Reading

’s recent post on Bushido I was inspired to dig around in my library for some works on the topic, in the course of which I happened to notice that today (April 7) marks the anniversary of the sinking of the battleship Yamato. As bushido- or at least the WWII Japanese regime’s understanding of it- plays a large role in that story, I thought others might find a recounting of its demise useful, given that the episode has become somewhat obscure in the West. This is a shame, as the tale not only has much to say about honor, but also the ways in which disasters become inevitable through the morbid inertia of men rationalizing their own destruction. The story of the Yamato also has an interesting afterlife, one which influenced me and I suspect many others of my generation.The IJN Yamato was the largest battleship ever put to sea, the archetype of a class of warship that was to include two sisters, the Musashi and the Shinano (though the latter was converted to an aircraft carrier midway through being built). First laid down in 1937 and completed beginning in 1940, the battleships were built under conditions of great secrecy, with the Japanese government going so far as to build giant screens to prevent the people of the port city of Kure from seeing the leviathans being constructed in the naval yard. The ships all displaced over 70,000 tons and the Yamato and Musashi mounted three main triple turrets of 79 foot-long 18.1 inch guns that could launch shells the size of Toyota Camries (Camrys?) up to the distance of a marathon. This was on top of dozens upon dozens of smaller artillery pieces that of themselves dwarfed the armament of lesser ships. Sixteen inches of steel armor and other protective measures ensured that the ships could survive over twenty torpedo hits and still fight.

They weren’t simply big for the sake of bigness, although obviously there were considerations of national pride. Rather, the ships were a key element in the IJN’s pre-war doctrine of Kantai Kessen (decisive battle), the idea being to beat the prospective American enemy by luring them into a single, huge battle and crushing them in one fell swoop, negating the American 10-1 industrial advantage and prospect of attritional warfare Japan was bound to lose. And since they couldn’t build more ships than the Americans could, they would make them bigger and deadlier. It was thought that ships like the Yamato could take on three similar American vessels, and so on down in rating. The US would simply be outclassed.

This doctrine owed much to the imagination of men who were junior officers during the heady days of the Battle of Tsushima in 1905, where just such a theory was demonstrated to great practical effect when Japan annihilated the Russian Navy. However, this victory was long before air power had made itself the decisive factor in naval warfare, and while battleships and long guns had their place in WWII battles, they were by no longer the most important ships afloat and, crucially, were now unable to defend themselves without their own air cover, no matter how well equipped and armored they were. Isoroku Yamamoto, one of the few flag officers with any imagination in the IJN, had done his best to make the carrier the central element of naval doctrine, with mixed results.

On one level the Japanese understood the importance of air power and put great effort into finding only the best pilots for naval aviation. Pearl Harbor had demonstrated what they could do when used creatively. But still, the notion lingered among high command that that sort of thing was not how ‘real’ naval battles were won, and that when the time came the Americans would be ultimately crushed the way Togo had crushed the Tsar’s armada, as the deified Alfred Thayer Mahan had taught. It was the same mindset that lay at the root of the fleet’s unwillingness to embrace the potential of the submarine or provide adequate protection for the vital merchant ships that kept the war effort going. Naval warfare meant ships with big guns shooting other ships with big guns. Anything else was ancillary.

By 1945 the results of this line of thinking were plain to see. Japan had lost a series of important engagements, most recently the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October of 1944, the largest naval battle in history, that saw the Musashi sent to the bottom along with most of the rest of the surface fleet, nearly all at the hands of torpedo planes and dive bombers, scarcely having brought their guns to bear on enemy ships. The Musashi had been sunk by some thirty-six torpedo and bomb hits from Helldivers, Avengers, and Hellcats launched from American carriers, with what little Japanese air power remained helpless to fight them off. It was a one-sided slaughter.

But all this has been foreseen. Operation Sho-1, the counterattack against the Americans landing in the Philippines by the Japanese surface fleet, wasn’t really meant to succeed. It was a naval suicide mission, a gesture of defiance on the part of a doomed warband against a superior enemy. At least, that was the perspective of high command, from behind their desks at IJN HQ. For the command officers of the surface fleet, the prospect of sacrificing their ships and men so that neither would face the shame of being unscathed at war’s end was not as popular a notion as Westerners might think. As Ian Toll notes in Twilight of the Gods, part three of his magisterial history of the naval war in the pacific:

In truth, the officers and men who manned the Japanese fleet had never really bought into Plan Sho, because it did not offer a realistic prospect of success. They understood that the staff officers who had written the plan did not really expect them to win, but to fight one last glorious battle to crown the Japanese navy’s career. They were being asked to offer up the still-mighty Combined Fleet as a sacrificial lamb. But the Japanese navy differed from the army in this respect: its culture, training, and traditions offered no precedent for a mindless, headlong banzai charge. While the naval air corps was eventually given over to kamikaze tactics, that development was a last resort, long delayed by opposition in the ranks. It involved sacrificing airplanes and novice pilots who lacked the skills to fly and fight using conventional tactics. But the emperor’s ships were major capital assets, state-of-the-art weapons, beloved national icons, built and manned over many decades at monumental expense. It had never been intended that they should immolate themselves for the sake of abstract considerations of honor. Throughout its history, the Japanese navy had always tried to win. Winning was its prime objective: “dying well” was an ancillary virtue. If a ship’s fate was to be destroyed in battle, she was expected to go down with guns blazing. If a man’s fate was to die in battle, he was expected to die willingly, and afterward his spirit would rest eternally at Yasukuni Shrine. But the overriding purpose had always been victory. Now, in October 1944, the ironically named “Plan Victory” inverted that order of priorities. The Tokyo admirals had foreseen that if the Americans gained possession of the Philippines, the fuel supply problem would become impossible to solve. In that case, the fleet would be immobilized, left to end the war while riding at anchor, or to sink in port under a rain of enemy bombs. Sho’s driving purpose was to avoid that ignominious finale, to ensure that the Japanese navy went out with a bang rather than a whimper. If it was possible to win, so much the better, but the battle must be fought no matter how long the odds.

And

Pacific War histories have tended to underplay the controversy created in Japan, and even in the military ranks, by the introduction of organized suicide tactics. Many Japanese resisted strongly, arguing that it misconstrued traditional samurai warrior ideals (bushido). Some naval officers associated the concept with a pathological “death cult” that held sway in the Japanese army, and they argued that it had no place in the navy.

He refers here specifically to kamikaze attacks, but the broader point stands that many senior officers in the IJN thought pointless sacrifice less noble than malignant, especially given that those urging on said sacrifice often did so from afar. Notably, those same kamikaze tactics were first deployed at Leyte Gulf alongside the destruction of the Musashi and her escort fleet. This was less traditional bushido and more fascistic war-fetishism. More Toll:

… bushido had always been an elite, class-bound creed, and was not necessarily suited to mass adoption across the population. In the transition, it underwent subtle but significant distortions. The ancient bushido of the sword-bearing samurai had emphasized zealous loyalty to a local feudal lord—but not to the emperor, who had been an obscure and little-thought-of figure before the Meiji era. Bushido meant stoicism, self-discipline, and dignity in one’s personal bearing; it emphasized mastery of the martial arts through long training and practice; it lauded sacrifice in service to duty, without the slightest fear of death; it demanded asceticism and simplicity in daily life, without regard to comforts, appetites, or luxuries. The samurai was “to live as if already dead,” an outlook consonant with Buddhism; he was to regard death with fatalistic indifference, rather than cling to a life that was essentially illusory. Shame or dishonor might require suicide as atonement—and when a samurai killed himself, he did so by carving out his own viscera with a short steel blade. But traditional bushido had not imposed an obligation to abhor retreat or surrender even when a battle had turned hopeless, and the old-time samurai who had done his duty in a losing cause could lay down his arms with honor intact.

Still, despite doubts, no one refused orders or resigned their commissions over what amounted to a demand for suicide and the immolation of thousands of young men for no real gain. Institutional imperatives were too strong. Everyone knew there was something horribly wrong with what they were doing but everyone also faced the censure of their comrades were they to act upon that truth, so they all simply continued to die and to command others to die in service to lies propped up by the sacrifice of others. It is an excellent illustration of the principle that physical and moral courage are not the same thing and the basic framework for how the Japanese architects of the disaster that was the Pacific War (and the war in China for that matter) rationalized their decisions and actions.

The Shinano never even got the chance to been sent off to die needlessly. The giant aircraft carrier was sunk in Japanese home waters by a submarine captain getting the shot of a lifetime against a ship his commanders at first refused to believe even existed. This left but one sister with one possible fate in one possible place. The Yamato’s turn had come.

By late March, 1945, the Americans had at last come to Okinawa, to the sacred territory of Japan itself. While it was true the island was largely inhabited by a despised indigenous race who’d famously invented karate to fight off Japanese imperialism, the Japanese ruling junta meant to defend it with every life available to spend. Willing as they were- ultimately and pointlessly- to annihilate some 110,000 military personnel and a like number of hapless civilians, they wouldn’t very well let the Yamato sit the fight out at anchor in its home port. With the Americans pressing in from their beachheads, command sent word to fuel up for a very important mission.

Operation Ten-Go was to be a multi-service combined arms attack, set to go on April 6, 1945. The Japanese Army would attack in full force at every point along the American lines, while kamikazes of both the Army and Navy hurled themselves at enemy ships. While this was happening, all remaining surface ships in the IJN would flank attack the American fleet with everything they had. Since the Japanese had no way to refuel their smaller ships, much less the monster Yamato, the former were expected to fight until being destroyed, while the latter was to attempt to beach itself and fire its guns until its ammunition was exhausted. Something something something- victory!

To his credit, the commander of Second Fleet (the IJN’s surface ships), Seiichi Ito, told the representatives of Admiral Soemu Toyoda, Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet, that his plan was asinine and that he thought it was a pointless waste of lives and resources, all to no avail. The other officers of the Second Fleet concurred to a man. But high command was unmoved. Everyone knew the war was lost and everyone also knew they had to believe they were one great stroke of war from winning. The Yamato was both key to that imagined victory and too great a symbol to be given over as spoils to the enemy. The emperor himself had demanded it, or so they told the officers and men of Second Fleet. The two-track logic of rationalization demanded that it fight.

Vice Admiral Seiichi Ito

Toll again:

The officers and crew of the Yamato and her nine escorts held no illusions. Their mission was a naval banzai charge, a futile suicide rush that served no real tactical purpose. Without air cover, they would be left to fight off waves of American planes with their antiaircraft guns alone. Just as in the earlier case of Sho, the Japanese “victory” plan for the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the fleet was being asked to immolate itself for abstract considerations of honor. Unlike in the earlier battle, however, there was not the slightest hope of surprising the U.S. fleet. One senior officer remarked that it was “not even a kamikaze mission, for that implies the chance of chalking up a worthy target.”

And so, the Yamato departed the port of Tokuyama on April 5th. All officers and crew had been fully briefed on the actual nature of their mission and had been given the chance to stay behind voluntarily. None did so. Recent graduates from the Etajima Naval Academy, mere teenagers, were ordered off the ship, as were the sick, injured, and those who very recently arrived. Both pride and mercy played a role in this; the Yamato was the flagship of the Japanese Navy and its veteran crew was composed of hand-picked men down to the lowest ranks. Now was no time for anyone new or anyone who couldn’t fight to the fullest. That night, as the ship sailed to meet up with the other nine vessels that would participate in the attack- a single light cruiser and eight destroyers- the crew of the Yamato held a wild party. The captain of the ship ordered the commissary to distribute stores free of charge, and made the sake that was normally locked away available to all. The sailors drank and sang songs and hugged and fought each other, all with unrestrained wildness and with no regard for rank. Perhaps some even prayed.

Of course, there was no way to hide their mission, even if the Americans hadn’t cracked their communications codes and been tracking the whole operation from the moment of its conception. The US Navy had full air supremacy, with the Japanese able to muster a mere 115 planes from land bases, nearly all of whom were meant to serve as kamikazes rather than air defense. In addition, American submarines intercepted the fleet as it made its way south and shadowed it, forwarding news of its progress to the carriers further ahead. Everyone knew where they would be and when they would get there, and prepared accordingly.

At around 12:30 on April 7th, just as the Second Fleet entered open water and assumed defensive formations, the carrier planes of Marc Mitscher’s Task Force 58 appeared overhead, nearly four-hundred strong. The fighters came in first, the massive Hellcats and temperamental Corsairs beloved only by marines, but realizing that there were no Japanese planes to clear from the skies, they made way for the ship-killers. These were the Helldivers and Avengers, dive and torpedo bombers respectively. With time on their side they circled like lions around a tired old buffalo, carefully working out the tactics they would use. The fighters would swoop in first, launching their 5-inch rockets and strafing the decks with incendiary bullets, which would create an opening for the dive bombers to come in from above in their 80 degree, terminal velocity descents in order to drop their 500 and 1,000 pound explosive payloads. Both of these attacks would keep the AA focused upward while the torpedo planes launched their own high-speed wavetop-level attacks, all on the port side of the ship to maximize the chances of forcing the Yamato to founder.

The Yamato was surprisingly agile for a ship its size (one American pilot said it was like seeing the Empire State Building floating in the water) and dodged most of the initial wave of bombs while filling the sky with AA fire and shells from its massive guns. The great “beehive” explosives fired from its main batteries could theoretically wipe out a whole squadron with shrapnel. But the fire was largely inaccurate; even at this stage in the war the training for battleship crews mostly focused on shooting other ships. Technology the Americans had been using for years at this point, like radar-assisted fire control, was absent from the Yamato. Thus, the biggest danger to the Americans was crashing into one another.

The Yamato could not dodge forever, and the American pilots gradually tightened the noose as several destroyers around the big ship were sunk or taken out of action. The Yamato was hit with four bombs in quick succession; a strafing run then silenced more of the AA batteries. Then the torpedoes began striking, four on the port side all at once. The other ships in the flotilla were being punished as well. The light cruiser fighting alongside the Yamato, the Yahagi, was pounded into a flaming wreck, as was the destroyer that tried to evacuate its crew. More strafing runs followed. The captain of the Yamato, Kosaku Aruga, ordered counterflooding to stop a dangerous list. The ship now had a deeper draft and a slower speed.

The first wave of American planes retired back to their carriers as a second came in, freshly loaded with bombs, ammunition, and advice from their departing colleagues. The Yamato absorbed at least five more torpedoes and another that took out its rudder, leaving it unable to steer. Most of the topside was either on fire or shredded by massive bombs. Communication with different parts of the ship became nearly impossible. The ship listed dangerously. It was at this point that Captain Aruga, to prevent the ship from foundering, ordered the starboard engine room flooded, which he knew would drown the hundreds of men working there. This corrected the list for a time but now the ship could barely creep forward. And yet another wave of Americans had come.

More bombs fell and more torpedoes struck. The Yamato began to list again and this time there was nothing to be done. The underside of the ship, unarmored, was now practically at the waterline, and the Avengers were not slow in attacking there. Power was totally lost. Admiral Ito, commander of this doomed mission, politely shook hands with the staff of the ship and retired to his cabin, where he remains to this day. Captain Aruga tied himself to the binacle (the brass stand with the navigation instruments); others among the few survivors recalled seeing officers bound to the flagstaff or even one another.

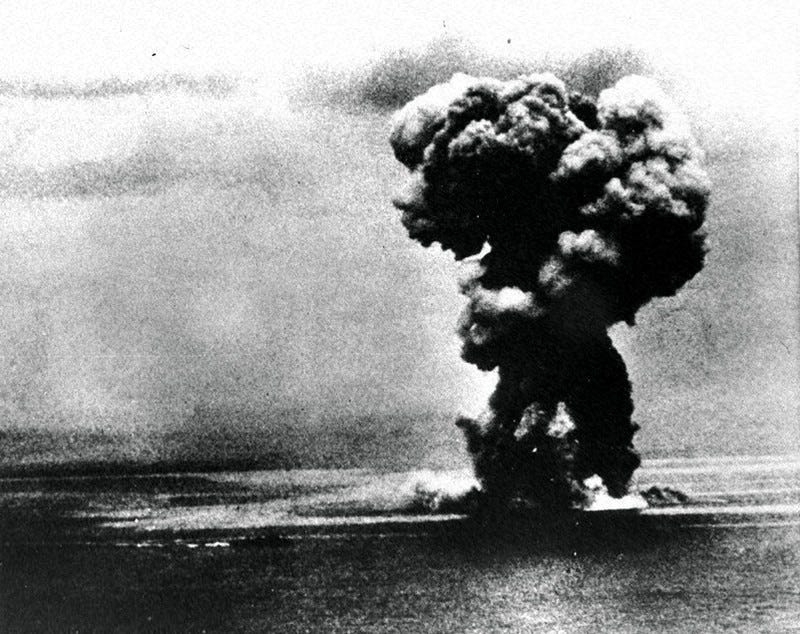

Slowly the ship began to slip beneath the waves, as those who could dove into the oil-covered flaming water to try to escape. The sinking ship created suction that pulled men under, spit them back out, and then under again. The final end to the Yamato was suitably dramatic; the main magazine exploded, sending a mushroom cloud a thousand feet in diameter 20,000 feet into the sky, which was seen over a hundred miles away. Many of the ten airplanes the Americans lost that day were actually taken out by this single giant blast. For their part, around only two-dozen officers and 250 men survived the sinking of the Yamato, with nearly 3,000 others sent to a watery grave, having achieved nothing beyond dying in a fashion the men above them deemed appropriate.

Was it bushido? Even the men involved refused to call it honorable. Captain Hara of the Yahagi had said the attack amounted to throwing an egg at a rock, and that the men sent to die a helpless death at sea could have been better used defending the homeland. It is true, as the Hagakure notes, that the way of the samurai is the way of death, but this is meant to be understood as mindfulness of death, freeing one to live a life of virtue. Likewise, the Bushido Shoshinsu of Taira Shigesuke advocates this same spirit of memento mori so that one might live a long and peaceful life. The Life-Giving Sword of Yagyu Munenori offers the paradox that the death demanded of a warrior is life for others, and that mindless- and pointless- violence is anathema to the samurai way.

The men who ordered the Yamato on its final voyage were wholly alien to this spirit. Like their counterparts the Nazis and fascists, and like many today who seek a “warrior code” of fetishized violence unmediated by moral considerations or any purpose beyond the imposition of the will on others, they distorted authentic teachings that would sit well alongside the best of pagan Greece and Rome into a bastardized modernism that sublimated man’s true high purpose to the political ends of a weaponized personal inadequacy. The archetype of this in the West is Himmler, a man who ordered the deaths of millions while scarcely capable of violence himself; his eastern counterpart is Tojo, sending millions of young men to pointless deaths, but himself ending up in a American noose rather than taking his own life as he himself valorized (yes he did try; no, he was not serious- he knew where his heart was, and in any case, where was his wakizashi?). In both instances they ruled with pens and viewed their own people as little more than abstractions, so much mass used to inflict their own dreams of glory as filtered through their giving of themselves over to some -ism or another. They and those like them, neocons and woke apparatchiks and sundry others, are the excrescence of the Enlightenment in their belief that the world can be arranged by man to some end dreamed up by a philosopher, rather than recognizing, as St. Augustine did so long ago, that no city of man endures, and only the peace and order of God is eternal.

But though the deaths of the men of the Yamato (and their peers) were pointless, they were not meaningless. They showed great courage in their final moments, and there is much more that can be said about the personal choices of many as revealed by survivors (the chief of staff for Captain Aruga literally beat younger officers to force them to abandon ship rather than die as he intended to). It is in such moments that the real character of a man is revealed. As one would expect, the Japanese remember the bravery of the men of their greatest warship, and as one might also expect, it has shown up in not just movies, but anime.

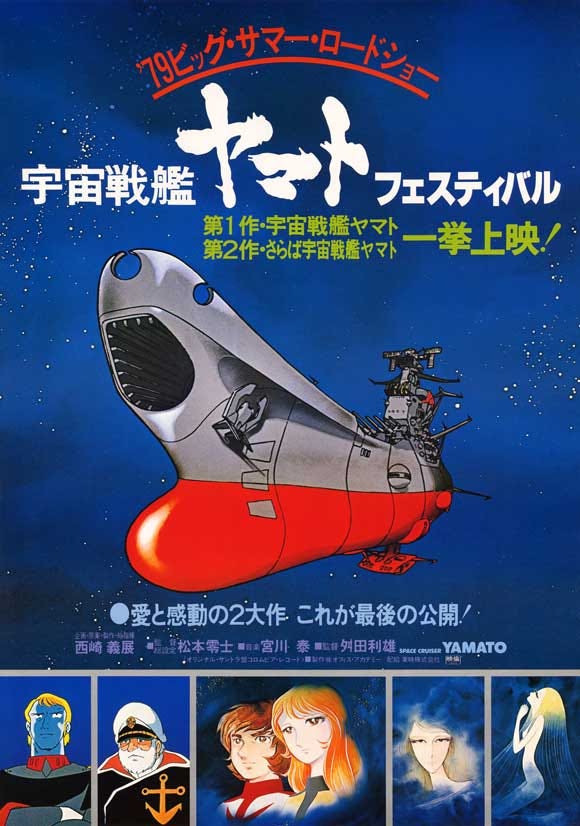

When I was a very young child I used to watch a show called Star Blazers, which debuted in 1974 as one of the first anime meant to be viewed as a serial, and in Japan known as Space Battleship Yamato. The story involved the ship being raised from the sea and fitted with an alien engine that would allow it, as the title indicates, to traverse space in order to save earth from a conquering galactic empire. All the references were lost on me as a kid and of course the US version was bowdlerized to suit 80s child audiences (it’s actually a very mature series), but in learning more about it I find the choice of the Yamato as the ship very poignant. The word Yamato itself is the title of an ancient province of Japan, but carries the secondary meanings of a poetic name for the country (like ‘Albion’ for England) and as a shorthand for the Japanese spirit. And in the show, the ship is resurrected- as though the ocean has baptized it into new life- and put to use not as an instrument of conquest but as Japan’s contribution to the liberation of Earth from a hostile empire. The heroism of the men of the ship is thus redeemed by being put to a noble purpose, one the great theorists of bushido would have recognized.

Do watch the series and the 2005 film Yamato which follows the final days of a survivor as he remembers the ship’s final hours- it’s sort of a cross between Saving Private Ryan and Titanic.

If you're still teaching in a decade, I might have to track you down to be my son's history teacher. I didn't learn anything about the Japanese Navy in school (other than the fact that they lost). These kind of story-based lessons are invaluable.

Holy shit Star Blazers! I loved that show as a kid. Wow me and my friends were into it.

Anyway, great article.

I knew about the Yamato, but not the Shinano.

WW2 is an endless well of incredible stories.

Both ships's stories are blockbuster movies if presented well. Which, as we know, Hollywood is mostly incapable of doing these days.

Watching the Shinano video above, when Captain Abe makes the fatal decision to turn south right into the stalker submarine's path, one can only smile at the familiarity of what we are witnessing. But there is of course melancholy added due to the price paid by these men. Once again, we see the timeline of human history and the results of significant events being driven by decisions that seem harmless, wise, or very unremarkable at the time. An action or decision that needed only a few seconds to complete turns out to be wrong and it reverberates for decades, and then centuries and millennia.