. Combined, the two forces would march on Richmond nearly 160,000 strong. Nothing that Lee had could stop them.

While McClellan passive-aggressively went through the motions of obeying his orders to get moving, Pope got busy with what he saw as his immediate and primary tasks, publicly mocking McClellan and punishing Southerners. These he accomplished through a series of proclamations. The first was his introductory message to his new command:

Let us understand each other. I have come to you from the West, where we have always seen the backs of our enemies; from an army whose business it has been to seek the adversary and to beat him when he was found; whose policy has been attack and not defense . . . I desire you to dismiss from your minds certain phrases, which I am sorry to find so much in vogue amongst you. I hear constantly of "taking strong positions and holding them," of "lines of retreat," and of "bases of supplies." Let us discard such ideas. The strongest position a soldier should desire to occupy is one from which he can most easily advance against the enemy. Let us study the probable lines of retreat of our opponents, and leave our own to take care of themselves. Let us look before us, and not behind. Success and glory are in the advance, disaster and shame lurk in the rear.

All of this was directed squarely at McClellan (the quotes are his words), which was obvious to all, especially McClellan. But it also had the effect of insulting the men now serving under Pope, many of whom had previously served under McClellan and wished to do so again, or else were trickling in, corps by corps, as McClellan slowly sent them to join his rival. One in particular, Major General Fitz John Porter, a close friend of McClellan, began writing letters to his comrade and others mocking Pope in terms that bordered on insubordination. Halleck did little to shut down the dissent and did nothing to clarify who would actually be in charge once the two armies united, thus leaving the two commanders to jockey for place by either being seen to win or not to lose.

Pope’s second task was to punish the South, which he did with a series of general orders that essentially spelled out that his army was to live off the land, confiscating goods from the local farmers and paying with notes redeemable by “loyal citizens” after the war. Anyone openly supporting the Confederacy would be treated as a prisoner of war and those who gave comfort to Lee’s army would be driven to ruin. It was very obviously a license to pillage, with the full backing of the Lincoln administration, which is how both his own forces and Lee saw it. Lee, not a man given to insults or feuds, who generally showed the same respect to friends and enemies alike, labeled Pope a “miscreant,” adding that he “should be suppressed.” This was as close to getting Lee-flamed as possible without the actual flames of combat, which, of course, the general was busy preparing.

Very well aware of the threat posed by the possibility of Pope and McClellan joining forces, Lee needed to prevent that, which meant defeating the enemy in detail. Pope, with the smaller of the two commands, made for the obvious first target. Lee also realized that Pope, simply by being where he was, threatened Lee’s supply lines, as the Army of Virginia loomed over the Virginia Central Railroad. But of course, most urgent of all was the simple fact that the Lincoln government’s forces were despoiling his countrymen. Fortunately for Lee, he had just the solution to that problem.

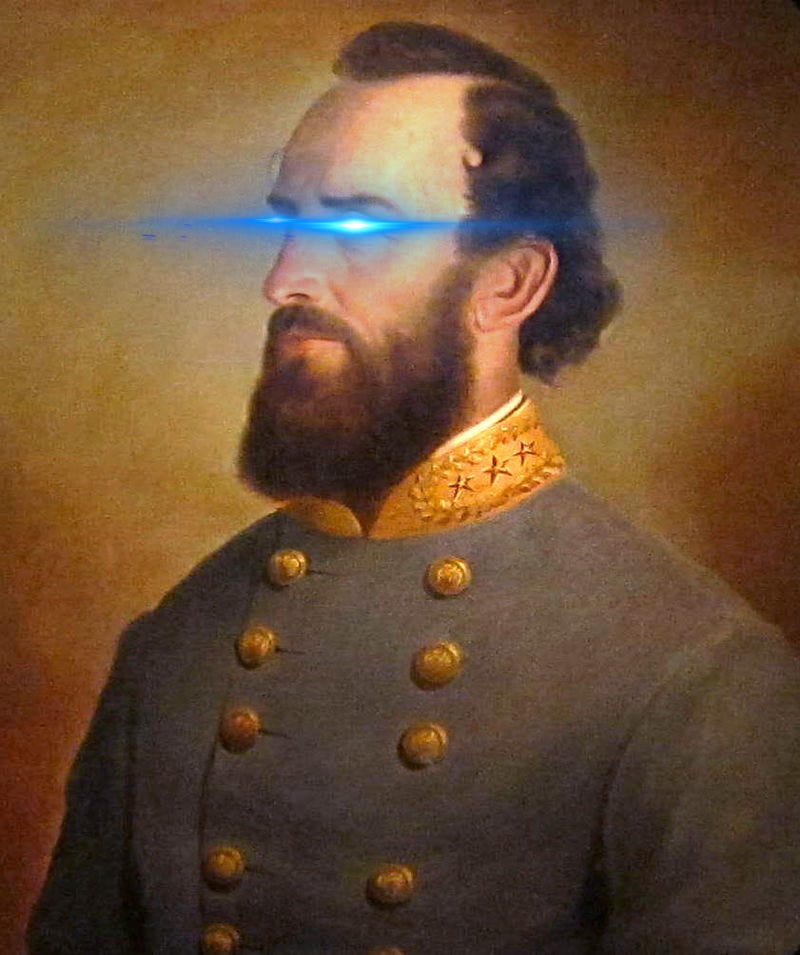

Thomas Jackson was born in the backwoods of what is now Clarksburg, West Virginia (then Virginia), and before the war had lived not far from the area now under contest. His early life had been marred by poverty and great loss- his parents and a beloved brother had died before he was a man, and his one remaining family member, his sister Laura, was no longer on speaking terms with him due to their taking opposing sides in the war. While Laura was a Unionist, Jackson, though initially opposing secession, had embraced the cause fanatically, which was the only way he embraced anything. From his days at West Point, where he began as a barely-admitted semi-literate and rose to being in the top twenty in his class, to his days in the Mexican War when he was promoted for bravery to brevet major, to his subsequent career as a professor at Virginia Military Institute, there was nothing he did that he did not put his whole being into.

This didn’t make him popular. Jackson was a quiet man of deep religious conviction, a dour and serious Presbyterian for whom all destinies were written by an inscrutable God. He was terrible at his teaching job, mocked by students for his quirks and severity. Despite his politeness and work ethic he tended to be regarded as an oddball and a subject of puzzlement among his neighbors. As he seldom even mentioned his war service, let alone his heroism, most people would have thought him best suited to being a supply clerk when the Civil War began.

Jackson quickly proved them wrong. Weird or not, the Confederate government needed people with experience, and Jackson was given a brigadier general’s commision just in time to earn his nickname at the Battle of First Manassas (known as First Bull Run to Yankees). Holding his position in the midst of a collapsing Southern line, Jackson stood like a stone wall, in the words of the doomed Barnard Bee, and his comrades rallied around him, driving the Union forces from the field to stampede over the Washington picnickers who had come out to see the rebellion crushed. He became a different person in battle, or rather, only in battle could the real man fully emerge. His slouched posture stiffened into upright fearlessness. His eyes blazed, and men swore he actually glowed (his other nom de guerre became Old Blue Light). He barely took notice of the bullets and shells flying around him, and a man who in peacetime was a hypochondriac prone to migraines and light sensitivity hardly acknowledged it when he was shot through the hand. Indeed, command seemed to cure all of his ailments and insecurities. One might even call his former condition Pre-TSD; the man was actually suffering physically and psychologically from not being in battle. His students had called him Tom Fool. His country now knew him as Stonewall Jackson.

His legend was cemented by his defense of the Shenandoah Valley, the breadbasket of the area around Virginia as well as being the back entrance into both Washington and Richmond. Time and again, he whipped the superior forces sent to stop him, led by the best the Union Army could then field. He moved faster than any man should have been able to march infantry and struck wherever he shouldn’t have been able to reach. He attacked when others would have retreated and moved when others would have stayed put. He specialized in hunting down larger forces and putting them to flight. His men loved and feared him all at once; he brought them victories but never hesitated to execute malcontents and deserters. He was just the sort of man to suppress a miscreant, and he already had a plan. Jackson was going to pick some fights.

He and Lee decided that Jackson would depart Richmond with his command and march to Gordonsville, which stood along the Virginia Central. From there, Jackson took the initiative, marching north to a place called Cedar Mountain. Also showing initiative was Union Major General Nathaniel Banks, former speaker of the house and a close Lincoln ally, who now commanded the II Corps of the Army of Virginia, positioned at the center of Pope’s widely-dispersed lines. He and Jackson had met before; among Jackson’s troops the Union commander was known as “Commissary” Banks due to the frequency with which they had looted Banks’ supplies after defeating him. Banks wasn’t really a bad general, just not as good as Jackson, and yet again demonstrated that fact by picking the perfectly wrong time to attack him, as Banks actually had fewer men with him at Cedar Mountain than Jackson did. The result was another beating on the 9th of August.

Unexpectedly for the Union, this time it was Jackson who retreated, moving back to Gordonsville, repositioning himself for what would come next. Lee had a bigger scheme in the works than Jackson simply bullying Lincoln’s friends as the opportunities arose. Having decided that McClellan was so timid that he could simply leave Richmond almost wholly unguarded, Lee had in mind an audacious scheme. His whole army would move to attack Pope, then turn on McClellan. To facilitate this, Lee sent his cavalry chief, James Ewell Brown (J.E.B) Stuart, vain and dashing but bold and brilliant, to assist Jackson in figuring out a way to get Pope to move out of the defensive positions he had, despite his earlier blustering, taken up as a result of Cedar Mountain. Stuart and Jackson then developed an even more brazen scheme. They would simply march around Pope in a broad arc, attack his supply base behind him, and dare him to do something about it.

Jackson had every reason to be confident; his men were battle-tested and eager. A good number of them came from this very area; some of his officers were the very boys who’d once mocked him at VMI. But in any case they were almost all the sons of small farmers, for whom immediate concerns centered on a government they regarded as foreign occupying the homesteads of their wives and mothers, helping themselves to everything like Penelope’s suitors. They had grown hard under Jackson’s rough tutelage, and they marched off now, stripped to the minimum, lean, weatherbeaten, and often barefoot, faster than softer men thought possible. Making eighteen miles a day, they moved undetected behind Stuart’s cavalry screen, arriving at Manassas junction on the night of the 26th moving into the morning of the 27th. There they encountered a huge bounty, supplies fit for an army of more than 100,000 men. Jackson and his men looted everything they could carry and lit the rest on fire. He then destroyed the rail lines that linked Pope to Washington, along with a fully-laden train that picked the wrong time to arrive.

For Pope, this was less a crisis than an opportunity. Jackson had gotten cocky, he reasoned, and now Pope could catch his foe retreating under the weight of his ill-gotten gains. He would have to march back to Gordonsville and safety, and all Pope had to do was figure out which route he was taking. Pope thus sent his commanders out hunting Jackson along every possible route. Marching and countermarching, grumbling under ever changing orders, it never occured to either Pope or his subordinates that Jackson wasn’t going anywhere.

Jackson knew the place where he’d won his nickname well, and had previously noticed a half-finished rail line being constructed at the northern end of the site. Sitting mostly in a woodline, with both excavated trenches and piles of dirt on hand, it made for a superb defensive position. It also sat along the Warrenton Turnpike, which any Union forces looking for him would probably be marching along. Jackson had his men set up there. Then he waited.

Sure enough, the next day, elements of the III Corps of the Army of Virginia, Rufus King’s division, made their way down the road, wondering where Jackson had run off to. Jackson helped them answer that question by opening fire as they passed his position. The smaller Battle of Groveton within Second Manassas served no other purpose but for Jackson to announce his presence and throw down the gauntlet. Having found Jackson and ascertained that he was there in full strength, the Union brigades that fought him retreated to rejoin Pope with the news.

Pope was overjoyed, as for him this information only served to confirm his previous theory. Jackson had been caught retreating, and now all Pope had to do was bring his army to bear on him, trapped in the woods. It never occurred to him that Jackson wanted to be caught there, or for that matter that fighting him was wholly unnecessary. This last part was important. Jackson’s whole plan hinged on Pope wanting to fight him. By simply staying where he was and waiting for McClellan to show up, Pope would be fully following his orders and able to combine with his rival into an unstoppable juggernaut. Even with his supply lines cut he could still live off the land as he had been, pillaging the farms of the area. Jackson couldn’t attack Pope, outnumbered as he was more than 2-1, so long as Pope hunkered down and fortified up. All Pope had to do was wait.

But the prospect of bagging Jackson was too tempting to resist for the man who’d only ever seen the backs of his enemies. Crushing the famous Stonewall would give him the political capital to demand full authority over the march on Richmond, which would in any case be a foregone conclusion with the wily Confederate defeated. He only had to bring his army to bear; the trouble was, he didn’t exactly know where it all was. Strung out chasing Jackson, the Army of Virginia was lost on a dozen roads, none of which the Yankees knew well. Again, he could have waited at least for that level of cohesion, but Pope feared the ‘fleeing’ Jackson would escape. He issued orders based on where he thought his commanders were and had them plan to attack on the morning of the 29th.

In theory, all of the Army of Virginia would move on Jackson in three places at once; what actually happened was that the only unit to attack was the I Corps of Franz Siegel, another political appointee given his job due to his ability to recruit German immigrants. Siegel’s men threw themselves at Jackson, then quickly retreated under withering fire and a fierce counterattack. By the afternoon, Pope had arrived personally on the battlefield and saw the mess firsthand. He rapidly issued new orders for another attack. Siegel and elements of the III and IX Corps of the Army of the Potomac would attack Jackson’s left and center, while the main thrust would come at Jackson’s right, led by Porter of the V Corps, the purpose being to cut off Jackson’s ‘retreat.’

Unfortunately for Pope, three problems hampered this outcome. First, Jackson wasn’t retreating, as those attacking quickly discovered. Second, the orders that Porter received from Pope made no clear sense and did not explicitly command him to attack. It is unclear why Pope was not more precise; he may have wanted to couch his order in vague language in case something went wrong (he had thrown Banks under the bus after Cedar Mountain), but if so, expecting a personal and professional enemy to take the initiative and attack Jackson was a dire mistake. Porter stayed put awaiting further instructions, which did not come in time. As it was, Porter staying in position actually had the unwitting effect of staving off disaster, for unbeknownst to Pope, there was a third problem with his plan- Lee had arrived.

Lee had marched both sections of his army around the unwitting Pope, first Jackson and now the wing commanded by James Longstreet. Stuart had coordinated the maneuvers and now guided the new arrivals into position, right on the left flank of Pope’s army. Ironically, Jackson and Longstreet formed a giant letter gamma around Pope, who was wholly oblivious to this unfortunate development. Lee wanted to attack right away, but Longstreet pointed out that with Porter so far to the south, a flanking maneuver would itself stand in danger of being flanked. Instead, they contented themselves with shelling the Union forces attacking Jackson until their offensive petered out.

The next morning, Pope was still confident. The better part of his army was now largely in place. The previous day had not gone well, but now he made sure everyone’s orders were very clear. Porter would attack Jackson’s right just like he should have the previous day. Finally accepting that there were Confederate forces to his right in addition to the ones before him, he somehow concluded, for reasons known only to him, that they were only there to help cover Jackson’s retreat He still could have pulled out in good order and united with McClellan. He could have done the prudent thing. But that would have made him McClellan, and he was John Pope.

For his part, McClellan had spent the last month doing everything he could to leave his opponent (Pope, not Lee) to twist in the wind. A mixture of insecure fear at imaginary Confederates and toxic jealousy of Pope kept him in extreme slow motion. It would be too much to say he wanted Pope to lose; he wasn’t a traitor. But that’s only because being a traitor would have required boldness he lacked. Instead he simply decided Pope would lose no matter what and that he wanted to be there to pick up the pieces of the army, repairing it as he had after the last loss at Bull Run. Halleck did nothing to fix this, other than to cover himself with correspondence that talked from both sides of the telegram. Lincoln failed to assert himself either, unable to make his will felt over the uniformed politicians he’d sent into the field. No one wanted to take ownership of the situation, leaving Lee, Jackson, and the rest to simply walk over and claim it.

Pope’s generals pleaded with him to rethink his strategy, but they were conniving backstabbers, and he was, in the words of author S. C. Gwynne, “a swaggering narcissist.” The pervasive culture of snake-pit animosity that characterized the Union military of the day made for a situation where every order and report was filtered through a lens of mistrust and scheming for advantage. The Confederates, poorer, less organized, and with far fewer resources were able to achieve what they did for as long as they did by cultivating a very different style of leadership in the person of Lee; rebel forces in the Western Theater, with problems like those suffered by the Union in the East, fared just as poorly. There is wisdom here . . .

And so the attack was launched. Porter moved forward, was repulsed by a Jackson who wasn’t supposed to be there and artillery fire from supposedly retreating men, then found himself on the receiving end of some 25,000 screaming Confederates pouring down from the ridge to his left, overwhelming him and driving him into his own lines to the right. The whole line collapsed in the face of fire from Jackson’s men and the flanking attack of half the Army of Northern Virginia. Only Pope’s last-minute quick thinking, combined with McClellan’s training and preparation of the soldiers, kept it from being a total rout like First Manassas, a sad testament to what the two might have accomplished were they better men. Pope’s campaign was over, and McClellan would never march on Richmond.

In the aftermath of the battle, recriminations fell like confetti at the parade no one would ever get. Pope was packed off to Minnesota to fight Indians, where his expertise at burning women and children out of their homes would be put to use where his flaws would least hinder him. He would spend the rest of his career doing this, joined by other starvation-tactic arsonists like Sherman and Sheridan. In the meantime, however, he managed to get Fitz John Porter court martialed, officially blaming him for the defeat at Second Bull Run. Pope was initially successful, but Porter would fight the ruling for decades, and achieved vindication during the Arthur administration when it was decided that Pope had actually been in the wrong. However, his plotting letters to McClellan and others were damning evidence that if he was not incompetent he was still willing to put his private feuds before the good of his army and country. No one emerged from the controversy looking good, nor should they have.

Lee invaded Maryland, and despite being heavily outnumbered fought McClellan to a standstill in the bloodiest day in American history at the Battle of Sharpsburg (Antietam) not even a month later. McClellan might have destroyed Lee had he been more aggressive; it was Fitz John Porter, not yet cashiered from the army, who urged caution at the moment he might have committed his reserves against a depleted Confederate force with its back to the Potomac. Instead, he let Lee slip away, and with it went his career. Lincoln finally managed the political will to replace him. Unfortunately, that replacement was Ambrose Burnside, which is its own story . . .

Jackson played the major role in Lee’s greatest battle, Chancellorsville. Taking his Second Corps on an even more audacious march than the one at Manassas, he surprised the XI Corps (the same unit, renamed, that had once been the I Corp of the Army of Virginia) under Oliver O. Howard. Like Jackson, Howard was deeply religious. Unlike Jackson, he couldn’t lead or fight very well. Howard was crushed and the Union line collapsed under Jackson’s assault. Sadly for the Confederacy, while conducting a personal reconnaissance as dusk settled, Jackson was accidentally shot by Confederate pickets as he returned to the lines. His arm was amputated, but he died of infection a few days after. His final words, “now let us pass over the river, and rest in the shade of the trees.”

Washington is the same cesspool of self-serving corruption as it ever was. The stuff to make soldiers is as it ever was. For the one who would become worthy, one with the will to lead and the courage to see hard things through, there is not only hope, but potential. The Popes of the world mock their presumed inferiors, not from frontier outposts, but from MSNBC studio chairs. The swamp still looses its minions on the people to loot them. The president treats half his country as a hostile foreign enemy. But for all their arrogance and disdain, they still remember what awaits them when when that white rural rage they despise and mock finds focus. And all the worse for them that that it’s no longer quite so white or so rural as they think. Nor, despite being outnumbered and harried, is it retreating . . .

This is one of your best. The connections you draw are so blatantly ignored by elites. Thank you

As a Christian, I've never realized (because, of course, it was never taught to me) that there is a great likelihood I'll see more Confederate soldiers in heaven than Union ones (south was much more religious, and still is). I think the obsession with slavery and race politics has completely clouded this truth from the church (and the public at large, obviously): there were good, God fearing men on both sides of this conflict, and it is sinful to slander the confederates as a bunch of racist evil heretics, regardless of if one believes their cause was justified or not. It is shameful that the civil war happened at all, and it is doubly shameful that there will likely be a second one.