Collateral and the Remembrance of Death

Memento Mori Dramate

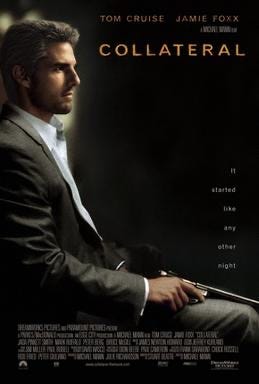

Sometimes, when I’m considering what to write next, a number of ideas for different essays coalesce into one, like different streams flowing into a single current. A number of people have written interesting things about the Los Angeles Fires, to which I had hoped to respond, and I had given a lot of thought to Billionaire Psycho’s latest on the pitfalls of writing in an absence of discipline apropos George R. R. Martin. Along the way I made a stray, joking post about Michael Mann, conflating the scientist/ vexatious litigant with the famed director of the same name. Regarding all that, I was in turn reminded of a movie I’d seen when I was younger that I always thought was a masterpiece, Collateral.

Directed by Mann and released in 2004, Collateral was one of a number of neo-noir films set in Los Angeles since the early 1990s, the first of which was The Two Jakes (1990) the sequel to 1974’s Chinatown. Neo-noir as a genre refers to films featuring themes of paranoia, alienation, vice, loneliness, and moral ambiguity, wherein the protagonists often have to make difficult ethical choices with no clear right path forward in a corrupt or indifferent world. It’s never nihilistic as such; morality does exist in the neo-noir universe, but good characters are often forced into situations where they have to do something ostensibly bad to prevent some greater evil. They generally also feature raw and realistic violence and incorporate unconventional camerawork to emphasize the fraying of mental and moral stability.

Neo-noir films are astonishingly diverse, and the genre can work in historical settings and even science fiction. A full list of neo-noir films would be book-length, but even a survey limited to films set in LA between 1990 and 2010 is sufficient to show the range and diversity of movies on offer. Curtis Hanson’s LA Confidential (1997) is perhaps the type-film, based as it was on an original work of hardboiled crime fiction like the paleo-noirs of old, and was both wildly successful and critically acclaimed. But there’s also Clive Barker’s Lord of Illusions (1995), a crime drama but with supernatural horror elements; David Lynch’s surrealist trilogy- Lost Highway (1997), Mulholland Drive (2001), and Inland Empire (2006); films that feature racial and class themes like the Hughes Brothers’ Menace II Society (1993) and Carl Franklin’s Devil in a Blue Dress (1995); and more paradigmatic movies like The Salton Sea (2002) and Hollywoodland (2006). Michael Mann’s earlier Heat (1995) also fits the bill, though some might dispute this.

The best Pacino line delivery of all time.

I single out Los Angeles because it seems to be the most popular choice of setting for the genre, whether past, present, or future (like 1982’s Blade Runner), though depending on how one defines it one could get a different result. In terms of big cities one might choose New York (King of New York, 1990), or Chicago (Thief, 1981), or even Boston (Gone Baby Gone, 2007; The Town, 2010). But there’s something about LA that lends itself to the noir imagination, or rather, something about the collective perception of the city. America is a society defined by a frontier- or was- and Los Angeles was where that moving Faustian borderland physically and metaphorically terminated. It became the liminal space through which the mythogenic West passed from memory to legend to commodified story, a place where real men like Wyatt Earp and Quanah Parker could experience a kind of living apotheosis into movie characters. It’s interesting that in addition to big cities the Old West is a popular noir setting-consider Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) and Unforgiven (1992). It would be fair to say that in the popular imagination there’s simply something unreal and insubstantial about LA, that’s it’s a hollow façade of a city, a great sprawling body with no heart, an egregore of fantastic consumerism with an appetite that feeds on dreams and vice. There are certainly natives or residents of the city that would contest this, or note for what is probably the hundredth time for them that Hollywood or the Sunset Strip are not synonymous with LA as a whole. All true, but immaterial; neo-noir Los Angeles is a fictional construct representing ideas only tangentially related to the actual living city, the real place where couples fall in love, children play on jungle gyms, and communities that are as real as those anywhere else live and struggle. The LA of the American imagination can be a battleground of contested meaning in a way that Cleveland, Ohio never could.

They’re not Detroit, so that’s something.

In that sense, Collateral is a bit of a unique LA movie. Unlike LA Confidential or so many other such films, Collateral keeps allusions to glamour or fame to an absolute minimum. Stark and spare and stripped down in its narrative, the film is a depiction of the city as a hub of homogenizing globalist modernity rather than a colorful La La land, a big place full of small people who figure into only the pieces of a greater story. Mann made the wise choice generally to forgo the palm trees, bungalows, and ethnic neighborhoods so ingrained in the general moviegoers’ imagination in favor of setting most of the scenes in the high-rise laden urban core of the city, making for something at once superficially generic yet subtly, particularly LA. The city is very much a character in the movie- in a sense it’s the main antagonist- and it wouldn’t have worked for it to have been set anywhere else.

Collateral takes place over a single night and follows only two characters throughout the entire film. The first is Max, played by Jamie Foxx, coming off a star-making, Academy Award-winning turn in earlier 2004’s Ray (he would be nominated for a second Oscar for Collateral). Before that year, Foxx had been known mainly for comedy, his serious acting limited to smaller supporting roles like in 2001’s Ali. The part of Max was a stretch for Foxx; his previous dramatic roles had been supporting bits playing real historical figures he could emulate, while Max represented a main character he would have to cultivate from his own emotional resources. And while the real-life Foxx is multitalented and enormously successful across a great range of media, Max is anything but that.

Foxx can be seen here in the underrated classic Booty Call (1997), appearing alongside a young Vivek Ramaswamy (uncredited)

When the audience first encounters him, Max is preparing for a night shift driving a cab. We see him pick up a number of customers, each serving to illustrate that his life is largely made up of transitory and transactional interactions with strangers. The tone then shifts when Annie enters the cab. Played by Jada Pinkett-Smith, she is a federal prosecutor on her way downtown, and she engages with Max concerning her big upcoming case in the morning. It cannot be stressed enough how much the film depends on scenes like this and how perfectly it pulls them off. When the two leads aren’t alone, they are moving from one encounter after another with people who enter and depart the story after brief moments, each a short but brilliant character study that economically communicates a fully lived life in a few minutes of screen time. Collateral gave a lot of great actors ideal opportunities to deliver one-off dialogues into which they could put everything they had. It’s interesting that the scriptwriter, Stuart Beatty, also wrote the first Pirates of the Caribbean movie and G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra; there’s nothing else in his oeuvre quite like Collateral.

We learn here that Max has a dream- starting his own limo company, a luxury showcase service with an elite clientele. He claims to be only driving the cab per time while he gets his business in order. Annie is impressed by his plans and his skill at his job and interpreting the character of the people he transports, and after opening up to each other a bit, he gives her a treasured photo, and she offers her phone number as he drops her off.

It’s at this point that we meet the second lead, Vincent, played by Tom Cruise. Much like Brad Pitt, Cruise doesn’t get the credit he deserves for taking on really challenging dramatic roles; in a sense, his good looks and charm work against him being taken as seriously as someone like Gary Oldman. But it’s exactly those qualities that shine here as Cruise plays very much against type as a villain- the significance of the wide smile and infectious charisma the audience expects gets very quickly subverted.

Sadly, this never led to the Collateral/ Transporter/ John Wick prequel the world deserves.

Max picks up Vincent at the airport and they engage in conversation. Their very differing views on LA come to the fore; Max calls it home, but Vincent despises it for its callous emptiness. He relates an anecdote about a man dying on the MTA and not being noticed for hours as his corpse rose the train around the city. He tells Max he’s in town for one night to close some real estate deals, and just as impressed with his skill as a driver as Annie was, offers to hire him for the duration. This is against regulations, but Max accepts at the promise of nearly twice his normal income.

However, Max quickly discovers that there’s more going on than he realized when a body comes crashing down onto the roof of his cab. Vincent is actually a hitman, and he’s been paid to kill five people over the course of the evening. Having witnessed the aftermath of his first scheduled murder, Vincent forces Max to be his accomplice and drive him to his remaining hits. With his life threatened, Max reluctantly complies.

There are a number of ways one can interpret the character of Vincent. Obviously, the film evokes comparisons with Taxi Driver due to its premise, and some have speculated that Vincent is simply a projection of Max’s inner demons. Much like the debated ending of the earlier film, wherein Travis Bickle saves the child prostitute Iris from her pimp and gains the approval of love interest Betsy, there’s a kind of manifest unrealism to a federal prosecutor giving her number to a cabbie, and in the ending (more on that to come). We also come to realize Max is a bit of an unreliable narrator, most obviously to himself. It’s revealed later in the movie that he’s been lying to his mother, claiming that his limo company is long since up and running and doing thriving business, and that he’s nursed his unrealized dream through twelve years of ‘temporary’ cab driving. Max, in reality, doesn’t even qualify as a loser as he’s never tried anything he could fail in the first place. Fearful and complacent, he wishes but never acts, content to rot rather than take a risk.

Vincent, on the other hand, is everything Max isn’t. Ruthless, cunning, decisive, and brutal, one could clearly see him as a kind of Tyler Durden to Max’s nameless Edward Norton. There’s a telling scene where the police investigating the homicides preempt the obvious audience question of why Vincent didn’t just rent a car and not involve anyone else. The lead investigator, Mark Ruffalo’s Detective Fanning, states that he’d heard of a similar case where a cab driver had been blamed for a series of seemingly random murders in another city before committing suicide. Is this Vincent’s M.O. or has Max snapped and become a copycat?

There’s also the idea that Vincent is in fact the embodiment of death itself, a modern incarnation of the Grim Reaper, making himself known for his own reasons to a random cabbie. His colors are gray and white, redolent of bones and ashes. His name could be a play on vincere, death being the ultimate conqueror. His interactions are almost solely with people dying or somehow close to death- cops investigating murders, Max’s sickly mother, and of course his own victims. No one else really seems to notice him.

Even taken at face value the character is intriguing. Vincent is a blend of Nietzschean self-assertion and fatalistic indifference to indifferent cosmic forces. He adapts to setbacks to his mission with alacrity and skill and is savagely violent when he needs to be, but has no real interest in what he does and shows no sense of purpose or accomplishment. He doesn’t know or care why he’s tasked with killing people, whether they’re good or bad, nor does he profess any wider significance to his mission. Throughout the movie, he simply and repeatedly states that it’s what he does for a living, as though it’s no more meaningful than pumping gas.

There’s a sense in which Vincent is a projection of neoliberal capitalism, a kind of counterpart to Ryan Bingham, the itinerant corporate layoff specialist from the 2001 novel Up in The Air by Substacker Walter Kirn (the film version came out in 2009 with George Clooney). The difference is that Vincent is quite literally a hatchet man and the multinationals that employ him are crime syndicates. His job is also ensuring the frictionless flow of operations by removing obstacles and redundancies, it’s just that his solutions are more direct and thorough.

Tom Cruise is, along with Keanu Reeves, probably the actor most physically committed to his roles working today. His quick draw and Mozambique Drill training for this scene impressed even the seasoned experts he worked with.

I mention Bingham because Cruise’s textured portrayal prevents Vincent from being shoved into that lazy category of movie villain- the sociopath- even though Max basically accuses him of this. He understands empathy; he’s shown to be cultured, erudite, and helpful at points. Yes, in each one of those instances it’s with the ultimate purpose of fulfilling his purposeless mission. But those traits are still ambiguous and point to the real tragedy of the character. Vincent’s rationale for his hatred of LA is that of a man who longs for human connection, understands its value, but he is incapable of it. His job prevents meaningful human relationships. His work, untethered to anything, any place, or anyone, renders him a perpetual alien, a foreigner to humanity wherever he goes. The varying stories he tells Max about his own past, brief and of dubious honesty, show him as a man whose identity has eroded to the point where he simply is his job, a cipher for an economic function, the purest adaptation possible to a system that seeks to convert people into quantifiable assets from which economic outputs can be derived. What’s scary about Vincent as a villain is that his very success in the most competitive global marketplace possible has rendered him a monster, and it’s for that very success that so many of us strive.

To illustrate this, consider one of the best scenes in the movie, where Vincent and Max go to a Jazz club, ostensibly to take a break from the killings. In reality, Vincent has brought them there to murder the owner, who’s on his list. But this only becomes clear after a genuinely friendly conversation with the owner, Daniel (frequent Mann collaborator Barry Shabaka Henley). Vincent gives Daniel a chance to escape if he can successfully answer a trivia question about Miles Davis, but despite a confident response Vincent shoots him and angrily deems his answer incorrect. Max asks if Daniel ever really had a chance, to which Vincent responds ambiguously, but one wonders if this is due less to malice than Vincent’s unspoken and unrealized frustration at the inevitability of Daniel’s death and his own need to justify it to himself. He could have made a friend, but his job makes that impossible. The man whose credo is adaptability and improvisation (characteristics of Jazz, not coincidentally) is, paradoxically, incapable of real change.

Change is what Max fears most of all, but Vincent’s appearance in his life has made his familiar stagnation impossible to sustain. Everything suddenly matters; his smallest decisions become weighted with mortal significance. A decision to call for help results in his robbery and the deaths of three men at Vincent’s hand. Vincent literally forces him to stand up to his overbearing boss, foreshadowing a more significant encounter later in the film. That scene, featuring Javier Bardem as Felix, the drug lord who hired Vincent, deserves to be watched in its entirety, as a terrified Max is left with the absolutely stark choice to adapt or die. Tellingly, he saves himself by convincingly taking on the persona of Vincent.

Fleeing the scene of the fourth murder, a chaotic nightclub bloodbath where Fanning is killed by Vincent while trying to help Max, the two men finally confront each other about their flaws and hollow lives. Max accuses Vincent of being a monster, unable to truly understand people; Vincent in turn calls Max a coward, and says that while he kills others, Max is destroying himself in a toxic miasma of cowardice and self-delusion. All night long, Vincent has held the specter of immediate death over Max’s head, but here he confronts him with the real horror that, even if he makes it through the murders, even if they had never met, Max- through his own slacker indecisiveness- has doomed himself to a miserable and meaningless life as a feckless nobody, condemned to die an old man hypnotized in front of a television, his lies to himself indistinguishable from the Hollywood sludge on the screen.

It’s that awareness of mortality in its most personal sense, not prospect of the death of his body but of the dreams that sustain him, that finally prompts him to risk everything. He guns the gas, knowing that Vincent cannot shoot him while he’s careening at high speed, then crashes anyway. The police arrive and Vincent escapes, which might have been the end of things save that Max sees Vincent’s hit list and realizes that his final target is Annie.

Watch the final sequence for yourself if you haven’t. Max finds Annie and escapes from the pursuing Vincent, ending up on the MTA. Max and Vincent shoot blindly at each other through a door; the former mortally wounding the latter. Slumping onto a plastic seat, Vincent recalls the earlier story he told Max about the dead man on the train, and in a refrain only now foregrounded in the film, plaintively wonders if anyone will notice him. I couldn’t help but be reminded of Roy Batty’s death in a different fictional Los Angeles, another killer who only realized his humanity in death.

Collateral is a bold film that prompts a great deal of reflection. At what point do the compromises we make with life become surrender? Is success in an inhuman system itself dehumanizing? Are suffering and the awareness of death necessary for meaning? The answers it offers are not easy ones.

The fires in Los Angeles took place just after I was forced by my superiors at work to give up a wonderful classroom I’d put a great deal of work into for a smaller and less favored location. It’s silly to even make the comparison between getting stuck in a new workspace to losing homes and lives, but in our selfish state of fallen pride we are given to center those experiences that impact us most directly in our complaints. But in the end, that classroom was never mine. Our homes and the things we surround ourselves with, even our very lives, will ultimately be taken from us, whatever we do and whoever we are. We are meant to aim for higher things, and the remembrance of death places that stark truth in our conscious thought better than any philosophy seminar.

Writing is important to me because that’s how I process those ideas. There are many things that take me away from that mission. I have to teach in person all day and manage numerous other jobs in turn. I began this essay last night but abandoned it in short order when I realized I was too tired from my day to make sense. I took it up again this morning, typing on my school laptop in stray and stolen moments, and I’m finishing it now on my phone while I try to put my girls to bed; I’m lying next to them on the cold floor while we listen to post-rock. Sometimes I resent the burdens that impose all these strictures, but thinking of George R. R. Martin, I have to wonder if I would really be better off with more freedom. There’s a heat created from my frictions, a desire to fight back against what the world would have me be. I have no choice but to think and write quickly, whenever the opportunity arises, with no promise of when I’ll be able to pick up again. What would I be without that urgency, that need to create born of those pressures and limitations? Would Martin’s fame and money grant me Martin’s aimless indolence?

The writers I admire most had day jobs, as I’ve noted before, and even if I don’t continue at my particular workplace I can’t imagine doing what I do without some other primary labor. I don’t really want to live from my writing, but for it. Men who work in offices lift weights not because they have some practical need to be able to move heavy things, but because they sense that we thrive only in the presence of extraneous demands that force us to confront limitations. The same barbell that tells you how strong you are is also giving you insight into your weakness; a man who can bench 500 lbs is a man too soft to lift 501. Likewise, the restrictions on my time and energy force me to focus when I have to, and essays like this are the result. If it’s good, I’ve won a small and temporary victory. If not, that merely prompts me to look within and try harder next time. Because, in the end, one day there won’t be a next time.

I’d respectfully suggest the only false note in this post is your reference to your “superiors”. They’re just administrators, bureaucrats, managers. They preside over value creators and probably create little value themselves.

They are certainly not your superiors.

It may console you to conduct research on Bach’s working conditions, in a noisy school with only a thin wall separating his family quarters from the boisterous cacophony of the students.

In those blighted and nerve-wracking conditions he not only raised a large family but composed his angelic music.

AMDG as he wrote on every masterpiece - Ad Majorum Dei Glorium

"Our homes and the things we surround ourselves with, even our very lives, will ultimately be taken from us, whatever we do and whoever we are. We are meant to aim for higher things, and the remembrance of death places that stark truth in our conscious thought better than any philosophy seminar."

To quote Mel Gibson after seeing his home destroyed in the fires: "I have been relieved of the burden of my stuff."