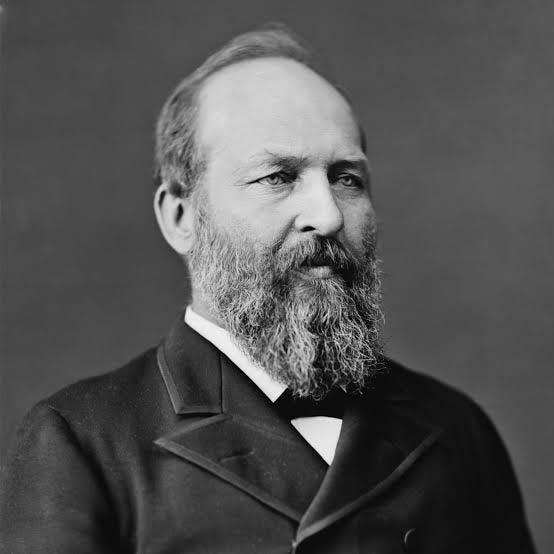

James Abram Garfield deserves to be better remembered. Were it not for the sad fate meted out to him by an assassin he would be so today, probably as one of the greatest presidents of the United States. But it was not to be. Another, very different man took his place, a man also largely forgotten by history. This, too, is unfair, for while Chester Alan Arthur was nothing so great as the man he succeeded, and indeed had shown little greatness in anything in his life to that point, he achieved, if not greatness, at least goodness, a goodness his country sorely needed at a time in which it was in short supply. And the story of how Arthur became that man is in turn bound up with a woman. Not a wife or a sweetheart or even a close friend, but a crippled recluse still more obscure to history, who saw something in Arthur that no one else did, and who reached out from her isolation to inspire him to be the man his country needed. Men can change.

If Garfield is thought of today, it’s as one of the parade of bearded non-entities who occupied the White House between the assassinated Lincoln and the successor to the assassinated McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt. The impression is that presidents of the Reconstruction era were generally shaped by forces rather than imposing their will upon them. The big personalities of the period were in the West or the boardrooms, gunslingers of one type or another. Politics was the backdrop to the drama we all remember, such as we do.

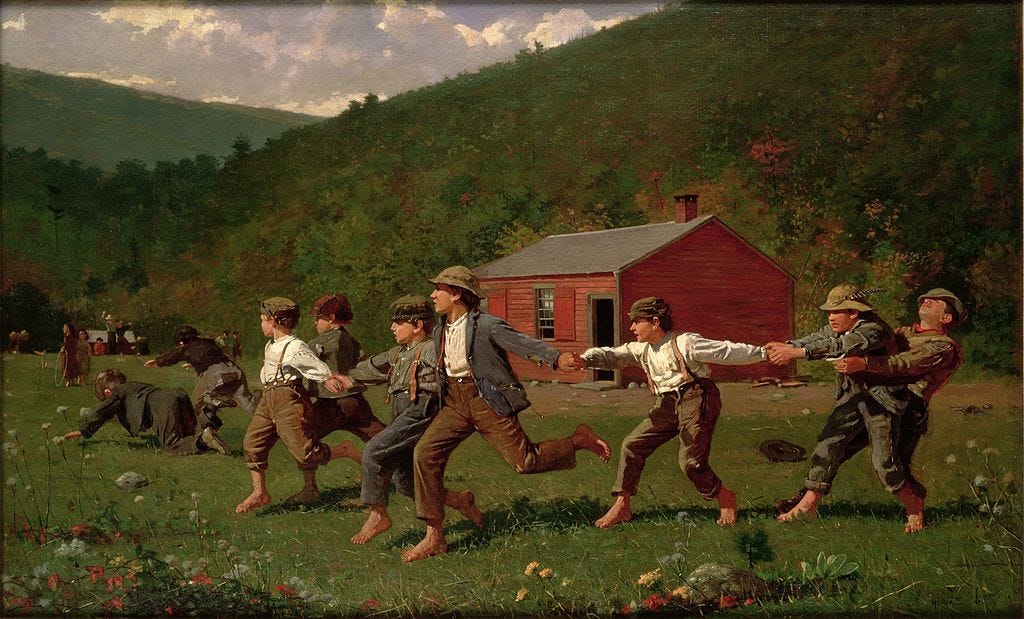

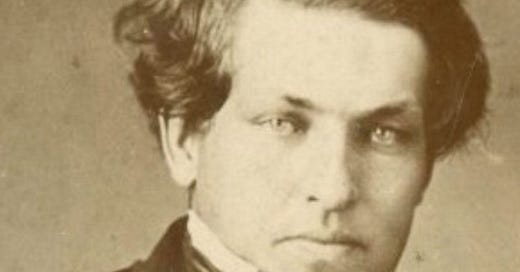

In his day, however, James Garfield was one of the most prominent men in the country, as famous for his many accomplishments as for his compelling personal story. He was a product of the frontier Midwest, his family settling the Western Reserve section of the Ohio territory. Garfield himself was born in a log cabin, the second child the bear the name James, after an older brother who had died as an infant. Garfield’s father Abram would himself die in 1833, when James was two, from the effects of trying to save the family home from a wildfire. He thus grew up fatherless and in dire poverty.

![r/MapPorn - Regions of Ohio [900x1000] [OC] r/MapPorn - Regions of Ohio [900x1000] [OC]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!4rFV!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb47a677d-ddff-4e24-a854-b87e9973d2a2_900x1000.png)

His mother Eliza was determined that her son would have a better future, and she and his older brother Thomas, both recognizing as James grew up that he was the most promising member of the family, offered to pay for him to attend school, a luxury on the frontier. She also wanted him to embrace Christianity. The Western Reserve, unlike the more culturally Southern part of Ohio which would one day shape the upbringing of J. D. Vance, was settled primarily by New Englanders, who brought with them a fervent but intellectualized congregationalist Protestantism, and academies that focused on training lay preachers were often the only educational institutions around. Garfield’s mother belonged to the Disciples of Christ, part of the Restoration Movement that had begun in her youth during the Second Great Awakening. Initially, Garfield wanted little to do with either academic or religious life, but in 1848, during a short stint as a portage worker performing dangerous and poorly paid labor, he fell into the Erie and Ohio Canal and nearly drowned. He also contracted malaria. Recovering at the family home, he reconsidered his life choices.

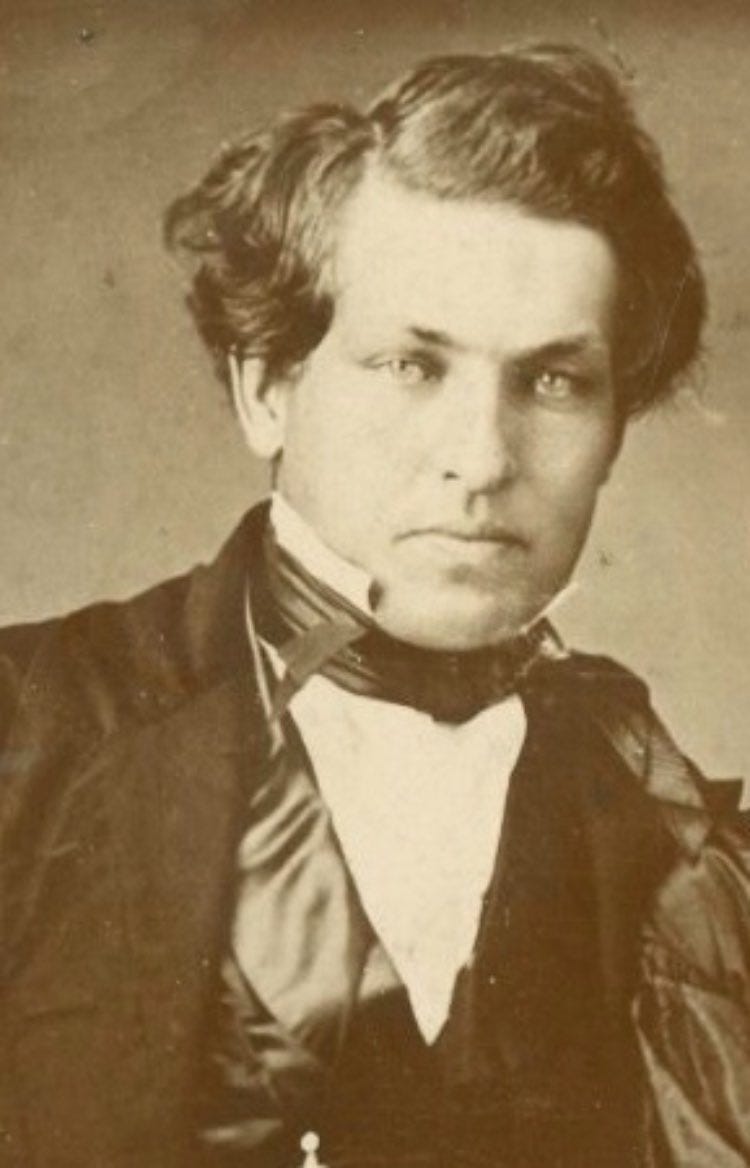

Garfield enrolled at the Geauga Academy, run by the DoC, and quickly discovered that he not only liked academic life, but thrived at it. He quickly mastered everything the school could teach him, and the school being co-ed, the tall and powerfully-built Garfield also attracted the attention of the ladies. In particular, he was fond of Lucretia Rudolph, though she was at first a bit taken aback by his energy. As it happened, Lucretia’s father had been working to found a college in the area, the Western Reserve Eclectic Academy (called ‘Eclectic’ for short, now Hiram College), which would be another school affiliated with the Disciples. Garfield wanted to attend, but still had no money, and so got hired on as the college janitor with the understanding that he could attend classes when he wasn’t sweeping the floors. He soon mastered every subject there as well, including mathematics, Latin, and Greek, the latter subject he tutored Lucretia in, while growing on her. Within a couple of years he was hired as a teacher, and then left to attend the more established Williams College back east in Massachusetts. Despite his frontier ways and once again needing to work his way through school, Garfield became the salutatorian and graduated Phi Beta Kappa before returning home. He was certainly at this point the leading classicist in Ohio and perhaps its most educated man generally, and as he was also an ordained preacher in the DoC, he was a natural to take over as president of Eclectic, especially given that the erstwhile janitor was now married to the former president’s daughter. He was 26.

It might be useful for a moment to pause and reflect on the sort of country that America once was. It would be wrong to romanticize things, and say that everyone had every chance, but Garfield got into Williams College by writing the president of the school a personal letter indicating his love of academics and promising to work hard. By way of experiment, write a letter to Maud Mandel, the current president. Tell her that you wish to attend her college, that you’re a poor white man from rural Ohio, that you love Western Civilization, and that you are willing to work as a tutor on the side to pay your tuition. Then sit by your mailbox and wait for that fat acceptance envelope- any day now.

Garfield discovered something else about himself along the way- he was popular. Despite his hard life he was a genuinely friendly young man whose natural charisma had been polished in interactions with men and women from all walks of life; frontier bargemen and eastern bluebloods all liked him. He also had astonishing rhetorical skills, now well-honed from years of preaching and campus debates, aided by a Herculean work ethic and a phenomenal memory. In addition to his scholarship, he read law and was admitted to the bar in Ohio. In short, he was a natural politician, and his tenure as president of Eclectic would serve as the base for a political career that would take him, over the next two decades, to the White House, beginning with his election to the Ohio State Senate in 1861.

Of course, there were other things happening that year that put a temporary hold on Garfield’s ambitions. The Western Reserve was probably the most fervently abolitionist area of the country when the Civil War began, a Yankee colony that felt its distinctiveness sharply against the Copperhead lower half of the state. It’s telling that so many successful Union Generals came from Ohio or had lived in the state for a substantial period, including Grant, Sherman, Sheridan, Pope, McClellan, Buell, and Custer, among others (the awesomely named Bushrod Johnson would serve as a brigadier for the Confederacy). Ohio was the third largest state by 1860 and contributed over 300,000 men to the Union War effort, and five Ohioans would go on to the Presidency following their war service. The state’s pivotal role in the Civil War also marked the last time Ohio would be meaningfully victorious in SEC territory.

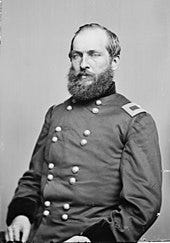

Garfield received a commission as the colonel of the 42nd Ohio Infantry, which he led into Kentucky, winning the Battle of Middle Creek. Promoted to brigadier general, he led the 20th Brigade of the Army of Ohio at Shiloh, then served as chief of staff for the Army of the Cumberland under fellow Ohioan William Rosecrans during the Tullahoma Campaign. It was in this capacity that Garfield gained national recognition. Rosecrans, suffering from the effects of exhaustion and increasingly unfit for command, fell apart at the Battle of Chickamauga, when a well-timed Confederate assault rolled up his lines and sent nearly his entire force reeling back to Chattanooga in a panic, with their commander fleeing alongside them. Garfield, on his own initiative, rode back to Snodgrass Hill, the last high ground where the Confederates could be held back from cutting off the Union retreat, and discovered that MG George Thomas, commander of the XXIV Corps, was holding in place with hastily organized forces. Garfield countermanded the order to retreat and helped Thomas hold the line by funneling whatever men he could gather to him. For this, Garfield was himself promoted to major general, but failing to receive command of the Army of the Cumberland, which went to Thomas, he instead returned to a civilian political role, taking up the seat in the House of Representatives to which he’d been elected in 1863.

Garfield was initially a Radical Republican, intent on punishing the South for the Civil War and committed to protecting the rights of black Americans, supporting the Reconstruction Amendments and military rule in the former Confederacy. His interests were broader than many of his fellow Radicals, however, and he wasn’t afraid to buck his party when he felt it right to do so. He served on the Ways and Means Committee and chaired the Appropriations Committee, which was in keeping with his interest in taxation and infrastructure. And while he moderated his more radical positions over time, especially as southern intransigence became more and more pronounced in inverse proportion to northern interest in suppressing it, his interest in reform became ever more comprehensive.

The post-Civil War period, known as the Gilded Age, was awash in corruption. Big business interests, allied to the powerful new Republican Party, bought and sold congressmen the way they did stock shares- with inflated fiat money known as Greenbacks. Garfield, watching the inept Johnson administration give way to the largely corrupt Grant administration, believed that the fundamental problem was a lack of sound money, and he advocated the retirement of the Greenbacks in favor of dollars backed with gold. He also sought to tame the spectacular growth in government the war had occasioned and the patronage system that gave enormous power to party bosses who could direct jobs and contracts to biddable supporters.

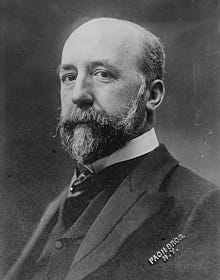

For the Republicans, no boss was more powerful than New York Senator Roscoe Conkling. Fully living up to his old-timey-Dickensian-villainy name, presiding over a vast network of loyalists in his state and beyond, all of whom were expected to kick back a share of their bloated government salaries to the big guy, Conkling was hostile to even the hint of reform. Always dressed to the hilt and possessed of an acid wit and a long and vengeful memory, he was one of the most formidable men of his age, the leader of a faction of Republicans known as the “Stalwarts” for their resistance to change. It would take someone of great character to take on Boss Conkling. Garfield didn’t hesitate.

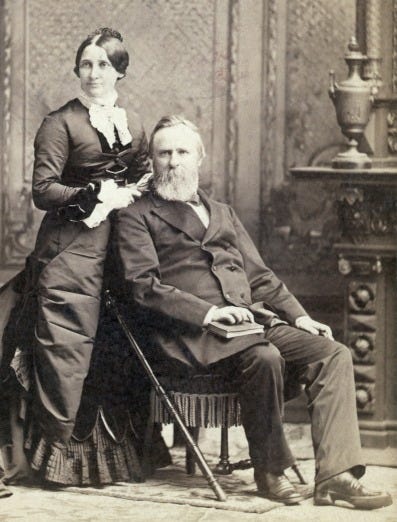

Grant, with whom Garfield had always had a frosty relationship, was succeeded in 1876 by fellow Republican, fellow Ohioan, and fellow general Rutherford B. Hayes. This election outcome was the result of massive fraud in both parties, the product of collusion in the House of Representatives between the Republicans, who had probably actually lost, and the Democrats who wanted Reconstruction to end. Hayes, while not personally corrupt, acceded to the bargain in the interest of comity, promptly declared Reconstruction a fully accomplished mission, and pulled out the federal troops just in time for Jim Crow to make his coincidental arrival. Hayes was perhaps the blandest human ever to become president, right down to his temperance movement wife, who banned liquor from the White House (‘Lemonade Lucy’ was the subtly unflattering nickname offered by alcoholic journalists), and the dirty election, his personality, and his general ineffectiveness meant that the Republicans would be looking for a new candidate in 1880.

Conkling had his ideas, and the Half-Breeds- the faction of reformers within the party- had theirs, and the party convention went back and forth for ballot after ballot. Garfield, who had committed to supporting yet another Ohioan, John Sherman (brother of William T.), was surprised to hear himself nominated, then seconded. His support grew with each new vote, Sherman accepted the shift in momentum, and Garfield was at last declared the nominee. Conkling seethed, but he realized he had a card left to play. Garfield would need to carry New York to win the election, which would be impossible without Conkling’s cooperation, and he was just the kind of person to take his ball and go home if he didn’t get his way. Knowing this, Garfield offered Conkling a plum- the vice-presidency, to a candidate of his choice. Conkling knew just the man for the job.

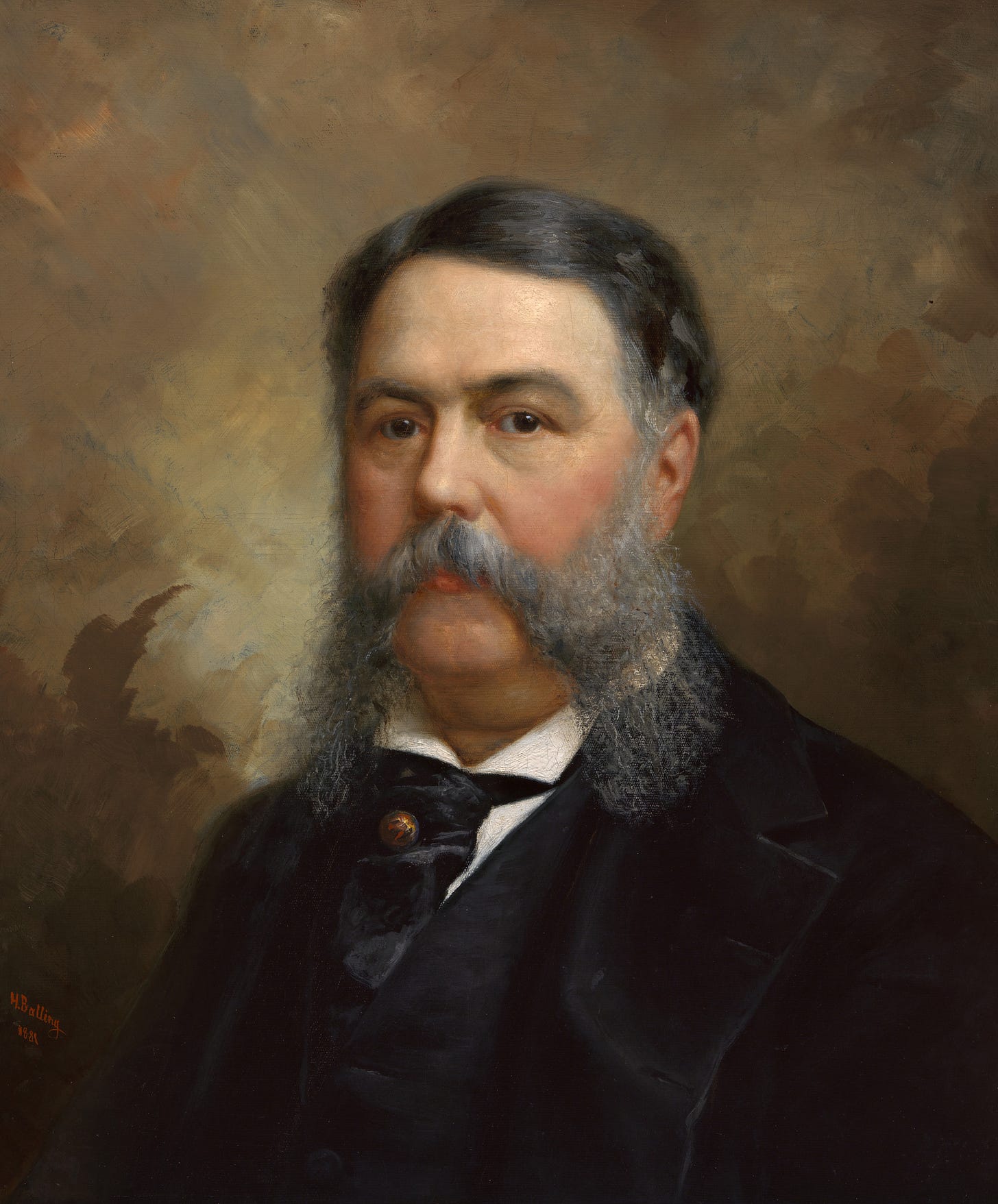

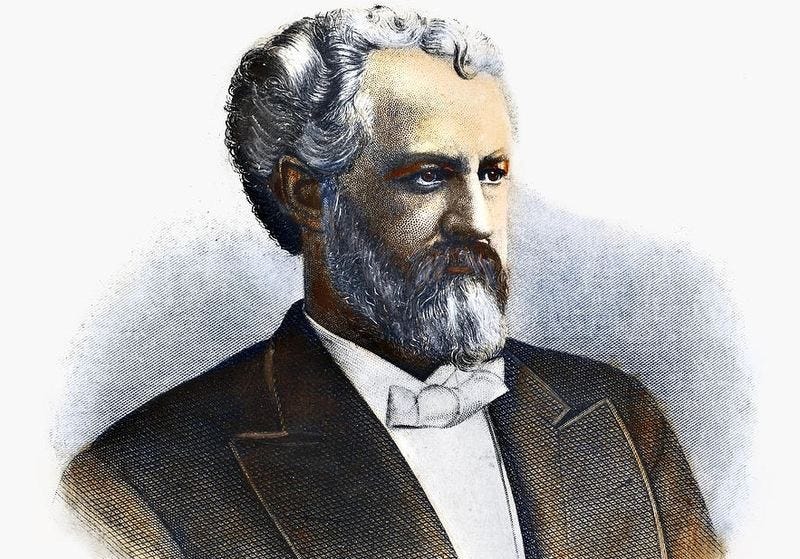

Chester Alan Arthur was born in Vermont in 1829 and grew up in upstate New York, an area culturally very similar to the Western Reserve. Arthur’s life had actually intersected with Garfield’s in odd ways; they had taught at different times at the same school, for example. Like Garfield, Arthur spend a good portion of his life as a teacher; like Garfield, he became a lawyer, and like Garfield, he served in the Union Army in the Civil War. But the similarities in their trajectories starkly illustrate the contrasts in the two men. Arthur was a bright and hardworking man, but whereas Garfield always had the aura of destiny about him, Arthur was profoundly mediocre. He got good grades, he pleased his bosses, and he earned a decent living. But for all that, he was profoundly colorless, wanting little more than a life of nice dinners, fine clothes, and respectability. Even his military service, spent as a quartermaster in New York City- also his entrée into politics- was as far from any action as he could manage, the very concept anathema to his plodding sensibilities. To the degree he was even ambitious, it was solely to the extent that he could grasp just a bit more. Even his scheming was boring.

Dull but biddable and reliable was exactly the sort of person Conkling liked, and he and Arthur quickly became the Mr. Burns and Smithers of New York politics. So unthreatening of a workhorse was Arthur that Conkling put him in charge of the New York Customs House as collector, the most important post in his gift. This enabled Conkling, by way of Arthur, to control over a thousand jobs and all the ensuing graft. It was exactly the sort of thing Garfield hated and the source of all of Conkling’s power. But if Garfield wanted to be president and accomplish anything, he needed Conkling, and Conkling needed Arthur by Garfield’s side. The deal was struck and the two men ran together to victory. It was the first election Arthur had ever stood for.

Garfield was elected to general acclaim. His mother, who’d raised him in a log cabin in the wilderness, was still alive and present to see her son become the leader of the United States, the first mother to do so. Commenters marveled that for all of America’s flaws, it spoke brilliantly of the national character than a man like Garfield, merely given the opportunity to advance, had come so far. Even more so than Lincoln, who for all the railsplitting lore was a well-paid corporate lawyer when he ascended to high office, Garfield still very much worked for a living, and the contrast between the idle princes of history and the man who spent his congressional recesses clearing land on the farm he planned to retire upon as leader was striking.

Garfield’s first few months in office were marked by tensions between his faction and that of Conkling, as expected. He and Arthur rarely saw eye-to-eye, and the latter became increasingly frozen out of decision making. Conkling was not pleased at his lack of influence. When Garfield went so far as to replace the Conkling pick as Collector of the New York Customs House with a reformer, Conkling decided this was a bridge too far, and resigned his Senate seat, convincing his fellow senator from New York, Tom Platt, to do so as well. The idea was that he would be shortly thereafter reelected by the New York State Assembly (as was done pre-17th Amendment) and thus rebuke Garfield with a show of defiance from one of the most important states. But as it happened, all of the political luck he’d enjoyed throughout his long and profitable career was about to be undone in a stunning undoing of his hubris.

For no one suspected the darkness lurking in the heart of a miserable creature named Charles Guiteau. Also from upstate New York, Guiteau was a lifelong delusional failure, who’d most recently been kicked out of John Humphrey Noyes’ sex cult in Oneida for being too weird. Wandering from town to town, dodging creditors and taking on new debts for increasingly unhinged schemes, Guiteau somehow became convinced that a speech he’d given was the reason Garfield had been elected, and that the new president owed him an ambassadorship, preferably Paris. When his repeated trips to the White House failed to result in his expected appointment, Guiteau concluded that he’d misread the situation, and decided that God wanted him to kill Garfield so that Arthur could take over, the Stalwarts being instruments of the divine.

He followed Garfield around; in those days presidents neither had nor wanted much in the way of protection, and almost shot Garfield in church. But reading that the president was scheduled to take a trip on a train, he followed him to the station, crept up behind him, and shot Garfield in the back. Garfield fell, wounded but still conscious, and his entreaties were the only thing keeping the crowd from lynching Guiteau on the spot. Interestingly, the president had been accompanied to the station by Robert Todd Lincoln, his Secretary of War and the son of the former president. Robert had been at his father’s deathbed and would also be present at the Pan-American Exposition where President William McKinley (another Ohio Civil War veteran) was shot by an assassin. His was not a life clouded by good luck.

The nation was in shock, and what followed was a slow-moving storm of darkness. Garfield probably would have recovered were it not for the incompetence of his doctors, who rejected modern methods of sanitation in favor of repeatedly probing the wound with unwashed fingers. Garfield, a man of 49 who’d amused his college-age sons by doing backflips off a bed the day before he’d been shot, lost nearly half his body weight during the agonizing weeks it took for him to die, painfully, of wholly unnecessary infection. Guiteau’s lawyer attempted to argue that the late president had technically died of medical malpractice rather than his client’s gunshot; he was unsuccessful and his client went quickly to the gallows.

The tragedy of what befell a dashing and beloved young leader with nothing but promise was compounded by the fact that the new president was nothing like his predecessor. And no one recognized that more clearly than Chester Arthur. Upon discovering that he was now in charge, Arthur broke down in tears, wholly overwhelmed by the scope of the job he now had, which everyone, including himself, believed he was totally unfit for at all. Arthur’s misfortune was compounded by early rumors (completely without merit) that he and Conkling had been involved in the murder. And there was the fact that, for all his love of creature comforts, he was a fundamentally lonely man. Conkling wasn’t really a friend, after all, his children were grown, and his beloved wife, whom he’d neglected for his political ambitions, whose only wish had been to spend time with him, had died the same year he’d been elected vice-president. Searching his soul, he was filled with terror and regret in equal measure, for the first time forced to reflect on the sort of man he was.

In the midst of this, he looked to his correspondence for hope. One letter, written while Garfield still lived, came from a woman named Julia Sand, who lived in Brooklyn. It began:

The hours of Garfield's life are numbered--before this meets your eye, you may be President. The people are bowed in grief; but--do you realize it?--not so much because he is dying, as because you are his successor. What President ever entered office under circumstances so sad! The day he was shot, the thought rose in a thousand minds that you might be the instigator of the foul act. Is not that a humiliation which cuts deeper than any bullet can pierce? Your best friends said: "Arthur must resign--he cannot accept office, with such a suspicion resting upon him." And now your kindest opponents say: "Arthur will try to do right"--adding gloomily--"He won't succeed, though--making a man President cannot change him."

Not the most uplifting message, and only a man as beaten down as Arthur would have continued to read. But it was well that he did so.

But making a man President can change him! At a time like this, if anything can, that can. Great emergencies awaken generous traits which have lain dormant half a life. If there is a spark of true nobility in you, now is the occasion to let it shine. Faith in your better nature forces me to write to you--but not to beg you to resign. Do what is more difficult and more brave. Reform! It is not the proof of highest goodness never to have done wrong--but it is a proof of it, sometime in one's career, to pause and ponder, to recognize the evil, to turn resolutely against it and devote the remainder of ones life to that only which is pure and exalted. Such revolutions of the soul are not common. No step towards them is easy. In the humdrum drift of daily life, they are impossible. But once in a while there comes a crisis which renders miracles feasible.

Julia Sand didn’t know Arthur. But something about him, something no one else saw, made her believe in him, and in the power of tragedy to change a man.

Your past--you know best what it has been. You have lived for worldly things. Fairly or unfairly, you have won them. You are rich, powerful--tomorrow, perhaps, you will be President. And what is it all worth? Are you peaceful--are you happy? What if a few days hence the hand of the next unsatisfied ruffian should lay you low, and you should drag through months of weary suffering, in the White House, knowing that all over the land not a prayer was uttered in your behalf, not a tear shed, that the great American people was glad to be rid of you--would not worldly honors seem rather empty then?

Make such things impossible. Rise to the emergency. Disappoint our fears. Force the nation to have faith in you. Show from the first that you have none but the purest aims. It may be difficult at once to inspire confidence, but persevere. In time--when you have given reason for it--the country will love and trust you. If any man says, "With Arthur for President, Civil Service Reform is doomed," prove that Arthur can be its firmest champion.

Arthur was, by his own telling, deeply moved by these words. He steeled himself for what was to come. He stood before a nation reeling from a senseless loss and took the reigns of power firmly, adding to his oath of office, for the first time, the words, “so help me God.” And he became president, not the one the nation fearfully expected, but the one it deserved.

Arthur publicly broke with Conkling. He signed civil service reform into law, ending the patronage system as it had been. He rebuilt the Navy, signed important immigration restrictions into law, balanced the budget, and most importantly, presided over an administration that, for the first time in decades, was not plagued by corruption. To the general astonishment of the public, Arthur, the face of the Spoils System, was the most honest man in Washington.

He met Julia Sands in person only once, visiting her in her home. It turned out that she was the daughter of a German immigrant, an invalid and a shut-in, invisible to the world. She was a woman who would have passed her life in total obscurity had she not felt the duty to reach out to a broken and reviled man at his lowest point, a man she’d never met, not to pile on, but to offer him hope. They would trade letters for the rest of Arthur’s life.

Sadly, it would not be a long one. Arthur began showing signs of Bright’s Disease early in his presidency, and he realized that he would not be able to serve a full term of his own. Bowing out of power gracefully, Arthur watched the Republicans lose in 1884 to Democrat candidate and fellow New Yorker Grover Cleveland, in large part due to the Republicans running James Blaine, who’d spent his career neck-deep in the sort of culture that Arthur had rejected. Conkling’s machine no longer held the power it once did, and the old boss himself never regained his former power. Arthur returned to his old law firm as a consultant, and lived quietly until his death in 1886 at the age of 57. Journalist Alexander McClure said of him:

No man ever entered the Presidency so profoundly and widely distrusted, and no one ever retired … more generally respected.

Julia Sand would live until 1933, dying in her home at the age of 83, with few ever realizing the impact she’d had on her country.

A man can change. He can change over the course of a lifetime, rising from obscurity through hard work and courage. He can change in a moment, throwing away his old self and becoming who he was always meant to be, the man his people need him to be. And no one, no matter how alone or how put upon by life, is beneath making a difference. The impact you can have is immeasurable. The life you save might be your own.

I'm left once again hoping that my children get a history teacher like you one day, and hoping that the leaders of our time have some Julia Sands in their lives.

Superbly researched and written, Librarian! An absolute pleasure to read, and un-put-downable.